At the Intersection of Sickle Cell Disease and Geriatrics with Charity Oyedeji

Charity Oyedeji, MD, has been living with sickle cell disease her whole life—she doesn’t have the condition herself, but many in her family do. Her brother died of the disease in infancy, and a cousin with whom she was close died at age 19. As a high school student in Houston, Oyedeji spent summers working at a camp for children with sickle cell disease.

“I’ve always had a personal interest in sickle cell disease,” she says.

Now, as a senior fellow in the Division of Hematology, she’s exploring the intersection of geriatrics and sickle cell disease. It’s a new field because in the past, most people with the disease did not reach adulthood.

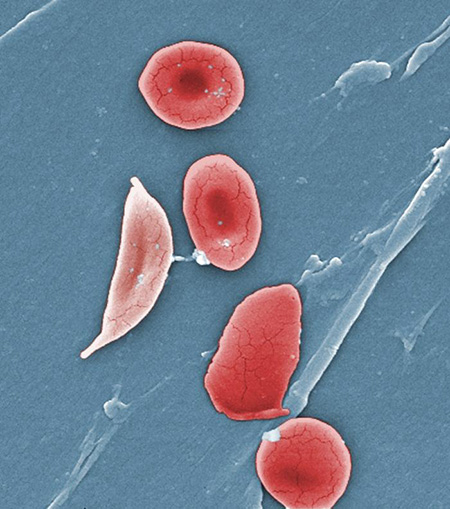

Sickle cell disease is a genetic condition in which red blood cells collapse into crescent shapes and get stuck in small blood vessels, causing excruciating pain. The misshapen cells can’t deliver oxygen efficiently, so the condition can cause long-lasting complications, including joint deterioration, pulmonary hypertension, heart failure, small to large strokes, and vision impairment due to damage to the retina or optic nerve. The sickle cell gene, which must be inherited from both parents for the disease to manifest, is more common in people with African ancestry; in the United States, 95 percent of people with sickle cell disease are African American.

Newborn screening and improvements in treatment have lengthened the average lifespan for people with sickle cell disease, with many living into middle age and beyond. That’s good news, but Oyedeji sees a problem.

“We’re getting better but we’re not where we should be,” she says. “There’s not enough attention given to aging and how the care should change.”

When she was a resident in Internal Medicine-Pediatrics at the University of Rochester, Oyedeji took care of children and adults in the outpatient sickle cell disease clinic and in the hospital. Over time, she realized, “We can’t think of [adults] the same way we thought of them at 18.” And that’s when she knew what the focus of her career would be: “I saw an opportunity to improve care for adults with sickle cell disease.”

When it came time for the next step in her career path, she chose the Duke University School of Medicine, specifically the Department of Medicine. “I knew this was a place with a lot of opportunity for mentoring in the hematology division,” she says. “And it was good that there was diversity—you want to have some mentors who look like you.”

At Duke, she approached hematologist John Strouse, MD, PhD, associate professor of medicine and pediatrics, who had completed the same Med-Peds residency in Rochester some years earlier. (“We shared a lot of snow stories,” he says. “Charity is done with snow.”)

Together they decided to focus on quantifying and addressing premature aging in people with sickle cell disease.

“They go through the wear and tear that all of us do as we get older,” Strouse says, “but we think that process is accelerated in people with sickle cell disease [due to] the effects of a lifetime of injury to the blood vessels and bones and many other organs from vaso-occlusion, inflammation, and anemia.”

In 2018, Oyedeji and Strouse received Pepper Center funding to develop a geriatric assessment for older adults with sickle cell disease and test its feasibility in a pilot study. The Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center, housed in the Duke Center of Aging and Human Development, is one of 14 centers nationwide funded by the National Institute on Aging.

“That funding created an opportunity to study an area that no one had studied,” Oyedeji says.

Strouse says, “I can’t say enough good things about the Pepper Center and the pilot projects program. It provides a way to support not just research, but also the researchers. It’s like joining a geriatric research community.”

Oyedeji agrees. “There is so much to learn from geriatricians,” she says. “They are good at [assessing physical] function and improving quality of life.”

