Undeterred: Erica Taylor Embraces Being a Role Model and Changemaker in Diversity and Inclusion

Erica Taylor, MD, often thinks about what her career path might have looked like had it not been for a supportive family and a lot of mentors bolstering her confidence along the way.

It certainly wouldn’t have looked like her becoming Duke’s first Black female orthopaedic surgeon, chief of surgery at Duke Raleigh Hospital, and an influential leader within the diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) realm at Duke.

In addition to family and mentor support, Taylor also credits her success as an orthopaedic hand surgeon to pipeline programs aimed at attracting underrepresented groups to medicine. They were especially helpful as she navigated her way in a field that has been labeled “the whitest specialty,” influencing her own passion to mentor others and work to eliminate inequalities in her field and department and across Duke Health. Taylor is currently the vice chair of DEI in the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and associate chief medical officer of diversity and inclusion for the Private Diagnostic Clinic (PDC).

Taylor decided by the time she was in high school that she wanted to go into orthopaedic surgery. During her sophomore year in college, she met with a local orthopaedic surgeon, hoping to learn more about the profession. Instead of offering encouragement or helpful information, he told her she wasn’t a good fit for the profession and attempted to sway her in a different direction.

“Breaking records, being the best, being competitive, that was something I grew up expecting for myself,” said Taylor, who was raised in Reston, Virginia, by a mother who was a schoolteacher and a father, Charley Taylor, who was a National Football League Hall of Fame wide receiver and coach for the Washington football team. Her father was a pioneer himself, as one of the first Black players for Washington during an era of segregation.

“That one event in college was the first time someone had created a narrative for me or had insinuated that there was something unavailable or not attainable for me,” Taylor added. “The only characteristics he knew about me were my visible diversity.”

But Taylor wouldn’t be deterred.

“I leaned on mentors from other institutions who were Black like me to instill that confidence and encouragement that ‘Yes, you can do this,’” she said.

Among those mentors were Duke University School of Medicine’s Delbert Wigfall, MD, an advisory dean, and the late Brenda Armstrong, MD, director of admissions, whom Taylor met as a rising college senior participating in a pipeline program called the Duke Summer Biomedical Science Institute.

“As soon as I met them, I knew exactly where I needed to be for medical school,” Taylor said.

After graduating from the University of Virginia with a degree in biomedical engineering science, Taylor earned her medical degree from Duke in 2006 and completed training at the University of Virginia and the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio. She joined Duke’s faculty in 2013. She earned an MBA from Duke in 2020.

A Passion for Mentorship

Today, Taylor wants to ensure that students, trainees, and faculty have the support they need to excel. She is the faculty sponsor of a mentorship program in the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery for students from populations underrepresented in medicine. Two fourth-year medical students created the program, and Taylor said so far it has gotten a great response. After putting out a call to faculty and residents to serve as mentors, in just a few days a total of 25 had signed up.

“Twenty years ago, I don't believe I would have had 25 residents and faculty of all positions, all ages, all demographics, jump on the chance to mentor underrepresented in medicine minority students,” Taylor said. “It’s a testament to how we have distributed the accountability and have instilled passion towards equity in our faculty and in our residents. We’ve made it the rule, not the exception anymore.”

“It couldn't stop with me,” Taylor said of her motivation to be a mentor and champion for mentorship programs over the years. “I had to emulate that example of success, so that when others who looked like me faced resistance, they had someone to look up to. Even in 2022, there are still variations of the things that I experience. Sometimes it’s overt, and sometimes it’s more subtle.”

Subtle but Substantive Change

Ben Alman, MD, chair of orthopaedic surgery at Duke, said he witnessed subtle forms of resistance directed at Taylor not long after she first came to Duke. During an implicit bias training session for faculty in the department, everyone was asked to partner with someone and share their experiences with diversity, equity, and inclusion. Alman said he couldn’t help but notice that no one partnered with Taylor, who was the only Black woman in the room.

To him it was “a sign that she was being thought of or treated differently than other members of our faculty.” He added, “That had me focus even more on diversity, equity, and inclusion, and I realized that it was a persistent issue in our department.”

Alman eventually named Taylor chair of the department’s DEI committee. He said she was a great fit because of her persistence and willingness to speak up against various types of discrimination, such as microaggressions.

“She’s had one-on-one discussions with people in ways that I could never have,” Alman said, adding that Taylor’s efforts fostered progressive change in the department’s culture. “It’s been a matter of making people realize they have implicit biases, educating them, and explaining how microaggressions are not okay.”

Taylor and Alman said that such changes may seem subtle, but over time, they can have a significant impact. The changes are especially important not only to their department, but also to the orthopaedic surgery field as a whole. According to the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, in 2018, just 1.9 percent of orthopaedic surgeons were Black, 2.2 percent were Hispanic, and 0.4 percent were Native American.

Taylor and Alman are hopeful that the efforts to increase diversity will make a difference beyond their department.

