Climate Change and Health

Health experts at Duke University School of Medicine are scrutinizing the myriad ways in which shifting environmental conditions, from sweltering temperatures to severe storms, shape our well-being.

In university laboratories, North Carolina homes and on the coastlines of faraway places, they've learned not everyone is equally at risk. Their efforts involve pinpointing solutions to help those susceptible to environmental disruptions, which could affect respiratory and cardiovascular health, food security, infection resilience, and mental health.

“As health care providers look at any number of health conditions, most are impacted by climate change and the environment,” said Robert Tighe, MD, a lung expert and newly named leader of the School of Medicine’s climate research strategy. “We’re surrounded by the environment every day and changes are bound to impact our health.”

Tighe, a professor of medicine with a secondary appointment at the Nicholas School of the Environment in the Division of Environmental Science and Policy, has long researched what makes some individuals more vulnerable to lung injury and disease. But he’s distinguished himself as a researcher working to identify factors and pathways involved in the body’s response to environmental pollutants like ozone, wood smoke, and silica -- dust found in sand, gravel, granite and rocks.

Nearly every school and department across Duke University is engaged in addressing climate change, including top researchers at the School of Medicine who are working to understand the health issues that have emerged and intensified from a changing planet.

Unraveling the Mystery of Lung Cancer in Non-Smokers

Climate change could impact the risk for lung cancer, even for those who have never smoked. Cases of non-smoking associated lung cancer have nearly doubled from 8% in 1990-1995 to 15% in 2011-2013.

Tomi Akinyemiju, PhD, a population health and cancer researcher at Duke School of Medicine, is examining how exposure to radon, a colorless, odorless gas found in rocks and soil and released during extreme temperature and precipitation, might contribute to these trends and alter lung cancer risk over time.

Everyone is exposed to some level of radon. The question is not if you are exposed to radon, but how high is your level of exposure? Akinyemiju leads a team of Duke researchers working on the Climate Impact on Lung Cancer Via Exposure to Radon (CLOVER) project. They are leaving no stone unturned.

Researchers are examining climate-related environmental and behavioral patterns to assess the risk of radon exposure. This involves asking North Carolina residents “Do you keep your windows open when it’s hot?” or “Do you live in the basement or on the first floor?” which can impact access to fresh air. Demographic data shows racial disparities in radon gas awareness, with Black residents and those in low-income neighborhoods less likely to be aware of or test for the invisible threat.

It's unclear how extreme precipitation and heat due to climate change may increase radon. There's also more to discover about how our responses to climate change, like spending more time indoors or using air conditioning more frequently, affects radon exposure and, in turn, the risk of lung cancer.

Radon-associated lung cancer can be prevented by limiting exposure to radon in indoor air. Findings by the CLOVER researchers could be translated to policy, potentially adding radon testing to building codes and requiring landlords to test for radon on their property.

A collaboration with North Carolina health officials has played a crucial role in advancing the Duke research by providing free radon tests to check indoor air.

Food Fight: Madagascar Rethinks Agriculture and Nutrition

Food is a basic necessity of life. Climate change, though, is forcing us to rethink what we eat and how we grow it. One place this is already being acutely felt is in the SAVA region of Madagascar, recognized as the capital of vanilla.

A team led by JJ Strouse, MD, PhD, associate professor of medicine at Duke School of Medicine, and James Herrera, PhD, Duke Lemur Center-SAVA Program Coordinator, are working to gain a better understanding of how climate change affects food security in Madagascar.

Part of this work includes learning about the people in Madagascar – what they prefer to eat, how they grow their food, how much food they have access to, and how their diets influence their overall health.

With a focus on children and women of childbearing age, Strouse and team gathered basic anthropometrics from people in the SAVA region – height, weight, arm circumference, and a noninvasive measure of hemoglobin to screen for anemia. “We found some prevalence of anemia, stunting, and children being underweight,” Strouse said. “There was relatively low food diversity, but people were open to considering other agricultural practices.”

Rice, for example, is a staple food source in Madagascar, but it takes a lot of water to grow. Climate models predict that while the area will receive the same amount of rain per year, it will be concentrated into shorter rainy seasons, creating more flooding. The dry season will be longer, creating more droughts. All of this makes for tougher conditions for growing rice.

Herrera, who lives in Madagascar nine months of the year, works with a team to conduct workshops on climate-smart agriculture. They lead workshops with local communities about drought tolerant crops, how to harvest rainwater, and hold cooking classes to show how to make heathy and tasty meals with more easily available foods. This not only helps people adapt to cultivating potentially better crops, but also improves their diet diversity and nutritional health.

"We are able to follow up with these communities month after month," Herrera said, "to measure how nutritional heath and farm productivity change after they've adopted climate-smart techniques."

The team is starting, literally, from the ground up, which gives communities a vested interest in their food and overall health. “If you want to drive behavioral change,” Strouse said, “you need to include the community and let them drive change.”

Tracking Mental Health Storms

As temperatures climb, so can tempers, and it's no secret that heat waves can fuel aggression and violent crime. But as climate change churns up more hurricanes, the storms can also bring a flood of emotions, according to research by Rajendra A. Morey, MD, a psychiatrist and professor of psychiatry and behavioral health at Duke School of Medicine.

He studies brain changes associated with post-traumatic stress disorder, and after reading “An Uninhabitable Earth,” he turned his attention to an area that’s just beginning to be researched: the interconnectedness of climate change, displacement, and mental health.

Data from the U.S. Census shows 2.5 million people were forced from homes last year because of extreme weather. Such events are bound to trigger despair. The stress could be ongoing as hurricane seasons lengthen, meaning months of worrying if the next storm could wash away a home and livelihood. Among those living in Florida’s Miami-Dade and Broward counties, Morey’s 2021 study found an increase in symptoms of depression, anxiety, and PTSD following major storms. Wildfires are also scorching homes, jobs, and psyches.

