Duke Medical Students Bridge the Classroom with Community Through Root Causes

It is a typical Friday at the Duke Outpatient Clinic on Roxboro Street. Sunshine gleams off of the red brick building, and the faint buzz of afternoon traffic can be heard nearby. Patients arrive steadily, for a weekly scheduled education session known as “Root Causes,” founded and implemented by Duke medical students. Today’s lesson: Getting savvy with diabetes.

People shuffle in using canes, walkers, or wheelchairs. Some have below the-knee amputations—evidence of a years-long battle lost against rising blood sugars and vascular damage. All of the patients—whether diabetic or not—have been referred to the program by a physician who believes they can benefit from the interactive discussions about healthy eating.

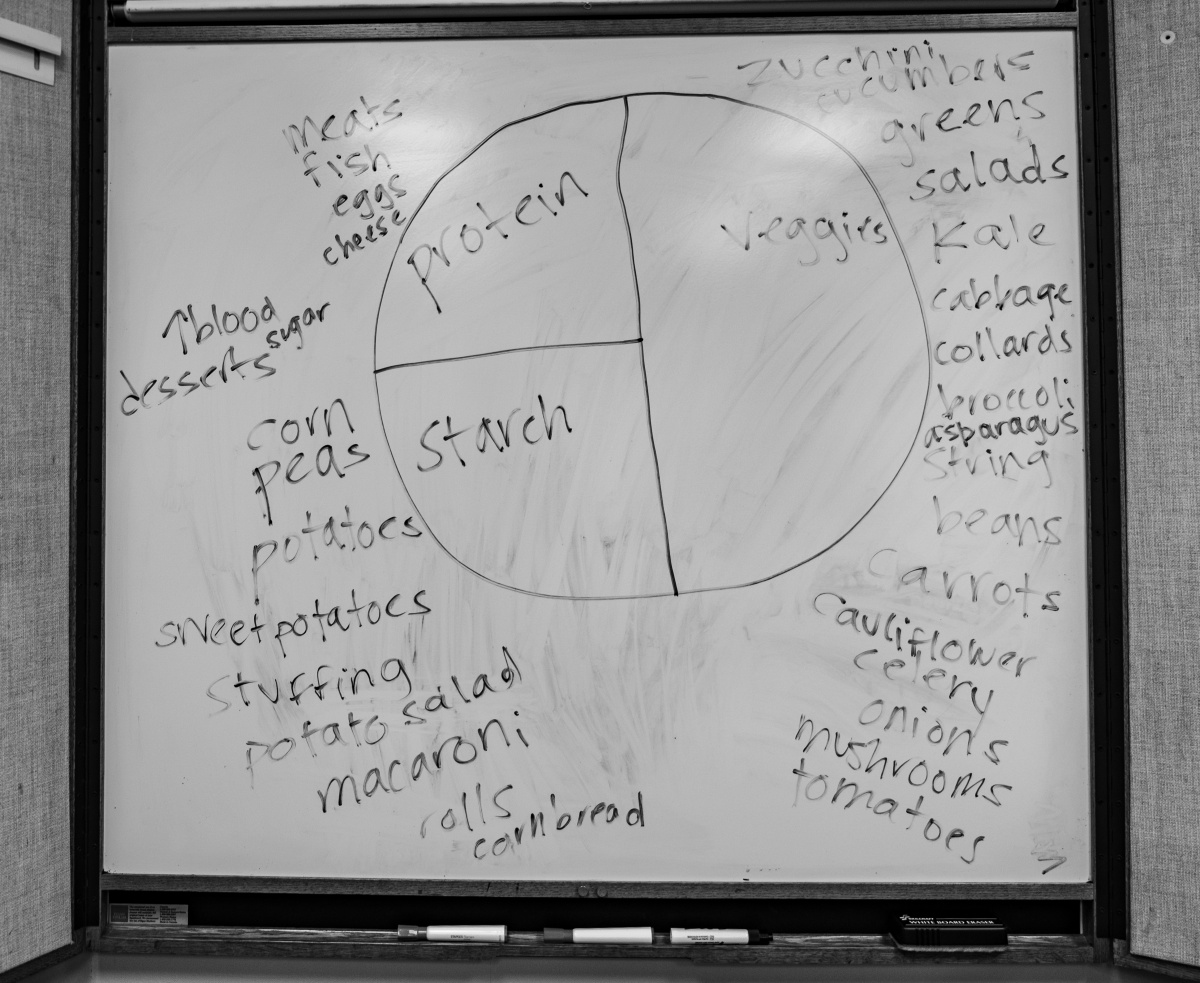

On this particular day, the focus is on how a healthy diet can lessen the effects of diabetes.

Clinical nurse specialists and registered dietitians explain how sugar affects bodily systems. If present at high levels, glucose induces cascades of chemical reactions in the blood that damage organs and vasculature throughout the body. In diabetes, the body’s sugar control system, headlined by insulin production in the pancreas, malfunctions, leading to high levels of blood glucose. Like many diseases, there is a genetic component at play. But far and away, type II diabetes is influenced by one thing above all—diet.

When a patient’s blood sugar is on the rise, physicians intervene early with suggestions of daily exercise and diet modification because often a change in lifestyle is enough for some to stave off the development of diabetes entirely. But many providers know that their suggested lifestyle modifications, particularly when it comes to dieting, may be unrealistic. For some patients, the decision to consume unhealthy foods is not a matter of free choice, but a matter of price.

A 2016 Durham County Community Health Assessment Survey of country residents identified cost and time as the biggest barriers to eating healthy.

In planning programming for Root Causes, medical student leaders at Duke have used the results from the survey, which are described in detail in the 2017 Durham County Community Health Assessment, a report produced by the Durham County Public Health Department, Duke Health, and Partnership for a Healthy Durham.

