Joining Forces to Fight Childhood Obesity

As a pediatrician, Sarah Armstrong, MD, has devoted her career to improving children’s health and well-being.

“My training allowed me to deal with most of the pediatric conditions that came into my office,” Armstrong said, “but by the late 1990s – early 2000s, something different was emerging. More kids were coming in with obesity and exhibiting adult-type problems.”

Today, nearly one in three kids is overweight or has obesity. Obesity is defined as having a body mass index (BMI) at or above the 95th percentile, and overweight is defined as a BMI at or about the 85th percentile. BMI is calculated using weight and height.

“Pediatric obesity is a precursor to many chronic health diseases in adults,” Armstrong said. “It is associated with adult obesity, asthma, heart disease, diabetes, some cancers, especially colon, breast and prostate cancers, and may also affect children’s emotional health.” Children with obesity have an 80% chance of staying overweight for their entire lives.

These statistics troubled Armstrong, so when she joined Duke in 2006, she immediately set forth to create the Healthy Lifestyles Program, now one of the largest outpatient pediatric obesity clinics in the country. It has provided treatment to over 15,000 children aged 2 – 18 using a multidisciplinary approach to care. Children with obesity are treated by a team of medical providers, dieticians, physical therapists and behavioral counselors.

The program helps children and their families gain nutritional knowledge and build self-esteem. Armstrong encourages her patients to focus on the things they can control like eating healthy foods and staying active. “We meet each child and their family where they are in their own health journey and encourage their good behaviors,” she said. “Those who complete one year of treatment show a significant drop in BMI body fat percent, blood pressure and cholesterol.”

Laying the Foundation

In 2015, Armstrong connected with Duke colleagues Svati Shah, MD, cardiologist and professor of medicine, Asheley Skinner, PhD, professor of population health sciences, and Jennifer Li, MD, pediatric cardiologist and professor of pediatrics. The four quickly found a common theme in their work. “It started as a simple conversation between friends and colleagues,” Shah said. Shortly after, an idea emerged: the four scientists could use the Healthy Lifestyles Program as a bedrock to further investigate pediatric obesity.

From there, two intertwined interdisciplinary research studies that span basic science to clinical research formed. The Hearts and Parks program, led by Armstrong, Shah, Li, and Skinner, is funded by the American Heart Association. It aims to address knowledge gaps in effective treatment of pediatric and adolescent obesity by comparing treatment options and researching the biology of obesity in children and adolescents. The program is looking at unique differences in the gut microbe and related metabolites and proteins among children who are overweight compared to those in a healthy weight range.

The second study – Pediatric Obesity Microbiome and Metabolism (POMMS) – is led by John Rawls, PhD, professor of molecular genetics and microbiology at Duke, and Patrick Seed, MD, PhD, associate chief research officer for basic science at Northwestern University. Funded by an NIH R24 grant, the program aims to better understand how gut microbes influence metabolism in adolescents with obesity before and after weight loss intervention.

These two projects involve 13 collaborators from across Duke campus who are taking a clinical and multi-omics approach to learn more about pediatric obesity, assess the effectiveness of a clinic-community collaboration to treat it, and better understand how the microbiome and metabolome contribute to intervention success.

Nearly 300 children aged 10-18 in Armstrong’s Healthy Lifestyles Program enrolled in the POMMS project. Of those, 71 participants made up the healthy weight control, while 223 participants had BMIs at or higher than the 95th percentile for their age. The Hearts and Parks program recruited 327 participants from the Healthy Lifestyles Program aged 5-18 with BMIs at or above the 95th percentile.

Shaping Healthy Minds and Bodies

As a cardiologist, Shah understands the importance of attacking obesity at a young age. She treats adult patients who already have heart disease but also tries to help prevent patients from developing it.

“Cardiovascular disease begins in youth with obesity as a significant risk factor,” Shah said. “We are now seeing traditionally adult-onset diseases like diabetes and hypertension in children and adolescents with obesity.”

Children and adolescents with high BMI levels have fewer and less severe comorbid conditions than adults, and their disease risk may be reversible by implementing healthy lifestyle changes and lowering those levels.

Typically, pediatricians check the BMI levels of children during regular well-child care visits. For children with high BMIs, they discuss incorporating changes in eating habits and physical activity. In the Hearts and Parks program, researchers compared that standard treatment plan to a treatment plan that includes clinical and community-based program interventions.

Enrollees in the program were randomly split into the two groups for six months.

The children in the intervention group received a health coach, guidance from health experts, and memberships to Bull City Fit, a community-based wellness program in Durham that includes exercise and games plus cooking classes to teach participants how to prepare healthy meals. The program is open to children and their family members.

Each child enrolled in Hearts and Parks also received a Garmin fitness tracker to help them keep track of their steps and sleep. For those attending classes at Bull City Fit, their trackers also gathered information about their activity level and number of steps per day. All enrollees received comprehensive health evaluations at the time of enrollment and at the six month mark.

After six months, the standard care group joined the intervention group for six additional months. “It was important to us to ensure that each child in the study had the opportunity to attend Bull City Fit and experience all of the benefits of the intervention program,” Armstrong said.

Results from Hearts and Parks are pending analysis, but the team is hopeful that the results will show that children in the intervention group were able to improve their overall health, lower their BMI levels and create lasting changes for themselves and their families.

