For Paul Wischmeyer, Patient Advocacy Is Personal

In an August 2022 Twitter video, Paul Wischmeyer, MD, swivels his wife, Michelle McMoon, PA, PhD, then picks her up and spins her over his head in a cartwheel lift. They're dancing the Argentine tango in the Carolina Classic Ballroom Dancing Competition.

It's a remarkable sight, considering that just four months earlier, he had tweeted from a bed at Duke University Hospital that after three abdominal surgeries he was facing the complication he feared most.

"Thankfully, I am no longer intubated and on a breathing machine," he posted. "This will be quite a hill to climb, but I know and believe I will recover."

This procedure marked the 27th surgery of Wischmeyer's life. As a teen, he was diagnosed with ulcerative colitis and inflammatory bowel disease and had emergency surgery to remove his entire large bowel. Since then, he had an ostomy (in which the intestine is diverted through an opening in the abdomen).

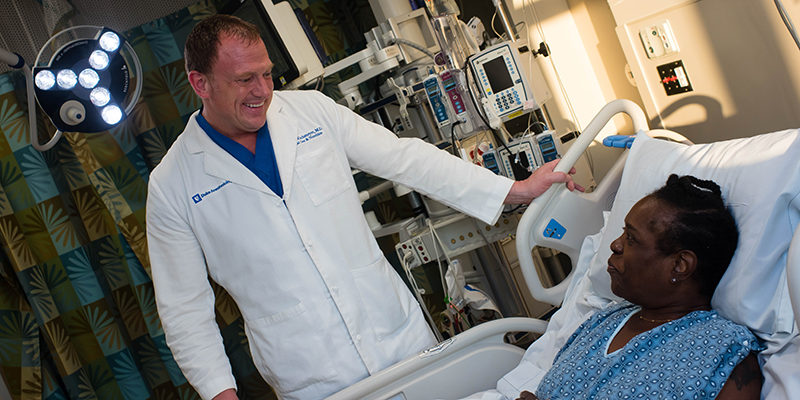

Those early medical experiences, some of which were less than ideal, inspired him to become a doctor. "I got the sense that I was thought of as more of a job to be done, or a box to be checked on a list, than as a person," he said. Wischmeyer works to change that for others and to help people with complex illnesses like his own recover better and faster.

Wischmeyer, professor of anesthesiology and surgery, is a critical care physician and the physician director of total parenteral nutrition (feeding by bypassing the digestive system, such as via IV) and the nutrition support service at Duke University Hospital. He rounds in the intensive care unit (ICU) to see patients with specialized nutrition needs, and he is there for some of the most vulnerable times in his patients' lives. He works hard to make these moments less scary, because he has been there so many times himself.

For instance, body language matters. "Sit down at eye level with the patient, or stand there like you want to be there, not with one foot out the door," he said. "Never cross your arms in front of a patient. It looks like you either don't want to talk to them, or there's something you're not telling them. Families and patients are anxious enough."

Wischmeyer also reminds physicians that procedures that they see as routine can be scary and painful for patients. "Small amounts of sedatives and anxiolytics and better use of pain meds can change that dramatically," he said. When he was a child, doctors routinely performed colonoscopies, upper GI endoscopy, central IV lines, and large radiology drain placements on him without any sedation, he said. "One of the reasons I pursued anesthesia training was that it gave me the ideal skillset to sedate people for things that no one else sedates for safely."

Despite the complications with his recent surgery, Wischmeyer gained his strength back faster than when he had a similar procedure 14 years ago when he was younger and not as sick, he said. He attributes that to applying precision nutrition and prescribed exercise to aid in his recovery, something that is the topic of his own research funded by the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Defense.

Exercise as Medicine

Wischmeyer's belief in the ability of exercise to heal was cemented just before medical school. He had always played basketball and soccer, but in college he took up running thanks to a surgeon who at a follow-up visit told him he was looking a little out of shape. "I thought, 'No one has ever told me that. I'll show him,'" Wischmeyer said. "I started running my senior year of college and ran every day for the next year."

At the end of that year, he needed surgery to remove a nonfunctional, internal “ileal-J” pouch that kept getting infected. It was risky because of heavy scarring in Wischmeyer's abdomen his surgeon had seen during another procedure a year earlier. The surgery was predicted to take eight hours, but it took only four, and his surgeon told him much of the previous scarring had healed. "He said to me, 'I don’t know what exercise you have been doing for the last year, but don’t ever stop. It probably saved your life,'" Wischmeyer said.

In medical school he started lifting weights with professional bodybuilders. “I learned more about metabolism and nutrition and fitness from a year and a half in that gym than I would learn in my whole career," Wischmeyer said. "I gained 60 pounds in a year learning how to lift correctly and how to eat and use legal nutrition supplements correctly."

Leading up to his most recent surgery, Wischmeyer had a serious and scary bowel obstruction episode in January 2022, while he and McMoon were on vacation in Hawaii. He had to be admitted to an unfamiliar hospital that had never seen a complex case like his and have a tube inserted to remove fluids from his stomach.

Once home, he scheduled a procedure at Duke, where he knew he would be in great hands. The expertise of abdominal surgeon Debra Sudan, MD, professor of surgery, was one reason why Wischmeyer decided to come to work at Duke in 2016. "There were a lot of good reasons to come to Duke as a researcher and a faculty member, but from a patient's point of view, Deb Sudan is one of the best in the world at operating on people like me," he said.

