When organ transplants became a more frequent procedure in the 1950s and 1960s, the standard method of transporting the organs was to pack them on ice in a cooler no fancier than what you might use to pack drinks for a picnic.

These coolers limited the travel time to keep an organ viable for transplantation — for a heart, that window was about four hours — which in turn severely limited the distance a donated organ could be retrieved and transported. Also, organs transported in cold storage could get “freezer burn,” since the temperature in the cooler was not regulated.

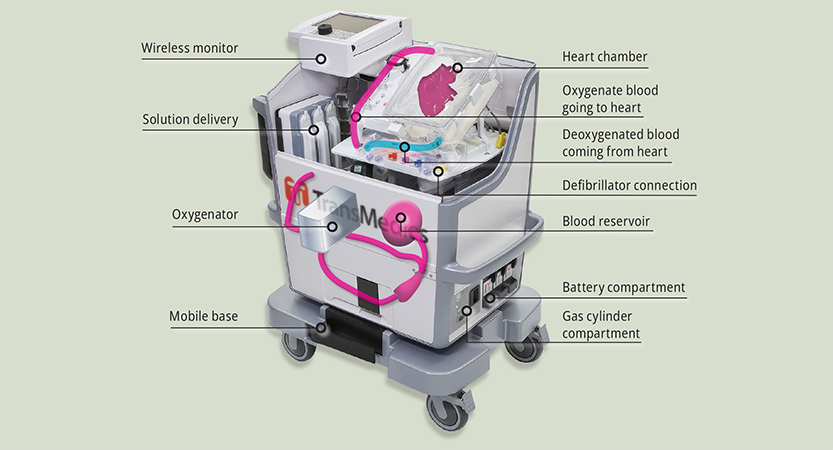

This remained the customary means of transporting organs until just a few years ago, when dramatic improvement were made in the process of transporting organs from donors to recipients. After many years of clinical trials, some of them conducted at Duke, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the use of a superior device: a battery-powered container that maintains the organ in a functioning state, perfusing it with warm, nutrient- and oxygen-rich blood, using wireless technology to monitor the organ and allow longer time for transportation. TransMedics created and received approval for the “TransMedics OCSTM (Organ Care System),” which is currently available for hearts, lungs, and livers. FDA approval was obtained separately for the Transmedics devices for each organ: lungs in 2018, heart in 2021, liver in 2022

The heart device is sometimes referred to as “heart-in-a-box,” but it isn’t really a box. It has a plastic chamber within a nearly 100-pound rolling cart that contains the donor heart, connected to tubes that pump medications, nutrients and blood through it. The heart is kept beating the entire time during transport from the donor to recipient, and its condition is continually monitored. The device contains batteries for up to 10 hours of use, but it can also be plugged into an electrical outlet. The electricity powers the oxygenator and a heater to keep the heart chamber at the correct temperature, as well as the monitoring system.

“These devices extend the life of organs once they are removed from the donor and introduce more flexibility into the system.”

-Stuart Knechtle, MD, HS'82-'89

By keeping organs in better condition for longer, warm perfusion devices enable procurement teams to travel much greater distances to retrieve organs and dramatically extend the time that donor organs can be kept viable. And by monitoring the organ during transport, the device gives surgeons a better understanding of its condition. All of this makes more organs available for transplant — a critical advance, because currently more than 100,000 people are on transplant waiting lists in the U.S., and an average of 17 people die every day waiting for a transplant.

In 2019, Duke University Hospital, as part of a clinical trial, was the first institution in the U.S. to successfully use a Transmedics device for a “DCD” — donation after circulatory death – heart transplant.

“These devices extend the life of organs once they are removed from the donor and introduce more flexibility into the system,” said Stuart Knechtle, William R. Kenan Jr. Distinguished Professor of Surgery and director of the Duke Transplant Center. “That’s a real game-changer.”

More about Duke's Organ Transplant Program

and alumni making a difference in this field:

Duke’s Organ Transplant Program: Out With the Old, In With the New

Alumni Making a Difference: David Axelrod, MD’96, MBA’96

Alumni Making a Difference: Roslyn “Roz” Bernstein Mannon, MD’85, HS’85-’90

Story originally published in DukeMed Alumni News, Summer 2023.

Read more from DukeMed Alumni News