For James Carter, Sr. Serving the Underserved Was a Calling

James Carter, Sr.’s love for reading, science and medicine blossomed when he was a young boy in Maysville, North Carolina, as he pored over the scientific magazines his mother regularly brought him from the doctor’s home where she was a housekeeper. Sharing these magazines with her son was just one of the ways Irene Carter reinforced the importance of education to her four children, and this simple act undoubtedly helped lay a foundation for his successful career as a physician.

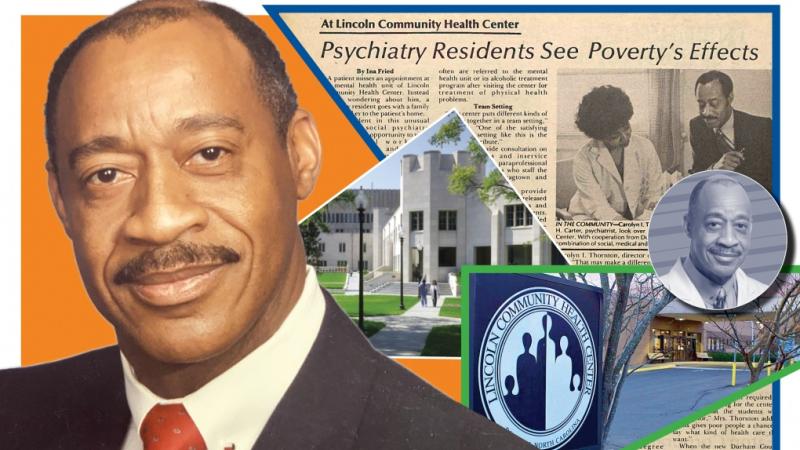

Decades later, in 1983, Carter became the first Black full professor of psychiatry in the Duke University Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, but his achievements and legacy stretch far beyond the Duke campus and health system.

After graduating with honors from North Carolina College (now North Carolina Central University), Carter entered the U.S. Army in 1958 as a second lieutenant. He spent four years as a bacteriologist at Landstuhl Army Medical Center in Germany, where he was eventually promoted to the head of his department.

Carter continued to serve his country with distinction for many years as a member of the U.S. Army Reserves, achieving the rank of Colonel, but in 1962, he headed down a new path of service: medical school at Howard University.

Helping People Live Their Best Lives

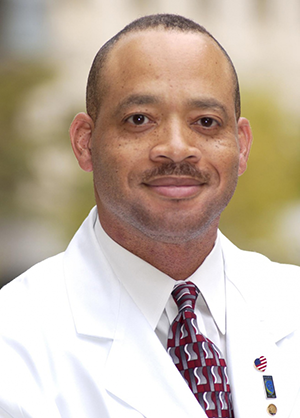

“My father was a ‘people person.’ He always wanted to go into medicine,” his son, James “Jay” Carter, Jr., MHS, PA-C, an assistant professor in the Department of Neurosurgery at Duke, remembers. “And I think he really wanted to understand how the mind works. I think that’s what led him to specialize in psychiatry.”

Tedra Anderson-Brown, MD, a mentee and later a close friend of Carter, agrees that his love of people played a role in his career choice. She also suggests his passion for psychiatry derived from his understanding that the human experience is different for everyone and his fundamental belief that everyone, including people who have a mental illness, deserve to live full and rich lives.

“I think it also came out of his faith,” Anderson-Brown adds. “He was truly a servant leader.” A devout Christian throughout his life, Carter earned a master’s in divinity from Shaw University and sometimes prayed with patients at their request.

While at Duke, Carter took on myriad roles, including educator, researcher and clinician at the Duke University Medical Center, supervisor and mentor to psychiatry residents and fellows, staff psychiatrist at Lincoln Community Health Center in Durham, and senior psychiatrist at Central Prison in Raleigh, to name just a few.

A Voice for the Underserved

Carter, who passed away in 2007, was known as a physician who connected deeply with his patients and tirelessly advocated for them. He was particularly passionate about working with those in underserved populations: people of color, individuals with severe mental illness, people who didn’t have the means to access high-quality psychiatric care and individuals involved in the justice system.

