Dr. Charles Johnson and his Legacy of Change

When Charles Johnson, MD, wasn’t busy seeing patients during his early days on the Duke University School of Medicine faculty, he spent time walking the halls and lobbies of the hospital. He did it, as he did most things, with a purpose: to be visible, to help hasten the day when seeing a Black physician at Duke would be considered nothing out of the ordinary.

“He told me he would walk the hospital just so people would get accustomed to seeing him,” recalled his son, Charles D. Johnson, PhD, a history professor and director of the Public History Program in the Department of History at North Carolina Central University. “I think that helped people over time to see — and expect to see — an African American physician.”

The elder Johnson was a beloved physician to his patients, a role model to his colleagues, a rock for his family, a mentor to many, and an inspiration to all who knew him. Born in 1927 in rural Alabama, he came from humble beginnings and overcame daunting obstacles of race and class in the Jim Crow South. He became a fighter pilot and flew solo missions over the Soviet Union and China in the 1950s — before the Montgomery bus boycott and the Civil Rights Movement.

He went on to become the first Black faculty member at the Duke University School of Medicine. According to his son, being first was only the beginning.

He came to Duke recognizing that his role wasn’t just to be the first,” Charles D. Johnson said. “It was to be a transformation agent, helping to spearhead getting more talented African Americans at Duke and keeping them there, and serving as a role model and as a guide.”

By all accounts, he did that. But it wasn’t easy.

“I think that it’s really important that we appreciate that when he started that process, there weren’t a lot of people doing that work,” his son said. “There was resistance to that. It was very challenging early on.”

That’s where his fighter-pilot mentality came into play.

“He had the drive and the moxie and the determination to make it work,” said Eddie Hoover, the retired chair of the Department of Surgery at SUNY-Buffalo. Hoover trained under Johnson as a medical student and as a resident — Duke’s first Black resident — in the 1960s.

Johnson died on December 14, 2021, at the age of 94. His physical presence may be gone, but his legacy lives on in the Duke School of Medicine, among the individuals he mentored, and in the many who followed after him.

At his funeral, School of Medicine Dean Mary E. Klotman, MD, who was among the many physicians mentored by Johnson when she was a trainee at Duke, said, “To say he paved the way for others somehow seems to be an understatement of the impact he made. Throughout his 26 years at Duke, he was committed to diversifying the profession as an imperative to delivering the best patient care. He was a pioneer and an outstanding clinician, mentor, and leader. He improved our profession, and he made Duke a better institution.”

Humble Beginnings

Johnson was born in Acmar, Alabama. His father was a coal miner and his mother worked as a domestic worker. As a boy, Johnson watched airplanes and dreamed of becoming a pilot. As recorded in a conversation at Duke in 2004, he said to himself, “I can fly airplanes. One day I’m going to fly.”

Although none of his eight siblings finished high school — “Jim Crow pretty much chewed up the rest of his family,” said his son — Johnson finished high school, joined the U.S. Air Force, and became a fighter pilot. After his military service, he went to Howard University on the GI Bill. Originally planning to become a nuclear physicist and work in industry or a national lab, he switched his sights to a career in medicine when the chair of the physics department at Howard told him, in 1951, there were no career opportunities for a Black nuclear physicist aside from teaching.

He completed medical school at Howard, his internship at the District of Columbia General Hospital, his residency at Lincoln Hospital in Durham, North Carolina, and Duke, and a fellowship in endocrinology at Duke.

As a fellow and later a faculty member, Johnson made an indelible impression on the medical students and trainees he mentored. Ralph Snyderman, MD, who would go on to become chancellor of health affairs and dean of the medical school at Duke, remembers rounding with Johnson on one of his very first rotations as an intern at the Durham VA Hospital.

“At that time, interns were at the bottom of the pecking order, and people generally did not go out of their way to be nice to you,” said Snyderman. “Charlie stood out as an individual who was not only extremely knowledgeable but also very kind and compassionate. And that became the basis of our long relationship, one of care, trust, and mutual respect.”

