Second Year Student Blog: Reilly Walker

"What is grief?"

During a Grand Rounds lecture called Grief 101, Dr. G posed this question to a silent room. Not a single word popped into my mind to describe this feeling, though I had known it for the past two years. Instead, my stomach sank as I was transported back to that hospital room, where I stood alone, gowned in full PPE, hearing the last beep of the ventilator as I told the nurse it was okay to take my father off life support, days after he was declared brain dead. Grief, I realized, is not easily translated into words; it's a visceral experience that transcends language.

I tried to bring my attention back to the lecture, and still, no words came to mind. Instead, I found my mind back in PA school interviews, being asked, “What is the biggest challenge you have overcome?” I remembered the many times I cried to strangers while summarizing the experience of suddenly losing a parent just two months prior. Interviewers moved swiftly to the next question, only deepening my confusion, anger, and loneliness.

Grief had robbed me of a major part of my support structure and became my new normal. I remembered preparing to move away from my friends and worrying about how difficult it would be to connect with a class full of strangers.

Grief is exhausting, I whispered to myself in that lecture hall.

Focusing back on the slideshow in front of me, I saw the quote: "Acknowledgement — being seen and heard — is the only real medicine for grief."

This brought to mind my interview with Betsy Melcher, a PA faculty member at Duke, whose response stood apart from the rest. After sharing my story, she paused, offered a moment to step away if needed, and simply thanked me for opening up. At the time, I couldn't pinpoint what made her reaction stand out. When she later became my advisor and provided invaluable support throughout my journey with both grief and PA school, I realized it was her empathy and that her advice came from her own experience. Through her, I learned the value of vulnerability in fostering genuine connections.

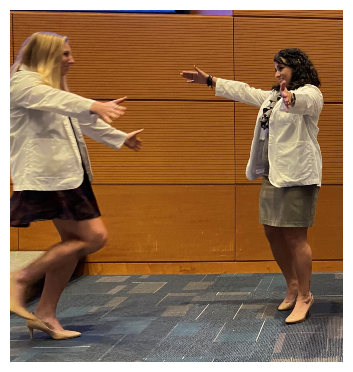

I thought back on the day of my White Coat ceremony, when I ran off the stage into a big embrace from my classmate Adriana. Hours earlier I followed her out of our palliative care lecture, where we wiped each other's tears affirming to each other that we would make it through the rest of the day even though we were both missing loved ones.

I thought of how I cried in the bathroom on my first day of my first clinical rotation, Emergency Medicine, after I got a call that my aunt (whom I felt closest to after my father passed) had just taken her last breath.

Grief is cumulative…

Every second of that shift, I worried about how I could manage going to the funeral and supporting my family while still meeting clinical hours.

Grief is overwhelming…

“Is it supposed to be? I still ask myself to this day. Is that what makes you re-evaluate what is truly important?

The field of medicine often prioritizes productivity, fostering a culture that idealizes the compartmentalization of hardship - which may be why I didn't think twice about how I would take care of myself during that shift. Will they see my grief as a weakness? I wondered. Fortunately, they did not. My advisors encouraged me to take time off until I felt “ready,” demonstrating that grief needs both time and acknowledgment. Classmates delivered food, cards, and study resources and gave me their shoulders to cry on.

While time is important, grief has no timeline. It may have a beginning and a middle, but I cannot speak to an end - unless the end is that it is just learning to live with grief.

I remembered the pit I felt in my stomach on my first day back after taking some time off from clinical rotations, but also the relief I felt when I was greeted with a smile and a hug from Ashley, a PA I shadowed once before. Feeling welcomed, I eventually told her I was having a tough first day back and was met with empathy, affirmation, and her own vulnerability, telling me how she experienced grief at a young age, too. Moments like this underscored the importance of building support networks, reminding us that we do not have to navigate grief alone.

Much like misery, grief seems to love company.

Bringing formal recognition to grief is crucial in medical settings, which can sometimes feel emotionally sterile. Fortunately, Dr. G and others at Duke actively acknowledge and address this issue. I emailed Dr. G after he finished his Grief 101 lecture and told him how touched I was by his attempt to try to put the vast topic of grief into an hour-long lecture. I highlighted how I've observed his guidance reflected in the actions of providers throughout Duke. Prior to his lecture, I thought I might be the sole observer of the subtle nuances of dealing with grief as a provider—like the gentle tone during end-of-life discussions, the sincere eye contact, the handwritten notes to families, or the extra check-ins after long shifts. Now I understand that others who know of grief see it too. Whether experienced personally or professionally, education on grief undeniably fosters positive change.

Grief is recognizing the little things that bind us all.

I now laugh at myself, realizing I had agreed to write a “Navigating Grief'' blog, only to finish it by noting grief is not something we navigate around, but instead, it is something we are forced to face head-on. My intention in sharing this is to shine a light on the importance of community in healing, thank those at Duke for fostering such a beautiful community, and let any pre-PAs in a similar position know that it is possible. Let us not shy away from the pain of others but instead offer our light and love to guide them through dark moments and grow stronger by sharing these experiences.

For those experiencing grief:

- Allow yourself to feel your emotions fully, without judgment or guilt.

- Seek support from friends, family, or professional counselors who can offer understanding and empathy.

- Remember that healing takes time, healing is not linear, and it's okay to prioritize your well-being over academic or professional demands.

- Practice self-care activities such as journaling, listening to music, exercising, or engaging in hobbies that bring you joy.

For those supporting someone who is grieving:

- Listen actively and without judgment, allowing the grieving individual to express their emotions freely. Understand that grief is a healthy, common, ubiquitous theme in life.

- Offer practical support such as helping with daily tasks or providing a comforting presence.

- Validate their feelings and experiences, acknowledging the validity of their grief.

- Check in regularly and offer ongoing support, especially after the immediate crisis has passed.

My line is always open. Feel free to reach out reilly.walker@duke.edu

Reilly Walker is a second-year student the Duke Physician Assistant Program. Email reilly.walker@duke.edu with questions.

Editor’s note: Duke Physician Assistant Program students blog monthly. Blogs represent the opinion of the author, not the Duke Physician Assistant Program, the Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, or Duke University.