“He touched so many lives,” says his wife, Elsie Carter. She recalls one letter she received from a patient after her husband passed away, who wrote, “He gave me hope when I was hopeless, and he gave me my life back when my soul was weary and wavering. I’ve never seen anyone as attentive to me as he was when I was talking to him.”

Carter believed his patients deserved the very best care and treatment he could offer, and this dedication manifested even in how he presented himself. Elsie notes that he always dressed sharply, wearing a suit and tie under his white coat every day out of respect for his patients and to set an example for up-and-coming doctors.

And the care and compassion he demonstrated toward his patients sometimes extended beyond the traditional provider-patient dynamic. “He had a few patients he’d bend the rules for,” says Ojinga Harrison, MD, an alumnus of the Duke medicine-psychiatry residency program who later became a close colleague of Carter.

Throughout his career, Carter received many awards and accolades, including the American Psychiatric Association’s 2003 Solomon Carter Fuller Award, named after the first Black psychiatrist in the U.S.; the Order of the Long Leaf Pine Award, North Carolina’s highest honor for people who have made significant contributions to the state and their communities; and several high military honors. “But you wouldn’t know about any of his accolades just by talking with him,” says his former Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences colleague Dan Blazer, MD, “He was very humble.”

His son Jay adds that, of any of his career achievements, his father was probably most proud of helping so many patients, being a voice for underserved and underprivileged people, and mentoring young Black psychiatrists.

A Mentor and Role Model

During his tenure, says Marvin Swartz, MD, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and a former colleague of Carter’s, he was one of the only Black supervisors in the department, and many Black trainees sought him out as a mentor.

One of those trainees was Anderson-Brown, a Duke psychiatry resident in the early 1990s. While she was in medical school at Duke, after deciding to pursue psychiatry, she was encouraged by then-associate dean Brenda Armstrong, MD, to connect with Carter. “He took me under his wing,” she says. “It was so incredibly valuable to me, just having him to help me navigate being a resident while not having a lot of people who were like me in the program.”

Carter helped Anderson-Brown work through specific experiences, like patients not wanting to be treated by a Black doctor, as well as sharing plenty of broader career and life advice. “He pushed me to be a better person and psychiatrist, and he always told me, ‘These challenges shape you, but they don’t define you, and they don’t change your mission.’ I think that was just the best piece of advice.”

He also instilled in her the importance of work-life balance and self-care. When he wasn’t working, Carter enjoyed spending time with his children and grandchildren, reading, riding and tending to his beloved horse, and cultivating his fruit and vegetable garden with Elsie. He encouraged Anderson-Brown, who had a young daughter at the time, to prioritize family and faith and discover a passion to nurture—and he modeled this mindset in his own approach to life.

Anderson-Brown, now the Behavioral Health Medical Director at Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina, says Carter took mentoring very personally and seriously and urged her to do the same for the next generation of psychiatrists and others in the community. She has taken this charge to heart, engaging in a broad range of outreach activities in local communities of color.

A Far-Reaching Legacy

Carter, a member of the former Social and Community Psychiatry division, played a critical role in building behavioral and mental health services in several local centers and institutions, including Lincoln Community Health Center in Durham, the Alcohol Treatment Center in Raleigh, the Johnston County Mental Health Center and the Department of Corrections. Lincoln Community Health Center has remained a popular clinical training site for Duke Psychiatry trainees interested in community psychiatry.

“His brain was always going,” says Anderson-Brown. “If something’s not there, you have to build it. You have to make it happen. He just had that kind of mentality.”

As Carter’s career began winding down at Duke in the early 2000s, Elsie, who has a background in hospital administration, proposed an ambitious new project: establishing a private mental health clinic. Together, with Elsie at the administrative helm, they founded the Carter Clinic in Raleigh, North Carolina.

