The Right Environment

New faculty recruit Opeyemi Olabisi is on a mission to revolutionize the prevention and treatment of kidney disease

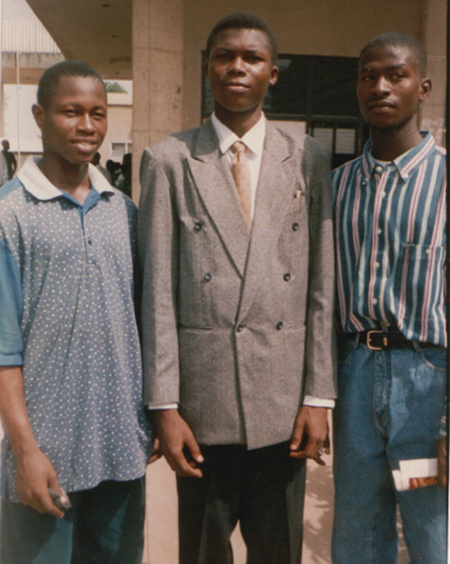

Opeyemi Olabisi, MD, PhD, learned to ride a bicycle when he was 12 years old. He was living in Nigeria in a city called Ilorin, and a friend’s older brother, Yemi, showed him how to keep the wheels moving and the bike upright. That made Yemi an indelible part of Olabisi’s life.

“Everybody remembers who taught them how to ride a bicycle,” he says.

Later, when Olabisi was going to college in New York City, he learned that Yemi had developed swelling in his legs, had gone to see a doctor, and was diagnosed with kidney disease. Yemi was soon on dialysis, and he died before he turned 30.

Both Yemi and Olabisi are from the Yoruba people of western Africa. An estimated 30 percent of Yoruba – and 12 percent of African Americans – have two variants of the APOL1 gene, which can be traced back 6,000 years to a mutation in Africa that provided some protection against sleeping sickness, but also has harmful effects on the kidneys. APOL1 is now associated with high risk for kidney diseases such as focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), hypertensive nephrosclerosis, and HIV nephropathy.

Yemi’s kind friendship and early death inspired Olabisi to dedicate his career as a physician scientist to studying APOL1 and to finding a way to treat and prevent kidney diseases.

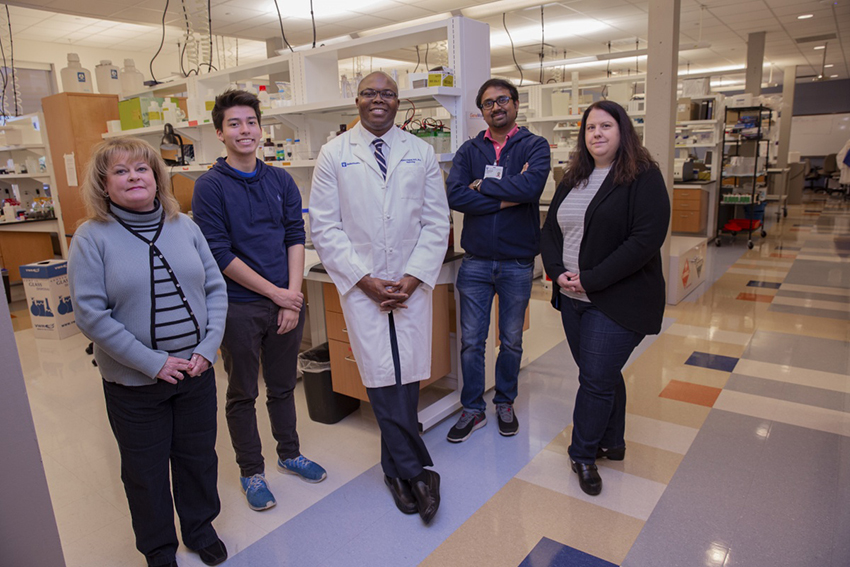

Olabisi is a rising star who was jointly recruited to Duke University in 2019 by the Department of Medicine and the Duke Molecular Physiology Institute (DMPI) – and he is in a hurry to make an impact in the lives of patients.

