Victor Roggli: Cystic Fibrosis Survivor, Asbestos Expert, Karaoke Star

Victor Roggli, MD, has made a career out of examining what dangerous jobs and toxic environments leave behind in the human body. A leading pulmonary pathologist at Duke University School of Medicine, he has focused on the study of minute particles — dust, fibers, and especially asbestos — that lodge deep inside the lungs.

His research has shaped medical understanding, courtroom battles, and workplace safety standards nationwide.

Now in his 44th year on the job, Roggli is working in a career he was never expected to have. Diagnosed with cystic fibrosis at 7 years old, he wasn’t supposed to live past age 12 — a prognosis he quietly defied as he went on to become one of the most influential voices in occupational lung disease and the author of “Pathology of Asbestos-Associated Diseases,” a standard reference in the field.

See more in the: The Pathology Report 2025

“I really didn’t give much thought to the philosophy of taking my life to the highest potential with the full expectation that there would be a tomorrow instead of retreating to a place of safety or security that demanded nothing of me.

“Instead, I plunged ahead as if driven by an unseen force pushing me to the limits of my capabilities,” he said.

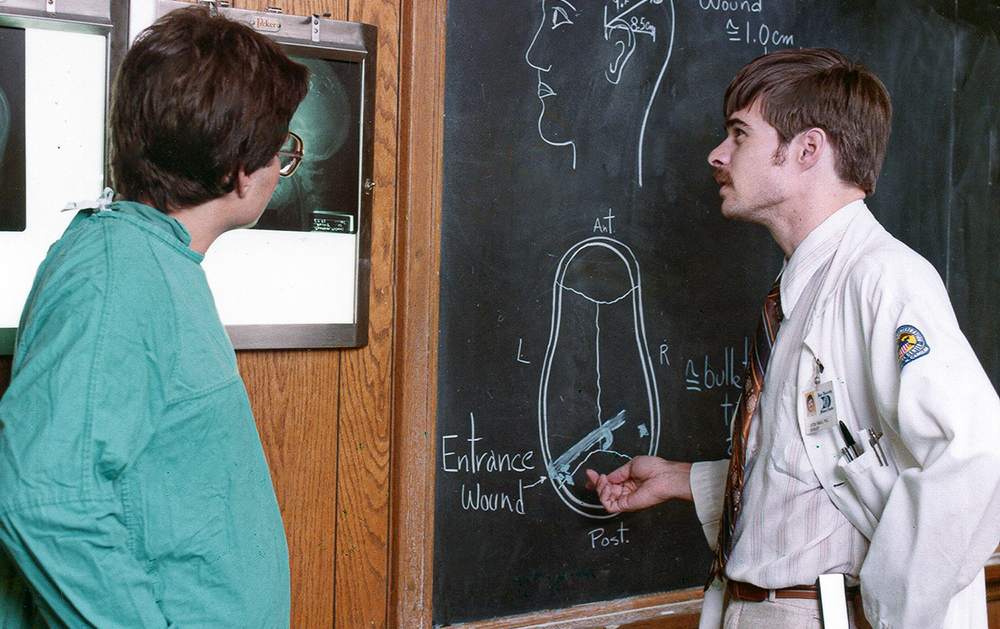

Roggli’s work extends beyond the lab. He has served as an expert witness in asbestos-related trials, helping juries understand how microscopic fibers can cause cancers that appear decades after exposure. His testimony often bridges the gap between medical science and the stories of workers in shipyards, factories, and construction sites.

A career built on invisible hazards

Roggli grew up on a farm in Cowan, Tenn. He spent his early years attached to a heavy, box-like nebulizer he called the “Bennett bird,” that helped keep his airways open. He attended military school and then Rice University with dreams of working for NASA.

When federal budget cuts dimmed the outlook for aerospace careers, Roggli pivoted to biochemistry and later to medicine. At Baylor School of Medicine, he quickly found himself drawn to pathology — the field that investigates disease by examining organs and tissues.

One of his first cases as a resident had “an incalculable and indelible effect on my medical career,” he said. The autopsy of a liver cancer patient revealed instead a rare cancer of the abdominal cavity’s lining: malignant peritoneal mesothelioma.

Under the guidance of a mentor, Roggli used a new technique to isolate asbestos fibers from lung tissue. The results and the process captured his interest. He became skilled in using the electron microscope, a tool powerful enough to make tiny asbestos particles visible.

Soon he was studying asbestos in workers’ lungs and diving into the emerging science of occupational disease.

For decades, asbestos fibers were used in building materials, insulation, automotive parts, and other products because they are heat-resistant, fireproof, and remarkably strong. The danger comes when the fibers are inhaled; and over time, they can lead to lung cancer, asbestosis, and a rare aggressive cancer known as mesothelioma.

Although asbestos use has fallen sharply, and many applications are now banned or heavily regulated, it still exists in older buildings. Demolition, renovation, and certain industrial jobs continue to pose risks.

By 1980, drawn by the potential to work with Duke pulmonary pathologist Phillip C. Pratt, MD, he had joined Duke School of Medicine and Durham VA Medical Center. He rose to full professor, instructing generations of medical students while continuing to build the research base connecting asbestos exposure to disease.

His work also led him deeper into the legal system. What began with one shipyard worker’s case in 1981 became a steady stream of requests from attorneys.

Unlike many expert witnesses, he approaches the work academically, assembling detailed reports to help courts understand how occupational exposures unfold at the cellular level.

His credibility only grew. After publishing a landmark 1986 study measuring asbestos content in diseased lung tissue, he became one of the most sought-after experts in the country. In 1987 he joined the U.S.-Canadian Mesothelioma Panel, which at the time tracked just a few dozen cases. Today, the number exceeds 3,500.

What comes next and why it involves karaoke

He is still writing and teaching. He’s currently working on an autobiography titled “So Far, So Good” and editing a new medical volume on mesothelioma.

His medical-legal funding has helped support a pulmonary pathology fellowship at Duke. His first fellow, in 1996, was Tim Oury, MD, PhD, now at University of Pittsburgh, followed by Duke Adjunct Associate Professor Thomas A. Sporn, MD, and five more fellows.

Through it all, Roggli maintained the same drive that helped him defy his childhood diagnosis.

Now in his 60s, he believes a strong diaphragm, which helps the body pull air in, has been key to his survival. He’s part of an online group for older adults with cystic fibrosis, a community that consists of many marathon runners and singers. Karaoke nights hosted at home with wife Linda are fun times, but Roggli is a contender, once winning a local karaoke contest with Aerosmith’s “Dream On.”

Today the average age of the roughly 40,000 people living with CF is 36, and the disease is no longer only treated by pediatricians. New therapies are being tested every day to extend life expectancy and quality of life for patients like Roggli.

His “Carpe diem” philosophy is simple: “To live every day to its fullest, being thankful for the day at hand, is perhaps the greatest gift that we can give ourselves.”

Jamie Botta, MBA, is assistant director of communications and marketing for the Department of Pathology.