“This is how one of our patients puts it: ‘you can eat healthy, or you can eat more than once,” says Julian Xie, a fourth year Duke medical student. “It’s obvious that a nutritious diet is important for good health, but for people living in poverty, high food prices, unreliable transportation, and living in food deserts and swamps makes getting healthy food a daily struggle.”

“Food deserts,” or areas with no reliable access to grocery stores, and “food swamps,” or areas where unhealthy foods are more easily accessible, can be found across the United States including in Durham, according to the Food Access Research Atlas produced by the United States Department of Agriculture. The map shows a dense localization in Durham’s low-income neighborhoods.

Many health care providers and social workers in Durham try to identify patients at risk of food insecurity, but, “in most places, they have limited knowledge and capacity to improve patient food access beyond referral to outside agencies. Whether a patient can actually use a service they’re referred to is uncertain too - because of inconsistent hours, eligibility requirements, and the need for additional transportation,” said Willis Wong, a second year Duke medical student.

“We started Root Causes in 2017 because we wanted to create a student organization space that would support the engagement of health professional students in service, education, and advocacy relating to the social drivers of health,” said Xie, one of Root Causes founding members. “A lot of what we do is all about shifting the patient care paradigm to make things like healthy food a direct part of care provision.”

The group of Duke medical students who built Root Causes from the ground up— Julian Xie, Peter Callejo-Black, Christelle Tan, Spencer Chang, and Jackée Okoli— learned this lesson early. They were inspired to establish and legitimize their organization as quickly as possible.

The team wanted to follow models like that of Boston Medical Center’s Preventive Food Pantry, a hospital-based pantry that serves food insecure patients referred to their program by a full-time dietetic technician, said Xie.

Similarly, UNC has a hospital-based food pantry that serves patients identified as food insecure, meaning that they lack reliable access to a sufficient quantity of affordable, nutritious food. And other clinics address patient food insecurity by providing food vouchers that can be spent at local farmers markets or grocery stores.