“We know that having a diverse workforce increases compliance for patients,” Taylor said. “By increasing the diversity of the workforce at Duke Health, we’ve made Duke Health a place where patients can feel comfortable.”

A Servant Leader

Jacqueline Barnett, DHSc, MHS, PA-C, director of the Duke Physician Assistant (PA) Program, has worked alongside Taylor on several projects that may ultimately impact those providing care to diverse communities. Barnett and Taylor are both part of the leadership team for the Duke Advanced Practice Provider Leadership Institute (APPLI). The aim of the yearlong program, which is open to advanced practice providers including advanced practice nurses, physician assistants, and other non-physician providers, is to develop a pipeline of health equity leaders.

Barnett, who like Taylor has made history at Duke — by being the first Black PA program director — isn’t surprised that Taylor was selected to APPLI’s leadership team. Barnett said it’s a reflection of her ability to be what Barnett calls a servant leader.

“Some leadership positions are about people just doing what they can to advance themselves, where servant leaders are more concerned about the people that they serve and improving communities,” said Barnett, who is also chief for the Division of PA Studies in the Department of Family Medicine and Community Health. “Her leadership is around being that servant leader, pushing through doors to help create and improve opportunities for others and not being afraid to engage in some very difficult conversations with those who are in positions of influence.”

Creating Inclusive Administrative Leaders

Taylor’s role with the PDC aligns with the DEI work she has done in her department and other areas at Duke. Appointed in December 2020, Taylor was the first person to hold the role of chief medical officer of diversity and inclusion at the PDC. Among the innovative elements she brought to the position was requiring first-year PDC administrative fellows to complete a rotation with her. During weekly meetings, Taylor and the fellows explore ideas and work to implement programs that will improve diversity, equity, and inclusion throughout Duke Health.

Taylor believes the PDC administrative fellowship program is the one of the first to have a DEI component built into it.

Kelly Page, MHA, a second-year administrative fellow with the PDC, has worked closely with Taylor on several projects over the past two years and considers Taylor to be a mentor. Together, they worked on a portion of the Clinical Enterprise Strategic Plan dedicated to longitudinal learning experiences that advance health equity. Page works on a team that identifies and catalogs diversity, equity, and inclusion trainings and courses that currently exist at the PDC and across other Duke entities.

Page said cataloging the educational offerings aligns with many of the aims outlined in the School of Medicine and Duke Health’s Moments to Movement initiatives.

“We want to make sure that we are leveraging the incredible diversity, equity, and inclusion learning experiences that are already available here at Duke,” Page said. “There are so many resources available, and we are trying to improve awareness of what exists, improve access to the trainings, and identify gaps to inform which trainings should be developed in the future. I think it is more than just saying we value diversity, but we are showing through action that we are investing time and resources into projects like these and so many others.”

Even though Page, who holds a Master of Healthcare Administration degree from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, will work in a non-clinical field after her fellowship is complete, she said her time spent with Taylor has been invaluable and will influence her career going forward. During the fellowship, Page discovered a love for health care strategic planning, which she attributes to Taylor.

“She’s a surgeon, and I’m an administrator, but it has been inspiring to see how well she navigates being the first or sometimes being the only,” Page said. “I appreciate how, as a Black woman, as one of the leaders of this organization and a leader in her profession, she really navigates her walk with poise, grace, and excellence.”

Bernadette Gillis is a Senior News Writer/Producer for Duke University School of Medicine Office of Strategic Communications.

Video by Jim Rogalski, senior video and multimedia producer for Duke University School of Medicine Office of Strategic Communications.

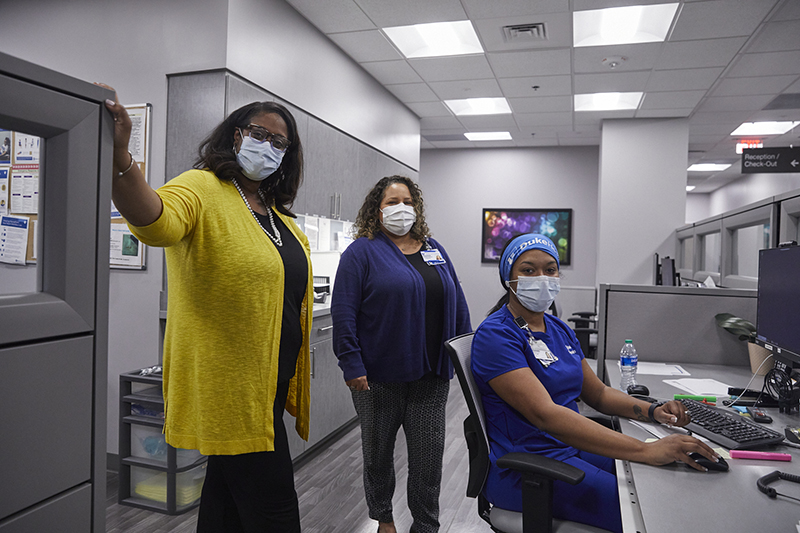

Feature photo by Jade Wilson.