For millions living with nerve pain, even a light touch can feel unbearable. Scientists have long suspected that damaged nerve cells falter because their energy factories known as mitochondria don’t function properly.

Now research published in Nature suggests a way forward: supplying healthy mitochondria to struggling nerve cells.

Using human tissue and mouse models, researchers at Duke University School of Medicine found that replenishing mitochondria significantly reduced pain tied to diabetic neuropathy and chemotherapy-induced nerve damage. In some cases, relief lasted up to 48 hours.

Instead of masking symptoms, the approach could fix what the team sees as the root problem — restoring the energy flow that keeps nerve cells healthy and resilient.

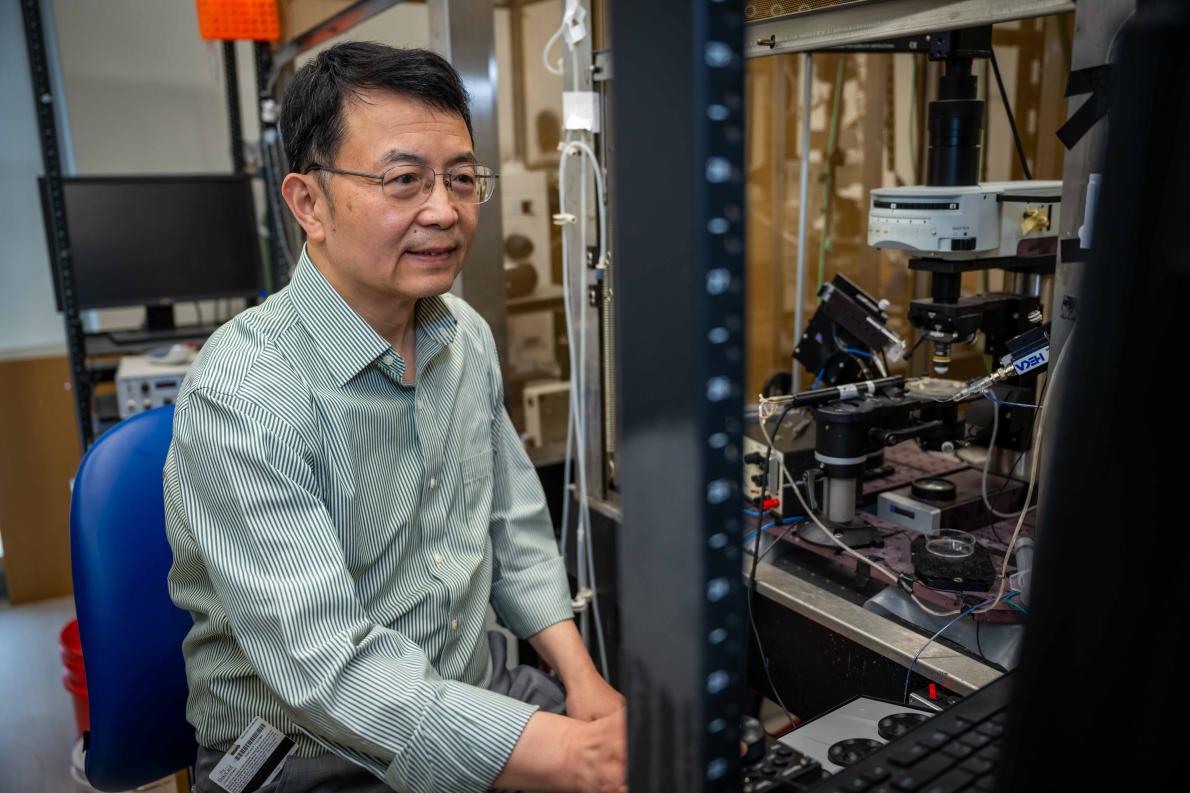

“By giving damaged nerves fresh mitochondria — or helping them make more of their own — we can reduce inflammation and support healing,” said the study’s senior author Ru-Rong Ji, PhD, director of the Center for Translational Pain Medicine in the Department of Anesthesiology at Duke School of Medicine. “This approach has the potential to ease pain in a completely new way.”

Their findings build on growing evidence that cells can swap mitochondria, a process that scientists are beginning to recognize as a built-in support system that may affect many conditions beyond pain.

The secret life of glial cells

Sensory neurons that detect touch or pain have extremely long branches — sometimes stretching three feet from the spine to the skin.

Keeping these far-flung nerve endings stocked with mitochondria is a constant challenge. When the supply falls short, neurons struggle to function and heal. Inflammation rises, pain circuits become overly sensitive, and people can develop neuropathy, a common complication of diabetes, as well as chemotherapy and nerve injuries.

The Duke team focused on satellite glial cells — the tiny support cells that wrap around sensory neurons in the dorsal root ganglia, a hub that sends touch, temperature, and pain signals to the brain.

They found that these glial cells can deliver mitochondria directly to neurons through tiny channels called tunneling nanotubes (TNTs). When this mitochondrial handoff is disrupted, Ji said, nerve fibers begin to degenerate — triggering pain, tingling and numbness, often in the hands and feet, the farthest stretch of nerve fibers.

Although TNTs have been studied for years, this is the first clear evidence that they work this way inside living nerve tissue.

“By sharing energy reserves, satellite glial cells may help keep neurons out of pain,” said Ji, a professor of anesthesiology, neurobiology, and cell biology at Duke School of Medicine.

Ji worked with lead author Jing Xu, PhD, a research scholar in the Department of Anesthesiology, along with longtime collaborator Caglu Eroglu, PhD, a Duke professor of cell biology known for her expertise in glial cell behavior. Eroglu’s lab helped to isolate mitochondria for transfer.

Boosting the natural energy exchange reduced pain behaviors in mice by 40-50% within a day, the study showed.

Then researchers tried a more direct approach. Injecting isolated mitochondria directly into the dorsal root ganglia eased pain for days, but only when the donor mitochondria was healthy. Samples from people with diabetes had no effect.

The team also pinpointed a key protein, MYO10, that helps build the nanotubes required for this energy exchange. When MYO10 was switched off, pain worsened, a sign that the protein is essential for moving mitochondria between cells.

How mitochondrial transfer affects disease

The work reflects a principle emerging across cell biology: that cells can share energy when under stress.

Scientists say that if they can boost or restore these energy exchanges, they may be able to help damaged cells recover and influence a wide range of conditions, from obesity to stroke and cancer.

In obesity, damaged mitochondria from fat cells fuel inflammation and metabolic dysfunction. In stroke, support cells donate healthy mitochondria to help injured brain cells recover. And in cancer, tumors “borrow” mitochondria to grow, spread and resist treatment.

More work is needed, the scientists said, including high-resolution imaging to confirm precisely how nanotubes help deliver fresh mitochondria to nerve fibers.

Even so, the findings highlight a previously overlooked communication pathway between nerve and glial cells that could treat chronic pain at its source.

Additional authors: Jing Xu, Yize Li, Charles Novak, Min Lee, Zihan Yan, Sangsu Bang, Aidan McGinnis, Sharat Chandra, Vivian Zhang, Wei He, Terry Lechler, Maria Pia Rodriguez Salazar, Cagla Eroglu, Matthew L. Becker, Dmitry Velmeshev, and Richard E. Cheney.

Funding: National Institutes of Health, Department of Defense and Duke Department of Anesthesiology helped fund the study with authors receiving additional support from the Paul and Daisy Soros Fellowship, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Michael J. Fox and the Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s Initiative, and Duke University Neurobiology Research Fund.