The Duke student team approached Sarah Armstrong, MD, professor of pediatrics in the Duke University School of Medicine, to be the faculty advisor for the program, and she agreed. Later, in 2019, Patrick Hemming, MD, assistant professor of medicine, specializing in Internal Medicine, took over as the program’s advisor.

“Everyone in student leadership works so hard,” said Dr. Hemming. “I was so impressed by all of the initial data they’d already collected, which ended up winning them best poster presentation at the North Carolina Chapter’s of American College for Physicians annual meeting."

Fresh Produce

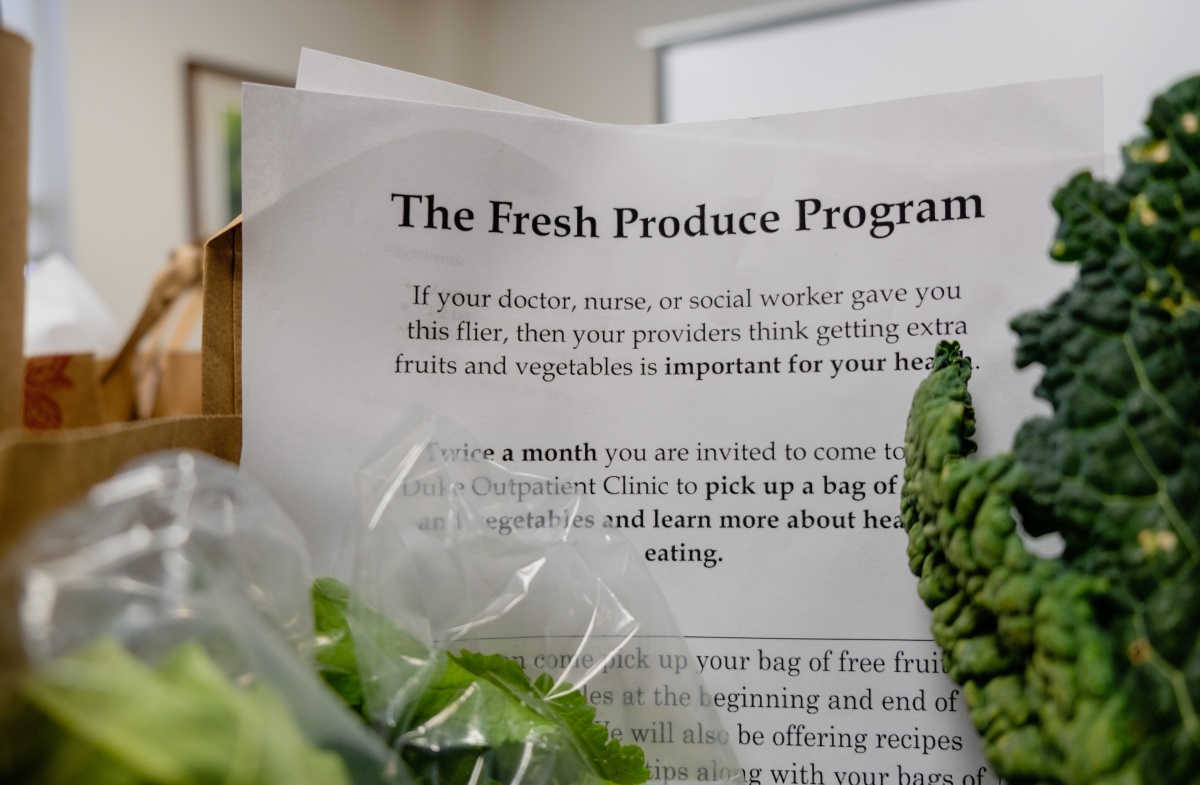

Amongst the various programs and events organized by Root Causes, one of the most well-attended is the Fresh Produce Program, or FPP, a bi-weekly program that distributes fruits, vegetables, and other nutritious grocery items to patients at the clinic on Roxboro Street.