Coming to Duke

In 1970, Eugene Stead, MD, the former chair of the Department of Medicine, asked Johnson to join the faculty at Duke. At the time Johnson was seeing patients at Lincoln Hospital, the hospital for Black patients in Durham. He knew that many of his patients didn’t feel welcome at Duke, so he asked each of them if they would be willing to continue to see him if he moved his practice there. When most agreed, he told Stead he would come, on one condition: if anyone at Duke ever mistreated any of his patients, he would leave and take his patients with him. Stead agreed, and the two became lifelong friends.

He picked his battles. And where it really mattered, Johnson took a stand.

When he first came to Duke, the chief of his division refused his request to see patients on the so-called private wards, where virtually everyone was white, and Stead backed up the chief. But when a delegation from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) came as part of a site visit for a grant, Johnson saw his chance. In a meeting with senior faculty and administrators, the head of the NIH delegation asked if anyone in the room was unhappy with anything in the division.

As Johnson recalled in the 2004 recording, “I said, ‘I’m very unhappy. They won’t let me rotate on the private service.’ He said, ‘You’ve got to be kidding me. I’ll see to that.’”

After that, he was allowed to see patients on the private ward.

Helping Duke Grow

Johnson frequently spoke about the need to recruit more Black students and faculty, support them once they arrived, and change the environment at Duke to become more welcoming to a diverse group of people.

Barton Haynes, MD, who chaired the Department of Medicine from 1995-2002, said, “I remember him saying to me, ‘Bart, you can recruit until you’re blue in the face, but if you don’t change the environment into which you are recruiting, [you won’t] be successful.’ Of the many, many pieces of advice he gave me as chair, that was the most important.”

Wherever there was an effort to improve conditions in the School of Medicine or in the hospital for Black students, trainees, faculty, or staff, Johnson led the charge or provided guidance. He served on innumerable committees, engaged in spirited discussions, pushed, and persuaded.

“People assume that the hospital just naturally evolved into what it is today, and that’s not the case,” his son said. “It wasn’t just my father, but it took a concerted effort and people pushing hard to bring about these changes.”

Johnson stayed involved at Duke even after his retirement. He worked with the late Brenda Armstrong, MD, who was associate dean of Medical School Admissions, to recruit, mentor, and support incoming minority students. When Snyderman became chancellor, he recruited Johnson as a consultant to advise his leadership team on increasing diversity and improving the environment for Black students, trainees, and faculty.

And Johnson provided guidance and support when Del Wigfall, MD, professor of pediatrics, sought funding to establish the Multicultural Resource Center in the School of Medicine, which opened in 2000 with Maureen Cullins as the director.

“I would talk to Dr. Johnson about his experiences and what he saw as issues for faculty of color and more specifically African American faculty at the School of Medicine,” said Cullins, who co-directs the center with Wigfall. “He was particularly prescient at a time when only a handful of people were talking about systemic barriers to progress and success.”

Although Johnson was constantly prodding the institution to be better, his son said, “He loved Duke. He loved that the standard was perfection — asymptotic, he would say, you were always working to get there. He thought a lot of himself and his ability, like a lot of physicians do, and he enjoyed being associated with that.”

Helping Individuals Grow

Johnson also inspired countless individuals by his actions and advice, and sometimes just by his presence.

Joanne A. Peebles Wilson, MD, was the fourth Black student to attend the School of Medicine. Before meeting Johnson, she knew of only one other Black doctor, and none in academia. “I just remember being introduced to him and thinking, ‘Yes. This can be done,’” said Wilson, a pioneer in her own right and now a professor of medicine in the Division of Gastroenterology at Duke.

Eugene Wright, MD, had a similar experience when he met Johnson while applying to the School of Medicine in the early 1970s. “At 21 years old, you meet someone of Dr. Johnson’s stature and hear the story of all these things he’d done, you couldn’t help but want to be like him,” said Wright.

From that day on, Johnson was a valued mentor. “Not only did he touch my life, he touched the lives of so many students,” Wright said. “He supported us however we needed it to achieve beyond our own expectations.”