Sudan and a team of radiologists who reviewed his CT scans agreed that Wischmeyer needed his gall bladder removed. In addition, his small bowel was trapped in bands of scar tissue called adhesions, McMoon explained. "The adhesion is kind of like a rubber band around a very soft, squishy water balloon, the bowel being the water balloon," said McMoon, director of education and professional development at WakeMed Health. "If you cut the band off, then you theoretically think the bowel might open back up again and you won't have to cut out a section of it."

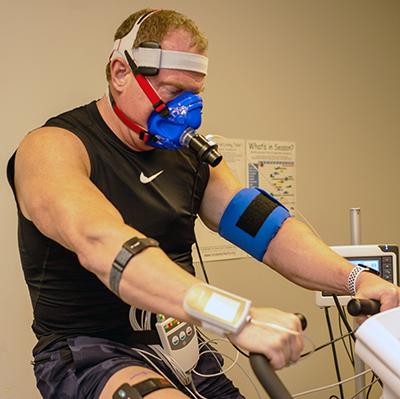

With two months to prepare, Wischmeyer underwent "optimization studies" to determine ideal preparation and recovery regimens. He had a cardiopulmonary exercise test to determine optimal heart rate for exercise, an ultrasound to measure muscle mass, and an indirect calorimetry test to measure his personal calorie requirements.

He uses many of these techniques in his clinical research. For instance, in a study of COVID-19 patients in the ICU published in September 2020, indirect calorimetry showed that these patients needed more and more calories as their hospitalization went on, said Laura Van Althuis, RDN, a clinical dietician and research coordinator who works with Wischmeyer on such studies. "The study confirmed there was really no predictive energy equation that would have hit the nail on the head for these patients," she said.

Most hospitals estimate nutrition needs using equations. But indirect calorimetry is "the gold standard for the measurement of energy," Van Althuis said. It gauges metabolism by measuring the oxygen breathed in and the carbon dioxide breathed out. "All of our patients are unique," she said. "A weight-based equation that works for a 30-year-old might not apply to the lower metabolic rate of an 80-year-old."

Indirect calorimetry was especially helpful for Wischmeyer because he has a good deal of muscle mass. "We figured out that after I had surgery, I needed about 3,000 calories a day just at rest to maintain my body mass, which I would've never guessed," he said. Duke Health has approved launching an indirect calorimetry team for routine clinical care, led by registered dietitians — one of the first of its kind, Wischmeyer said. He and Van Althuis will oversee it.

Dreaded Complications

Sudan performed Wischmeyer's surgery in late April 2022. She removed the gall bladder and scar tissue but also had to remove some more of his bowel. The procedure took 14 hours. Family members feel isolated in the waiting room during such a long surgery, McMoon said. But a nurse anesthetist provided McMoon updates by cell phone throughout the procedure, even after she had finished her shift.

Wischmeyer was walking within 12 hours of surgery and soon started receiving nutrients via IV. But a few days later he woke with a fever and found his gown soaked from an intestinal leak through his incision. “It's a very bad complication," McMoon said. "Dr. Sudan found the leak right away and stitched it up."

After the second surgery, Wischmeyer was working out with exercise bands and walking the halls of the ICU. But the leak began again, requiring another emergency surgery. This was the complication he feared most: a persistent intestinal fistula, or an ongoing leak that can take months to heal. “I was devastated," he said. "But I knew I couldn’t give up and I had to keep fighting even harder now to recover.”

Wischmeyer stayed in the hospital for 12 days after the third surgery. He and McMoon praise his entire Duke Health care team, especially the ICU nurses. “It took courage for the nurses, who all knew Paul, to provide such incredible care to him knowing that a week prior he was standing there leading rounds while they presented cases to him,” McMoon said. Wischmeyer said, "We felt so safe and cared for." In addition, Krista Haines, D.O., assistant professor of surgery, navigated the fine line of caring for Wischmeyer as an attending physician and visiting regularly as a friend, McMoon said. “She was the most supportive friend and colleague we’ve ever known.”

When Wischmeyer went home in May, he was still receiving 100% of his calories by IV or parenteral nutrition feeding. It stayed that way until the end of July. Despite that, he lost only 10 pounds during the whole ordeal. He gained it back in just two weeks.

A few days after he was discharged, Wischmeyer was lifting weights and riding a bike in his home gym, despite having an open incision with a drain. “He would lie on a bench with his abdomen down so he wouldn’t flex his abdominal muscles,” McMoon said. Meanwhile, she kept his feedings on schedule and rotated three different antibiotics. "Even with my training, it was hard," she said.

Thankfully, the fistula healed in August, Wischmeyer said. Just eight weeks after his last surgery, as soon as Sudan gave him the okay to lift more than 10 pounds, he and McMoon started rehearsing so they could perform in their August dance competition. To their surprise, he was immediately able to still lift McMoon over his head. Just a few weeks later, they competed with multiple dance routines. In September 2022, he returned to on-site work in the Duke University Hospital surgical ICU.

It's hard to imagine where Wischmeyer gets his motivation, which still amazes McMoon after seven years of marriage.

"People who haven't been sick their whole life don't know what it is actually like to fight for your life. Being told you might die when you're 15 years old is something you never forget," she said. "He always says to me, 'I'm not going to let this disease dictate my life. I'm going to dictate my life.'"

Angela Spivey is a senior science writer and managing editor for the School of Medicine’s Office of Strategic Communications.

Photos by Jack Newman and Jim Rogalski.

Main image: Paul Wischmeyer’s experiences as a patient inform his work as a researcher and professor of anesthesiology at Duke University School of Medicine.

Magnify is Duke University School of Medicine's online magazine, publishing two stories a month focused on the people who make up the School of Medicine community.