In 2023 the global temperature climbed to the highest on record since the industrial revolution, and in the United States, heat-related deaths doubled between 1999 and 2023.

These and other adverse effects of climate change often amplify risk for the most vulnerable groups, including the elderly, those with low incomes, and mothers and children, said panelists at the 2024 Duke Health forum, “Health & Equity: Environmental Awakening.”

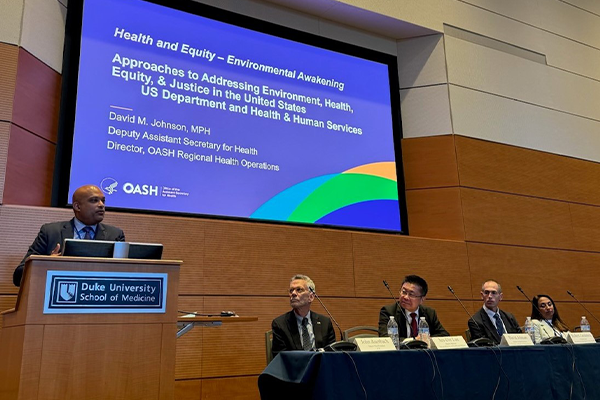

Held August 26, 2024, in the Trent Semans Center for Health Education, the forum featured a panel of distinguished speakers who compared and contrasted approaches to facing climate change in Taiwan and in the United States, with a focus on equity. The forum was moderated by John Auerbach, senior vice president of ICF.

In Taiwan, combatting climate change includes many forms of public education. Jen-Der Lue, deputy minister at the Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare, gave the example of a tailored public education project in Taiwan: a heat hazard prevention website for workers in high temperature outdoor operations that uses GPS positioning to track the heat index in real time.

“Climate change affects not only health, but livelihood,” Lue said. “One third of workers’ livelihoods are affected.”

In Connecticut, some of the most vulnerable people, such as those living in nursing homes, don’t have access to cool air, said Manisha Juthani, commissioner of the Connecticut Department of Public Health.

In addition, in Connecticut flooding events have created significant challenges with sewage backup in low-income neighborhoods. State health officials are working with local health departments to create new solutions, such as bringing health care into the community when flooding prevents people from traveling to hospitals, she said.

Adaptability is Key

Several panelists mentioned the need to leverage existing programs to direct resources to those most at risk from adverse effects of climate change. “The federal government has the ability to adapt current mechanisms to work for what is needed now for climate change,” said David Johnson, deputy assistant secretary, US Dept of Health and Human Services. “Medicare, for instance, through vouchers can cover air conditioning units for vulnerable populations.”

In another example, public health workers in Massachusetts incorporate climate change education when they conduct home visits for other reasons, such as lead inspections, said Robert Goldstein, commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. “This is part of building resilience,” he said.

In fact, Goldstein renamed his state’s bureau of environmental health to the Bureau of Climate Change and Environmental Health. This wasn’t just a symbolic change but refocused the department’s work to meet an urgent need, he said.

Tailoring messages

With some populations the term “climate change” isn’t effective, so educational messages may need to focus more on the impacts, such as increases in adverse weather or in diseases caused by vectors such as mosquitoes.

“Public health doesn’t often think about business, but we need to have business empathy, to think about who our consumer is. Do our policies and our messages resonate?” Johnson said.

The event was presented by the Duke Policy and Organizational Management Program and co-sponsored by the John Hope Franklin Center for Interdisciplinary and International Studies, the Office of Global Affairs, the Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, the Department of Population Health Sciences, and Duke Cancer Institute.

For more about climate change and health, watch EVP and Dean Mary Klotman's conversation with Robert Tighe, MD.