For too long, cancer treatment has been a double-edged sword – the very treatments designed to kill cancer cells often wrought havoc on healthy ones too.

But a new study published online Oct. 30 in Immunity, a Cell Press journal, unveils an approach to cancer treatment that researchers describe as more precise, long-lasting, and less toxic than current therapies.

The work, led by Duke University School of Medicine immunologist Jose Ramon Conejo-Garcia, MD, PhD, centers on the innovative use of IGA antibodies to target and kill tumor-promoting molecules, found deep within cancer cells, that have long eluded existing treatment options, including IGA antibody treatment.

“This is a proof-of-concept study, but the results are very promising,” said Conejo-Garcia, a Duke Science and Technology scholar in the Department of Integrative Immunobiology. “We believe that this treatment could be used to target a wide range of cancer mutations.”

Early experiments on mice with lung and colon cancer revealed notable reductions in tumor growth and minimal side effects.

The study focused on a particular type of antibody called dimeric IgA (dIgA). Its special structure allows it to target specific mutations linked with PIGR, a protein expressed on the surface of virtually all epithelial cancer cells and contributes to the growth and survival of cancer cells.

One such mutation, KRAS G12D, is a known instigator of the deadliest cancers. The study revealed that digA binds to rogue, mutated proteins then ushers them out of the cell in a process called transcytosis, stopping tumor growth.

LEARN MORE: Precision Cancer Medicine and Investigational Therapeutics

When tested in mice, the KRAS G12D-specific antibody was more effective at shrinking cancer tumors than current treatments in clinical tests. Small molecule treatments may have limited access to certain cancer cells, short-half lives, and come with side effects.

Researchers found similar results with another cancer mutation, IDH1 R132H, found deep inside cancer cells.

Scientists have struggled to target the mutated KRAS protein, but the new findings suggest the uniquely designed antibody can reach these intracellular molecules.

According to researchers, IGA antibodies have the potential for use as targeted therapy against stubborn mutations driving common, aggressive cancers, particularly epithelial cancers such as ovarian, skin, colon, cervical, prostate, breast, and lung cancer.

“This is a new way of targeting tumor cells by using an antibody that is exquisitely specific for point mutations or molecules that are truly tumor specific,” said Conejo-Garcia. “By neutralizing them and ensuring these tumor-promoting molecules are expelled outside the cell, we can halt tumor growth.”

Implications for cancer treatment

Throughout his career, Conejo-Garcia has researched ways to make our body’s defense system, the immune system, better at fighting certain cancers.

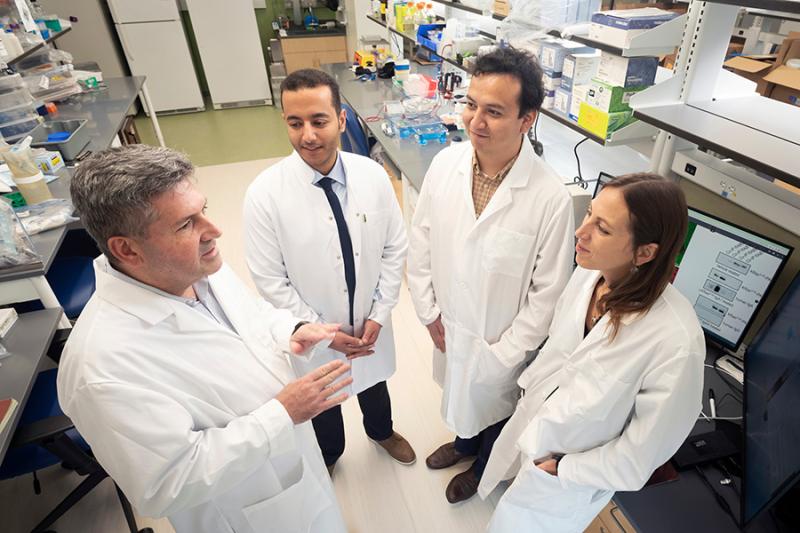

Conejo-Garcia worked on the current study with post-doctoral fellows Subir Biswas, PhD; Gunjan Mundal, PhD; and Carmen Maria Anadon, PhD, co-senior authors of the study, while at H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, and finalized the research after he joined the Duke faculty in 2023.

The results offer a glimpse of future cancer treatments that are more tailored, reducing harm to healthy cells and improving patients’ quality of life.

IGA antibodies are just one part of the innovative field of immunotherapy. Treatments like PD-1 inhibitors and CAR T-cells have shown unprecedented durable cancer remissions.

“The immune system is the only system in the body that has two key properties that make it ideal for cancer treatment: specificity and memory,” said Conejo-Garcia, a member of the Duke Cancer Institute. The immune system can specifically target tumor cells and it can also remember those cells to mount a more effective attack if the cancer returns.

Researchers are refining the antibody to make it easier to produce and administer to patients, with the aim of eventually testing it in clinical trials.

Additional authors: Richardo A. Chaurio; Luis U. Lopez-Bailon; Mate Z. Nagy; Jessica A. Mine; Kay Hanggi; Kimberly B. Sprenger; Patrick Innarmarato; Carly M. Harro; John J. Powers; Joseph Johnson; Bin Fang; Mostafa Eysha; Xiaolin Nan; Roger Li; Bradford A. Perez; Tyler J. Curiel; Xiaoping Yu; and Paulo C. Rodriguez.

Funding: This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health R01CA157664, R01CA278907, R01CA124515, R01CA178687, R01CA278907 and U01CA232758 to JRCG; K99CA266947 to SB; R01CA184185 to PCR; K08CA231454 to BAP; and CLIP Award from the Cancer Research Institute to JRCG. Additional support was provided by Moffitt Cancer Center, the government of India’s Department of Biotechnology and the Ovarian Research Alliance.