People with kidney disease often require regular dialysis, a mechanical intervention for removing excess fluids when failing kidneys can’t adequately do so. But fifty percent of people on dialysis don’t live more than three years. The African-American community is disproportionately affected. While 17 percent of the U.S. population suffering from kidney disease are African American, Olabisi says 30 to 40 percent of the patients on dialysis are African-American. The APOL1 gene is a major contributor to that high number.

“Patients that need therapy can't wait,” says Olabisi. “That's where my sense of urgency comes from.”

Insights from his research could pave the way for innovative prevention and treatment of APOL1-associated kidney disease.

Olabisi was recruited to Duke from Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and Harvard Medical School, where he had completed residency and fellowship and joined the faculty. Both his PhD and his MD are from Albert Einstein College of Medicine at Yeshiva University in New York. He joined Duke as assistant professor of medicine in the Division of Nephrology.

After finishing his fellowship training at MGH, Olabisi moved across the Harvard campus to do postdoctoral work in the laboratory of Martin Pollak, MD, chief of nephrology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Upon completion of his postdoctoral training, he returned to MGH to set up his own independent research laboratory. He soon began to search for the right environment to expand his research and he was attracted to Duke because of the caliber of people within the Division of Nephrology, at DMPI, and across the institution. And Durham, with its large African-American population – about 40 percent Black – is a community that can both help him advance the science and be served by the knowledge to come.

The most beautiful cell

Olabisi works with podocyte cells, which make up the outer epithelial lining of a part of the kidney called the glomerulus, the third layer through which blood is filtered.

“Think of them as the last line of barrier that prevents a kidney from losing protein into the urine,” says Olabisi. “They are probably the most beautiful cell in the body, but I'm biased.”

Podocytes don’t reproduce, and the amount you are born with is all you will ever have. And mice don’t express APOL1, so he has to study human samples, which are hard to collect. To overcome this obstacle, Olabisi uses blood samples from his human study subjects to create induced pluripotent stem cells that he can reprogram into podocyte-like cells. Using these “podocytes in a dish,” Olabisi investigates the molecular pathways of disease activated by the variant APOL1 gene, as well as the reason why some people who carry the mutation are able to avoid kidney disease. (Watch his 2019 Medicine Grand Rounds presentation.)

Samira Musah, PhD, assistant professor of engineering, is another recent joint faculty recruit to Duke (to Nephrology and the Pratt School of Engineering). She helped develop the method for creating podocyte-like cells from induced pluripotent stem (IPS) cells. (Watch her recent Medicine Grand Rounds presentation.)

Olabisi and his lab used podocyte-like IPS cells to study how the APOL1 variants cause toxicity to this precious set of cells. The research was published last month in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

A collaborative home, a community partner

Before COVID-19 temporarily shut down DMPI and Olabisi’s lab in March (along with nearly all of the rest of the research endeavors across the School of Medicine), he had just begun his outreach to the African-American community in Durham, forming an alliance with local clergy to begin recruiting individuals to the APOL1 study of kidney disease in people of African ancestry. Nadine Barrett, PhD, director of strategic partnerships at the Duke Clinical and Translational Science Institute, has been a key facilitator of this community engagement.

There's already a lot of interest in the community, said Olabisi, but also impatience.

“‘Why is it taking so long for us to be hearing this now?’ they ask me,” said Olabisi. He explains to them that the APOL1 gene was only discovered in 2010, and he’s on a mission to uncover its secrets.

Olabisi is one of a dozen physician scientists at DMPI, which fills the spacious Carmichael Building in downtown Durham. DMPI provides a collaborative home and place for researchers such as Olabisi to benefit from the proximity of other basic and translational scientists around them.

Chris Newgard, PhD, the W. David and Sarah W. Stedman Distinguished Professor of Nutrition in the School of Medicine and director of DMPI, has had a long and illustrious career in science. He says it is immensely satisfying to be able to mentor and watch the cadre of early-career faculty members currently working at DMPI.

“I see them coming down the hall with excitement, energy, and creativity, and Ope is right there in the middle of that,” says Newgard.

Olabisi says that scientists are like the cells that they culture.