“You can’t stockpile mental health services,” Morey said. “But alongside efforts to rebuild infrastructure, economy and provide medical care, we should be including mental health services in our disaster responses.”

Climate Change Heats Up Fungal Threat

One of our best protections against fungal pathogens is our core body temperature, but fungal diseases are on the rise. Fungi grow best between 77 and 86 degrees Fahrenheit; however, global temperatures are rising, leaving researchers concerned that fungi will adapt to survive in warmer conditions.

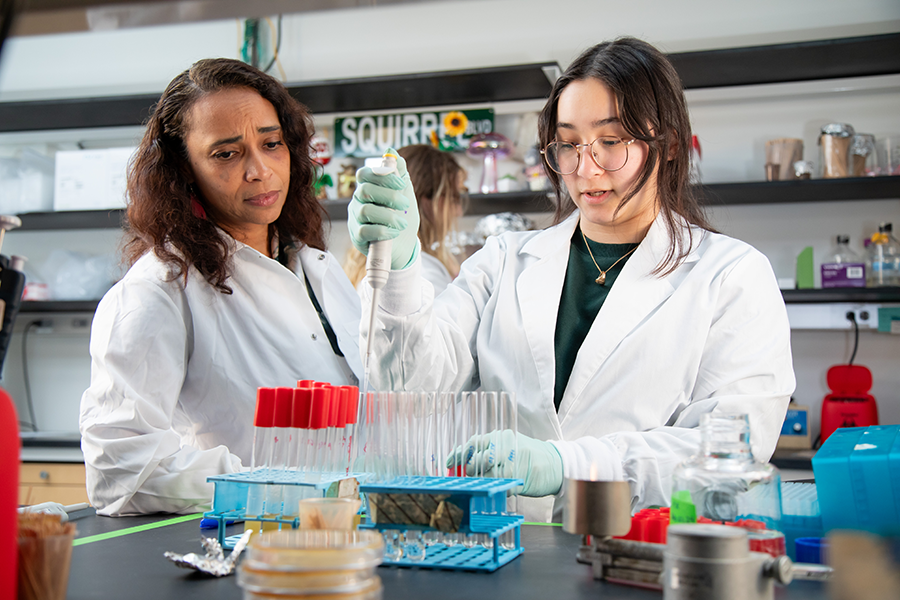

HBO’s “The Last of Us,” has brought more attention to the issue that’s being studied in the lab of Asiya Gusa, PhD, assistant professor of molecular genetics and microbiology at Duke University School of Medicine. She is exploring what happens to the fungus cryptococcus when it is forced to grow in warmer temperatures.

Cryptococcus is an environmental fungus found all over the world. Most humans who breathe in the spores are unaffected; however, for those who are immunocompromised or immuno-suppressed, coming in contact with Cryptococcus can make them seriously, even fatally, ill. It starts as a lung infection that can spread from the lungs to the central nervous system and into the brain, causing cryptococcal meningitis, which kills 110,000 people annually.

Gusa wants to know if heat stress causes the fungus to gain more virulent qualities, which could have a significant impact on human health.

“What we are worried about,” Gusa said, “is that increased heat and extreme weather events that disrupt the soils, increases the geographic spread of fungi, and gets more spores in the air."

Fungal pathogens are currently an underfunded area of research and few drugs are on the marketplace to treat fungal diseases. “We need to bring attention to the very real threat fungal pathogens pose,” Gusa said.

And the stakes are high. “There are no vaccines, and there are limited drugs because major drug companies have not been willing to invest in clinical trials,” she said. “We have poor diagnostic tools and poor surveillance, so we don’t have a good sense of the scope of the problem to be able to keep tabs on how it is changing over time.”

Flooded Homes, Venomous Snakes: The Race to Deliver Health Care

Climate-related disasters – extreme temperatures, windstorms, hurricanes, flooding, and more – are increasing, and as they do, so do their effects on human health.

Catherine Staton, MD, associate professor of emergency medicine at Duke School of Medicine, and her team are working to better understand the impacts climate change-related disasters have on human health while also empowering communities and providing better access to care, no matter where people live.

“Climate change disasters are dramatically increasing, and we’re going to need health systems that can handle that,” Staton said. “Through our partnership with Fundação de Medicina Tropical Heitor Vieira Dourado in Manaus, Brazil, specifically with health system resiliency in mind, we are working to understand how we can improve health systems to predict what problems may arise and how to respond.”

In Brazil, many communities are built along the Amazon River. Climate change has caused an increase in flooding events, with many communities facing daily flooding. The increase in water also creates another danger: more venomous snake bites.

“We started seeing that the human-animal interface – meaning snakes,” Staton said, “is different because of climate change.”

However, where snake bites are occurring and where anti-venom is located have historically been in two very different places. Snake bite victims sometimes have had to travel eight hours on multiple boats and vehicles to get access to anti-venom. Such a delay in treatment is not only painful, but it can also lead to lifelong complications and even death.

Instead of having all the anti-venom in the larger cities, Staton and team are building a decentralized model using a data-informed method to identify the best locations to get treatments closer to where the snake bites are happening. “If you improve services at the community health center level,” Staton said, “you improve access to comprehensive services.” This includes getting antivenom to places that provide vaccinations against other diseases and improving the transport network between the community health center and referral centers.

“Our research center, GEMINI- Global Emergency Medicine Innovation and Implementation Research Center, focuses on empowering people,” Staton said. “By giving them the training and the knowledge, we have given them the power to take action for their communities.”

Shantell M. Kirkendoll and Alissa Kocer are members of the Strategic Communications Team at the Duke University School of Medicine.