The support didn’t end with graduation from medical school. When Wright opened a private practice in Fayetteville, he had trouble establishing a collegial relationship with the other physicians in town, perhaps because he was the new kid on the block, perhaps because he was Black.

“I called Dr. Johnson and said, ‘I want to fit in the medical community here. I’m not trying to take their patients, but I want to do the best for my patients. How can I navigate this?’ I wasn’t sure which way to go. I could blend in and fit in, or I could really do what I was trained to do. He said, ‘You know, Gene, if people don’t like you for who you are, they surely will not like you for who you are not. Be yourself.’ And that was it.”

Putting Patients First

When Johnson retired in 1996, he asked Wright to return to Duke and take over the care of his patients. In typical fashion, Johnson did not hand over the baton until he had personally introduced Wright to all his patients.

His clinical acumen and patient-centered approach remain legendary among his colleagues. “He was the physician to all people, of all ethnicities, all socioeconomic groups,” Wilson said.

Haynes, who interned with Johnson in 1973, said, “He had the most remarkable rapport with his patients. I learned a lot from him about how to comfort people with serious diseases.”

And his patients were famously devoted to him.

“I feel so honored to have been a patient of his,” said Linda Capers, the director of the Center for Multicultural Affairs at Duke University. “Having Dr. Johnson as my physician was an illuminating experience for me. He was a great listener who was empathetic to the needs of his patients. He helped me to understand the importance of access to quality health care that communities of color deserve and should get.”

Juliette Satterwhite, RN, was not only a patient of Johnson’s, but also worked alongside him as a registered nurse on the wards from 1976-80. “I was delighted to see someone of color like me,” she said. “I came from South Carolina where I didn’t see that many medical doctors of my color. I called home and told my parents all about him.”

As a patient and as a nurse, Satterwhite witnessed Johnson offering both clinical skill and personal comfort. From his first day to his last, his patients were his top priority.

“When the patients were in the hospital, very sick, and in a lot of pain or just plain scared, he had this caring attitude and a very friendly face that calmed them down,” she said. “He would say, ‘Let me help you. I can make you feel better. Work with me. It’s going to be OK.’ He was always offering hope.”

Snyderman remembers Johnson as a great physician and a trusted friend and colleague who somehow made blazing a trail look almost effortless.

“He was a pioneer, but he did it so naturally and fit in so quickly and completely that you almost weren’t aware of it,” said Snyderman. “He just made the right thing to do so glaringly obvious. It cannot always have been easy. I’m sure he carried burdens that were not apparent to anybody else, but he did that the same way he did everything: with grace, dignity, and compassion.”

Mary-Russell Roberson is a freelance writer based in Durham. Photos courtesy of Duke University Medical Center Archives and Charles Johnson’s family.

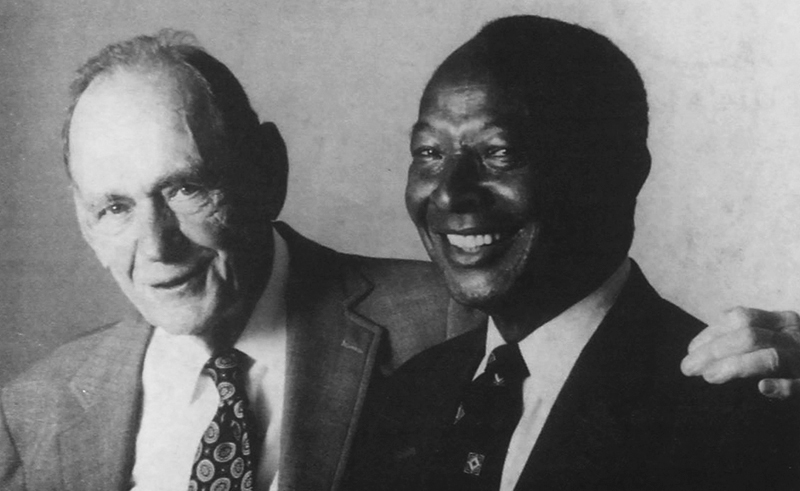

Top photo: Charles Johnson (left), Barton Haynes (center), and Eugene Wright.