Oyedeji studied existing geriatric and geriatric oncology assessments and consulted experts in the Division of Geriatrics, including Miriam Morey, PhD, professor of medicine; Katherine Hall, PhD, associate professor of medicine; Heather Whitson, MD, associate professor of medicine and ophthalmology; and Harvey Cohen, MD, the Walter Kempner Distinguished Professor of Medicine. She then created an assessment for sickle cell patients that included tasks and questions designed to identify impairments in physical function, strength, cognition, nutrition, social support, and psychological wellbeing. She carried out the assessment with 20 patients aged 50 and above. When it came time to do the statistical analysis, she worked with Pepper Center statisticians Carl Pieper, DPH, associate profess or biostatistics and bioinformatics, and Alison Luciano, MS, PhD, biostatistician.

Oyedeji presented the results of the pilot study in December 2019 at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology. The pilot showed that the assessment was feasible and acceptable to patients and providers. The results of the assessment itself were sobering: The 20 participants had physical function equivalent to people 20 to 30 years older, and half of them showed some level of cognitive impairment.

The implication? “We should be thinking of a 50-year-old with sickle cell disease as physically older and find and offer resources that people in their 70s or 80s are using,” she says.

With additional funding from the Duke Center for Research to Advance Health Equity (REACH Equity Center), Oyedeji also conducted qualitative interviews with the participants to understand their attitudes about advance care planning and advance directives, which African Americans use at lower rates than whites. Many participants said they would feel more comfortable discussing end-of-life issues with a trusted healthcare provider during an unrushed clinic visit, as opposed to being approached by an unfamiliar face during a stressful time in the hospital—something many had experienced.

Strouse is impressed with how Oyedeji has grown as a clinical researcher since she’s been at Duke.

“She’s done a great job of developing a very effective skill set for clinical research,” he says. “She’s gained a lot of expertise I don’t have. She’s learning things not just from a sickle cell disease hematologist, but from people who are experts on aging and physical functioning.”

He adds, “Charity is a lot of fun to work with and I think that’s one of the reasons why she’s been so successful in developing these collaborations.”

Moving forward, Oyedeji has expanded the pilot study to include a group of younger adults, aged 18-50. She is assessing each group again after 12 months, including an extra assessment for those who undergo hospitalization for a pain crisis. She wants to learn more about the trajectory of functional decline over the lifespan, and how hospitalization events affect that trajectory.

She’s continuing to improve the assessment and hopes in the near future to validate it in a multi-center study, which she is already planning. An important part of that plan is a patient advisory committee, which met for the first time last fall. “We want patients to be a part of the process,” Oyedeji says.

One of those patient advisors is Veronica Mathis, who is an intensive-care nurse in trauma surgery at Duke. Mathis, now 58, was diagnosed with sickle cell disease as a toddler, at a time when people with sickle cell disease rarely survived their teenage years. Having beaten the odds motivates her to help others with the disease. Mathis has participated in several sickle cell studies, including Oyedeji’s. “I believe in research,” she says. “If I’m going to have an opportunity to participate, I usually do. Anything that can help people, I’m for that.”

Mathis also welcomed the chance to be on the patient advisory committee, especially because she’s both a nurse and a patient. “I felt like I had something to contribute,” she says. “With my experience and my knowledge, I can’t keep it to myself. We’re here to help people.”

Of Oyedeji, Mathis says, “She listens to her patients. I find her to be knowledgeable and compassionate, which are two things you can’t get enough of as a patient, especially as a sickle cell patient and being among the population where we are known to have disparities.”

Oyedeji is intentional in listening to patients because she wants her research to make a difference in their lives. During interviews, she asks patients what their biggest concerns are. Mortality? Hospitalizations? Being able to manage pain and fatigue so they can keep working and stay off disability? Ultimately, she plans to take what she’s learned from listening, combine it with information from her geriatric assessment, and develop effective interventions to measurably improve quality of life in older adults with sickle cell disease.

One such intervention might be an exercise program modeled after the Gerofit program for older veterans developed by Morey. “Gerofit is a great model because it’s customized to individual impairments,” Oyedeji says. “Sickle cell disease is such a heterogeneous disease - some people may have hip problems, some people may have lung problems, some people may have shoulder issues.”

Strouse sees a bright future for Oyedeji—and the patients who will benefit from her research. “She’s likely to really improve the care of this group in a bunch of ways,” he says. “She’s going to help us understand their prognosis, improve their function, and improve how we communicate with them about the aging process.”

Mary-Russell Roberson is a freelance writer in Durham. She covers the geriatrics and aging beat for the Department of Medicine in the Duke University School of Medicine.