Getting to the Basics – Sciences, that is

While Armstrong is focused on the clinical and Shah on the translational aspects of childhood obesity, Rawls, a basic scientist at Duke, is focused on the gut microbiome, how it changes during and after weight-loss intervention, and how it might contribute to intervention outcome.

The gut microbiome is made up of trillions of microbes that live inside the digestive tract and help break down the food we eat. “Emerging evidence suggests the gut microbiome and its metabolic products can be key mediators in obesity and metabolic disease, but there’s still a lot we don’t know.” Rawls said. “Most previous studies of the microbiome’s contributions to obesity have focused on adult stages. In contrast, we understand relatively little about if and how the gut microbiome contributes to obesity development in earlier stages of life.”

First, explained Rawls, the gut microbiome been shown to help support digestion, healthy weight, and immune, bone and brain health. Secondly, alterations in gut microbiome composition and activity have been associated with chronic illnesses in adults like obesity, insulin resistance, high cholesterol, diabetes and more. Our ongoing studies allow us to look earlier at the earlier stages of life where obesity often begins, said Rawls.

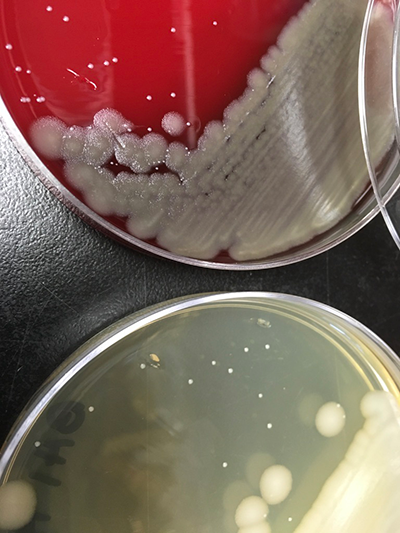

Both the POMMS and Hearts and Parks studies involved collecting blood and stool samples from the enrollees multiple times throughout their trials. By sequencing the DNA present in the stool samples, researchers can figure out what bacteria are present in that particular host’s microbiome. The POMMS team published early initial findings from the study using data from 27 enrollees with pediatric obesity and 27 enrollees in the control group. These initial findings revealed significant differences in microbiome membership between the children with obesity and those in the healthy weight cohort.

To test if these differences are causes or consequences of obesity, Rawls and senior research assistant Jessica McCann, PhD, are transplanting the microbial communities found in the enrollees’ samples into germ-free mice. Over the course of two weeks after microbiome transplantation, the mice are weighed and samples of stool, plasma, and different tissues are taken to permit microbiome and metabolomic profiling, which can help determine the association between the candidate molecular pathways in key tissues. The researchers are currently analyzing these results.

The fecal and blood samples from the POMMS and Hearts and Parks program also provided information on how branched chain amino acids (BCAAs) and other microbiota-related pathways are associated with pediatric obesity and how they change over time once interventions like exercise and nutrition changes have been implemented.

BCAAs are a group of three amino acids – leucine, isoleucine and valine – that aren’t produced by the body. Instead, they come from foods like chicken, beef, nuts, whole wheat and soy and gut microbes. BCAAs provide many physiological and metabolic benefits – they are important nutrient signals and metabolic regulators, and they can increase insulin secretion, regulate body fat metabolism and glucose, promote milk production, aid in immune health, and alter gut microbial diversity and functions.

Moderation in BCAA levels is key, according to McCann. “BCAAs are typically elevated in the bloodstream of adults with obesity,” she said. New research shows that BCAAs play an important role in the pathogenesis of metabolic disorders like obesity and diabetes as well as other chronic disorders like cancer and heart disease.

Learning the role of gut microbes, BCAAs and molecular pathways in pediatric obesity could lead to a new type of personalized medicine approach to treat it. Shah and Christopher Newgard, PhD, director of the Duke Molecular Physiology Institute, have been studying the role of BCAA in obesity and heart disease for over a decade. In her lab, Shah works on this translational aspect, studying metabolites and proteins to understand the biology of obesity beyond BCAA, and to identify potential microbiome, protein and metabolomic signatures biomarkers that may serve as prognostic or predictive factors in disease remission or targets for future therapeutics.

The Finishing Touches

“The neatest thing for me about this constellation of projects is that it has a single disease focus – pediatric obesity,” said Armstrong, ”We are all exploring causes and consequences of the disease from one end of the translational spectrum to the other in a way I haven’t seen before.”

Currently, the team is analyzing all of the data they have collected through Hearts and Parks and the POMMS programs. “We are very excited about the discoveries emerging from our collaborative team and look forward to seeing how others at Duke and elsewhere can mine the data we’ve generated from different angles,” Rawls said. Several articles have already been published in scientific journals.

Aside from publications, another important component to this work is the creation of a publicly available biorepository of patient samples and data. The biorepository can be used as a resource for researchers around the world to help generate additional data, test hypotheses and expand the overall research around pediatric and adolescent obesity.

“Our hope,” Rawls said, “is that investigators at Duke and beyond will make use of the resources we’ve generated to ask new questions about pediatric obesity.”

This is just the tip of the iceberg. Although current funding for these projects ends later this year, this is not the end of their collaboration. Rawls and Armstrong are currently investigating new avenues for grant funding.

“I see decades of work happening with this team,” Shah said.

Alissa Kocer is the communications strategist for the Precision Genomics Collaboratory.