Jumping in Feet First

Duke University School of Medicine is launching a new “patient first” curriculum that puts students in the clinic earlier and trains them in social determinants of health, data science, and leadership

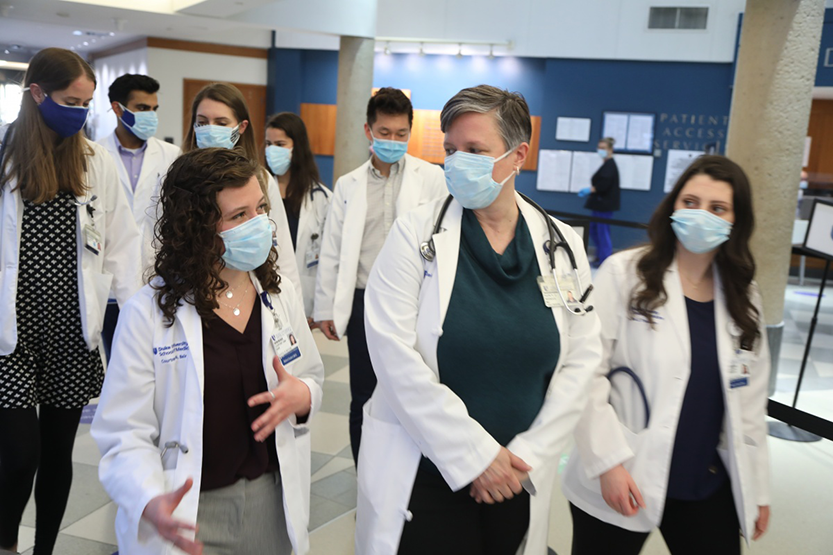

Meghan Sullivan and Ivana Premasinghe still can’t believe they got to spend their very first week of medical school in the clinic, conducting patient interviews and learning basic exam skills like blood pressure reading and heart rate monitoring.

The first-year Duke University medical students are part of a pilot class for Duke University’s new “Patient First” medical school curriculum. Implementation of the new curriculum has already begun and will continue to roll out over the next four years. The revised first year experience, launched in August 2020, includes a new Clinical Immersion course, which allows students to spend time with patients almost immediately.

“It was a great way to begin medical school before starting our more science-focused classes,” said Premasinghe. “It was nice to be reminded of what we'll get to do during our second year in medical school and what we'll get to do in the future as doctors.”

“It really gets you on the ground running. You feel like you're immersed in medicine right away,” said Sullivan.

This sense of immediate immersion in the clinical environment is exactly what School of Medicine faculty and administrators sought out to create when they began planning the new curriculum in 2017. Over the last four years, more than 70 faculty, staff, and students have served on the curriculum development committee which has led development of the new curriculum.

The first question the group asked was: What is the skill set that a physician will need in 2030?

The Physician of 2030 is Patient-First

“We began looking at our current curriculum and trying to see how well it fit with what we expect the physician to know in 2030,” said Ed Buckley, MD, vice dean of education who along with other Medical Education leaders, spearheaded this initiative.

For years, Duke has offered a unique curriculum and set the standard nationally by allowing students to care for patients during their second year, a full year earlier than their peers, and spend one full year to focus on research or other projects of their choice. Faculty leaders intend to keep these key elements of Duke’s current curriculum while developing and incorporating new and important facets.

“We decided that we were missing some good things that we needed to include and some of the things that we were doing just weren't as applicable anymore going forward,” said Buckley. “So we brought a group of educators, clinicians, basic scientists, and students together, and said, ‘Okay, what is the skill set that physicians will need in ten years?’”

Rather than only teaching facts that can change with each new technological advance or discovery, medical education leaders decided to focus on teaching strategies and concepts that would help future physicians easily adapt in the midst of change to offer the best patient care.

Watch video about new MD curriculum

Through many thoughtful discussions over several years a clear picture emerged: a physician must be well versed in medical vocabulary. They must be a self-learner, a critical thinker, a problem solver, and skilled in data interpretation and communication. A physician must be able to care for the ‘whole patient’ in their context as a human being with a family, living in a community, and impacted by their society. This includes recognition of the social drivers of health, including racism, access to care, and trauma. That’s how the idea of a “Patient First” curriculum was born.

“The Patient First Curriculum is designed so that physicians of the future can better address the needs of patients and communities. It is focused on teaching our medical students important knowledge like how community health impacts individual health and essential skills like how to have effective conversations with patients from diverse backgrounds,” said Aditee Narayan, MD, MPH, associate dean of curricular affairs.

The “patient first” phrase refers to the chronology of medical school (students see patients first before beginning any other coursework) but also to the mindset that faculty educators hope to foster in students.