“Our ability to reach our potential is influenced very heavily by our immediate environment. So in that way we are also like cells. If you put cells in a good environment, they thrive. The DMPI is a very rich environment. You know, you can’t go anywhere in that building without passing someone smart.”

Newgard notes that it is predictably difficult to move from one institution to another, requiring time to relocate equipment and samples, recruit a new laboratory team, and get oriented to Duke’s complex organization.

“It was even harder for Ope during COVID-19, but typical of him, he remained positive and bounced back fast,” says Newgard.

Duke’s swift and safety-conscious response to the pandemic in March 2020 meant Olabisi had to stop meeting with those clergy, and his lab had to shut down the still-immature stem cell lines they were developing.

Don’t stop pedaling, you could imagine Yemi telling a younger Olabisi.

So Olabisi reached out to another member of DMPI, Svati Shah, MD, professor of medicine and senior faculty at DMPI, to explore partnering with the MURDOCK Study, Duke’s landmark longitudinal translational research study working to reclassify health and disease. Shah is helping Olabisi to work through MURDOCK to recruit residents of Kannapolis, NC, to the APOL1 study, which is collecting blood samples from self-identified African Americans/Blacks either free of kidney disease or who have kidney disease diagnosed by biopsy.

“Few physician-scientists can summon such a unique blend of scientific talent, vision, personal charisma, integrity, and passion. We are thrilled Dr. Olabisi chose Duke as his academic home.” – Myles Wolf, MD, MMSc

And as the pandemic developed, Olabisi and others realized the APOL1 gene is an important factor in the disparities of people suffering most from COVID-19.

“It turns out that African-Americans who have two copies of this APOL1 mutation actually have a higher risk of COVID-induced kidney failure,” says Olabisi.

That unholy alliance between the gene mutation and deadly kidney diseases is a Pandora’s box that he very much wants to shut, he says, pointing to grand projects such as the Manhattan Project, landing on the moon, and now Operation Warp Speed to produce one or more COVID-19 vaccines. Olabisi wants the United States to set its collective mind to solving kidney disease with the same investment of will and resources.

“The amount of resources we put into studying kidney disease does not reflect that same commitment that you would expect given the number of people who die from kidney disease.”

The U.S. spends more than $40 billion annually to treat patients with end-stage kidney disease. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ranks kidney disease as the number nine cause of mortality in the U.S., where more than 50,000 people die each year from kidney disease.

“We spend more money taking care of end-stage kidney disease than we spend for the entire NIH research budget,” says Olabisi. He wants his lab to be part of a new approach, and he believes studying APOL1 can revolutionize patient care.

The National Institutes of Health sees the potential. In October 2019, Olabisi received the NIH Director’s “New Innovator” award that supports high-risk/high-reward work being done by early-stage investigators. Olabisi is using the $1.5 million to fund his work to connect with Durham community leaders, local Black churches, and the MURDOCK cohort. The more individuals he can recruit to the APOL1 Study, the more stem cells he can create and study.

Myles Wolf, MD, MMSc, professor of medicine and chief of the Division of Nephrology, recruited Olabisi, and he knew that Olabisi would flourish here.

“Few physician-scientists can summon such a unique blend of scientific talent, vision, personal charisma, integrity, and passion,” says Wolf. “And to be able to do so to study a disease that touches him so personally – Ope offers great hope for our field to improve kidney health in the future. We are thrilled he chose Duke as his academic home.”

Wolf and Kathleen Cooney, MD, chair of the Department of Medicine, nominated Olabisi for the Whitehead Scholars Award that helps attract and nurture the most promising biomedical researchers to the faculty at Duke. Olabisi received the award earlier this year.

This summer, Olabisi participated in the Department of Medicine Innovators Academy, an eight-week course created by Cooney and the Duke Innovation and Entrepreneurship Initiative for early and mid-career faculty interested in advancing new ideas, interventions, and technologies.

Olabisi is racing to help more patients live longer and better lives. He hopes his work will mean more people will have the opportunity to help a child learn to ride a bike.

Anton Zuiker is communications director for the Department of Medicine.

Photos, unless otherwise noted, by Ted Richardson.