A few years later, when Carter became too ill with cancer to oversee the clinic, he sold it to Harrison, who had been one of the clinic’s psychiatrists. Still the owner and CEO today, Harrison has expanded the practice to ten locations across North Carolina and plans to continue growing the clinic’s footprint.

The Carter Clinic provides a full scope of psychiatric services for children, adolescents and adults. Honoring Carter’s dedication to teaching, the clinic also serves as a training site for students in physician assistant, nurse practitioner, social work and medical assistant programs. Harrison has also initiated a research component with a project focused on integrated care.

A few features that set the Carter Clinic apart, Harrison notes, include the option of Bible-based counseling, their ability to provide suboxone treatment, their peer support services, their residential treatment program for adolescent boys and—perhaps most importantly—their high standard of care.

“Dr. Carter was a consummate research psychiatrist with a real standard of excellence, and he challenged me to maintain that standard at the Carter Clinic,” says Harrison. “That continues to be a goal for us to try to achieve.”

Honoring Carter’s Contributions

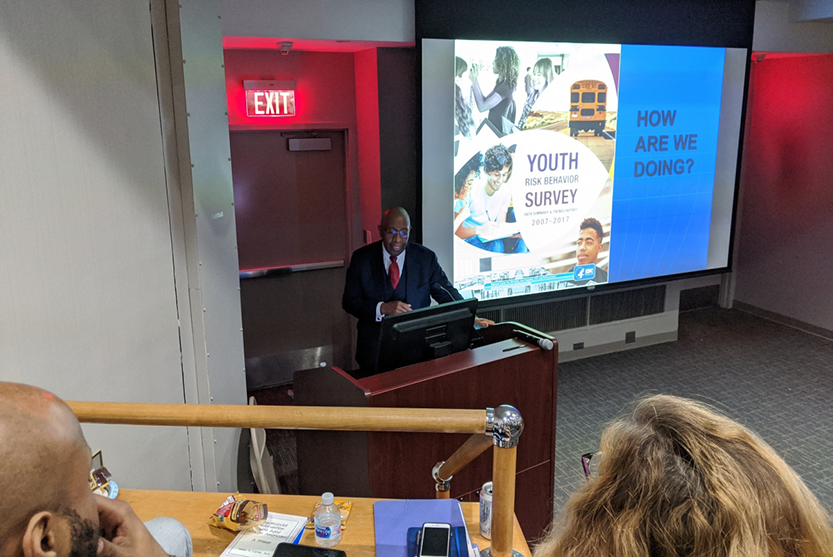

With funding from an American Psychiatric Association Minority Fellowship, Anderson-Brown established a lecture series in 1995 to honor Carter and bring African American providers and leaders in the field to Duke to speak about topics such as addictions and health disparities.

“Establishing the lecture series was a way to acknowledge how much Dr. Carter mattered to Duke and to the Duke experience,” recalls Anderson-Brown. “He really believed in what he did, and he would just bring everyone together and into his vision and thought process. He was a bridge builder.”

After Carter’s death in 2007, the lecture series became the James H. Carter, Sr. Memorial Lecture, hosted by the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. This annual lecture continues to highlight work in community psychiatry, particularly among underrepresented minorities.

In honor of Carter’s commitment to community service, Harrison and the Carter Clinic have also established the James H. Carter, Sr. Community Service Award to recognize one or more Duke psychiatry trainees each year for outstanding commitment and service in community health. The Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences collaborates with Carter’s family and Harrison to select the recipient(s). The 2021 awardees are Hira Silat, MBBS, a fourth-year psychiatry resident, and Colin Smith, MD, a fifth-year medicine-psychiatry resident.

Remembering Carter

Carter passed away from cancer on March 8, 2007.

“He was an exceptional person. His family loved him, and he loved his family. He loved his work and his patients,” Elsie shares. “He was a man who lived from the qualities of the soul—he was kind, caring and compassionate.”

“We miss him,” says Blazer. “It would be nice to have him here, especially at this moment in history. I just feel like we could certainly use his wisdom right now.”

Susan Gallagher is the Director of Communications for the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences in the Duke University School of Medicine.