So often, medical students get through their first year without really understanding the ‘why’ behind what they’re learning, said John Roberts, MD, assistant professor of medicine and a member of the curriculum development committee. Instead, they’re focused on memorizing very technical information, something he calls the “Knowledge Olympics.”

“Sometimes, one of the things we forget to talk about during the first year is the ‘why,’ said Roberts. “Why are we teaching this? How is this knowledge going to translate into a behavior, a skill or an attitude that is actually going to impact a patient in a positive way? Medical school is very demanding. We ask students to go through examinations and personal sacrifice. I want that to be worth it. In other words, I want them to clearly see a connection between what they're learning and their future self and their future self’s ability to take care of a human.”

This patient-first mentality is being developed through new courses, but also by incorporating ‘knowledge threads’ into existing courses. These threads teach students over the course of the entire four years about the social determinants of health, how to leverage data science to best care for a patient, and how to be an advocate for patient health through innovation and leadership.

A big part of designing the new curriculum is figuring out how to weave these threads together seamlessly through the coursework so that they’re always in the back of the student’s mind, said David Gordon, MD, associate professor of surgery and medical undergraduate education director in the School of Medicine.

“Through this new curriculum, we are re-framing how the students think about what they’re learning,” said Gordon. “Traditionally, the first year of medical school has been organized around body systems. But really what we need is to be organized around patient scenarios and patient presentations.”

“Whether students choose to become a physician-scientist, a public health advocate or a clinician in clinics and hospitals, they should think about patients first,” said Narayan. “The ideal physician integrates all aspects of care at the bedside – they must consider the underlying biomedical principles, communicate compassionately, consider social context and drivers, balance ethics, consider health care costs, and appreciate the role of new technology. Teaching our students to do this from day one allows them four years of practice before they graduate, setting them up to be role models and change agents.”

Medical education leaders are quick to point out that the program will still have a strong emphasis in basic science and clinical research.

“We still have as a cornerstone of our curriculum a research heavy third year where the students can go and do a project over a longer period of time and do a deep dive into a particular subject,” said Buckley. “That subject could be in the basic science laboratories, or it can be in a clinical realm, or it could be a second degree, but it just adds to the clinical experience and the educational experience they get, so that we hopefully graduate individuals who are going to be very innovative and creative and will approach problems with a different view than someone who hasn't had that background.”

Built for Students by Students

School of Medicine leaders were very intentional in inviting students to be part of the committee designing the new curriculum, and they have played an important role in providing new ideas and feedback.

Chris Lea, a second-year medical student, serves on a subcommittee devoted to making recommendations on how Duke can become a more diverse and just institution. The subcommittee is charged with making recommendations to the Dean about ways to incorporate anti-racism initiatives, and efforts to promote diversity, equity and inclusion.

Often, he said, this involves training students to consider how social determinants of health will impact patient diagnosis and treatment.

“Essential to our new curriculum is the principle of inclusion – promoting meaningful connections through addressing racism and health care disparities,” said Narayan.

Sonali Biswas, a third year medical student, serves on the Student Advisory Committee and is also involved with incorporating the current Leadership Education and Development (LEAD) curriculum into the Patient First Curriculum.

“We are working to incorporate training for essential leadership and communications skills into the curriculum,” said Biswas. "Learning to apply the core principles of Duke's leadership model--emotional intelligence, integrity, teamwork--is essential to effective patient advocacy."

First year students Sullivan and Premasinghe also serve on the Curriculum Committee, where they provide live feedback on the first year as they’re experiencing it.

“It's a wonderful opportunity for students to have their voice heard,” said Sullivan. “This is something I really wanted to do and was excited about because I’m interested in working in medical education in the future.”

“Duke is working hard to make more well-rounded physicians and create this environment where faculty and students are constantly thinking about their role in the community and how they can have an impact on healthcare for the wider population,” said Premasinghe.

In August 2021, the new and approved first year will launch. The curriculum leaders are in the process of developing pilots for a new second year.

“Curriculums are living organisms, if you will,” said Buckley. “They're really never static. Even though we're talking about doing a, ‘major revision,’ which we are, we've been changing our curriculum every year in subtle ways as we encounter new ideas, new ways of approaching problems, new ways of teaching. The technology has changed tremendously over the years and our understanding of how adults learn has as well. When I went to medical school, we sat in a classroom, we took notes. There was a sage on the stage who pontificated eloquently about a particular topic and we sort of absorbed it. That's not a good way for adults to learn. Adults learn better if they understand why they need to learn the particular information and if they can use that information relatively quickly. So we have developed a curriculum which tries to keep those principles in mind.”

Photos and video by Jim Rogalski, director of video productions and senior public relations specialist in Duke Health Development and Alumni Affairs. Story by Lindsay Key, senior science writer in the School of Medicine and editor of Magnify.