Mouse lemur genomes shed light on climate as a driver of speciation

Sure, lemurs are adorable. With their big eyes, some even look like they belong in a Disney forest. But that is definitely not what drives Anne Yoder’s passion to research these primates. She is interested in them at a genomic level.

Yoder, the Braxton Craven Distinguished Professor of Evolutionary Biology, arrived at Duke from Yale in 2005 and transformed the Duke Primate Center into the Duke Lemur Center (DLC), making it a powerhouse of research and a world leader in the study, care, and protection of lemurs. She stepped down as director in 2018 to focus on finding answers to some of her big research questions.

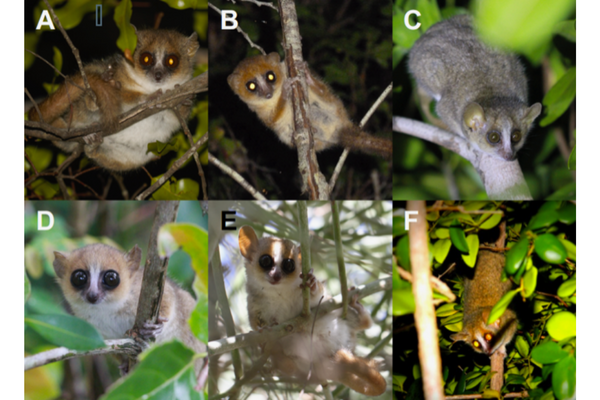

When Madagascar broke off from Africa some 88 million years ago, it became isolated from the rest of the world and turned into a biodiversity hotspot as plant and animal life evolved to adapt to the land. Now, more than 10,000 named plant and animal species are endemic to the island, lemurs included. And yet, an untold number of species may still be unrecognized because even though they are biologically distinct, there are no observable clues to reveal their differences. In other words, they are what biologists refer to as "cryptic species."

Yoder is, in her words, obsessed with cryptic species. “Cryptic species occur all across the tree of life,” she said, “and it’s not until you go in and look at their genomes that you understand that they are really different organisms.”

Which is exactly what Yoder did recently when she investigated a contact zone between the gray mouse lemur and the reddish-gray mouse lemur. She and her colleagues set out to investigate the genomes of presumed hybrid individuals found in previous research that used microsatellite data, tracts of repetitive DNA commonly used for forensic investigations and paternity tests.

Yoder's group took a different approach, conducting genome-scale research with a RAD-seq approach, which uses enzymes that cut and tag the genome for sequencing, to determine who was mating with whom to create these supposedly hybrid mouse lemurs.

But they found something else entirely.

Instead of finding evidence of hybridization, they found that every individual that had previously been identified as a hybrid with microsatellite data was actually one or the other "parental" species — a big surprise to scientists who have assumed that animals that look alike and act alike must certainly be the same thing.

No matter how much they looked like each other or how close they lived next to each other, the gray mouse lemur and the reddish-gray mouse lemur were reproductively isolated. “If you have the opportunity to breed and you don’t, then you must be a different species,” Yoder said. “We see that these mouse lemurs have become separate species in the blink of an eye, with respect to evolutionary timescales.”

So what is causing this rapid speciation?

The answer, in all likelihood, Yoder says, is climate change. While the northern hemisphere saw glaciers both retreating and advancing during the Pleistocene period, also called the Ice Age, the southern hemisphere went through cycles of cool, dry periods and warm, wet periods.

“In geological time, they cycled quickly,” Yoder said. When it was cold and dry, forests contracted. When it was warmer and wetter, the forests expanded.

“We think the mouse lemurs were naturally separated by climate change and forest retreat, and they became isolated from each other for some period of time,” Yoder said. “Once they had the opportunity to reconnect, evolution had happened.”

Mouse lemurs are therefore valuable indicator species. Given their capacity for rapid speciation, their geographic presence, absence, and abundance can inform researchers like Yoder how environmental and climate changes — both natural and anthropogenic — affect the biological condition of an area.

For example, Yoder's group has taken a special interest in the island's iconic grasslands. It has long been assumed that these grasslands were something humans created when they arrived on the island 2,000 years ago.

“The classic perception is that Madagascar was forested all the way north to south, east to west, and then humans arrived and destroyed the landscape,” Yoder said, “But our research, along with that of others, has shown that the grasslands are actually a natural feature of Madagascar. So the question becomes how much have they expanded because of humans, and how much that has affected the wildlife.”

To further explore the mechanisms driving all this cryptic speciation, Yoder and her DLC collaborator, Marina Blanco, recently received a four year, $1.4 million grant from the National Science Foundation, which they will use to sequence whole genomes of at least five lineages of mouse lemurs. “We really want to try to find out what is going on with their genomes to see if that is what’s driving all this rampant speciation,” Yoder said, “or if it’s pre-zygotic barriers, like singing different songs or having different smells.”

Sam Hyde Roberts, a field postdoc collaborating with Yoder and Blanco, has been live-trapping mouse lemurs all over southeastern Madagascar and taking small ear clips or skin biopsies. Along with new genomics postdoc Carolina Segami, Yoder's lab is eagerly awaiting the first batch of biological samples from the field, which will arrive in early February. “Until we have the corresponding genomes characterized,” Yoder said, “we have no idea who has been sampled, and until we know that, where they are living.”

With DLC postdoc Lydia Greene, Yoder and Blanco will also use some of the NSF grant money to build upon and expand genomic workshops in Madagascar for Malagasy scientists and students. Yoder's outreach to Malagasy scientists began more than 20 years ago thanks to her long collaboration with American conservation biologist Steve Goodman from Chicago's Field Museum. It was Goodman's ecology training program for Malagasy students that introduced her to the promise of supporting the academic community in Madagascar.

“It has been one of the most fulfilling activities of my career,” Yoder said, “and it still drives a lot of what I think about.”