The program serves adult patients seen at the clinic, as well as children and their families at the Duke Children’s Primary Care Clinic on Roxboro Street.

To qualify for the program, adults are screened by their physicians or clinical social workers using a 2-question Unites States Department of Agriculture tool :

- Within the past 12 months, we worried whether our food would run out before we had money to buy more.

- Within the past 12 months, the food we bought just didn’t last and we didn’t have money to get more.

Once identified as a patient at-risk of food insecurity, patients are connected with Root Causes and encouraged to attend the food distribution events. Given the association between food insecurity and metabolic syndromes like diabetes, distributions are strategically timed to take place directly after diabetic educational events.

“I’m a diabetic, so I go to the DOC [Duke Outpatient Clinic] 2-3 times a year for check-ups. I was talking to my doctor, and she told me about the program on Fridays—it’s a great program,” said patient Joseph Clayton. “It helps people from all different ethnicities, and it doesn’t discriminate; even some people who don’t meet the criteria in being diabetic, they can still get food if they need it.”

Food distributions events increased and continued to attract patients from 2017 to late 2018. But, around this time, the leadership in Root Causes identified a problem—some patients had never eaten the fruits and vegetables that were now being distributed. They were sometimes apprehensive to try the new foods, and many did not know how to prepare the food to eat.

“You can provide people with fresh produce, but people without time or understanding can easily have all of that food go bad,” said Dr. Hemming. “Patients need to be excited to eat new foods, if they try something, don’t like it, and are still hungry, they are still going to eat that big bag of Cheetos.”

That’s where Clayton came in. In addition to being a patient, he is also a chef with more than 25 years of experience. Clayton and his physician contrived the idea of organizing cooking classes for patients in the Fresh Produce Program, with the goal of teaching them to prepare foods and limiting food waste as much as possible.

“It’s just harmonious,” says Clayton when describing the classes. “We get a bag of food with 7-12 items, and they really have nothing to do with each other. I’ll look through the bags, take it to the front of the class, wash everything, and make a plan. Then as I’m cooking, a volunteer will be writing recipes in real-time while I’m talking to the class. The following week, we’ll print them out and pass them out, so when patients see the vegetables again, they’ll know what to do with them. At the end, it’s a real live recipe that we’ve concocted.”

“In the beginning, a lot of people would come in and say, ‘I’ve never eaten asparagus, or I’ve never eaten cauliflower.’ But they would come to a class, and see how simple it is to prepare, and how tasty it is. I would have people coming back in two weeks saying, ‘That was so good!” remembers Clayton.

The Fresh Produce Program has created a close-knit community of patients, providers, and students, and Root Causes keeps track of how well they meet the needs of their patients.

“A lot of times we fill out this little survey,” says Clayton. “It will ask questions like “How often do you cook this food? Does it help you financially? How many meals are you able to make? How much of the food did you actually use?”

Root Causes uses the data from the surveys to direct spending and food supply for future distributions.

Annette Smith (patient), Christine Neville (patient), Julian Xie (medical student), Joseph Clayton (patient, food demonstration leader), Willis Wong (medical student),

Ahmed Hussain (undergraduate student), Christelle Tan (medical student). In front, left to right: Eleanor Senmes, (MD/PhD student), Elana Horwitz (medical student).

Durham and Beyond

Xie and Wong, president and vice president of Root Causes, respectively, are excited for the future of the organization.

“My personal goal is to become a leader in medicine that bridges partnerships between health systems and community organizations to rethink healthcare delivery and maintenance,” said Wong. “I think the way that we incentivize healthcare spending in the United States is not efficient and does not address the ‘root causes’ of why people get sick, especially from chronic conditions. I hope to be part of the conversation and action when it comes to creating novel healthcare structures that seek to bridge some of these issues by partnering with various health-focused entities outside of the clinical setting.”

In addition to Durham-based initiatives, Root Causes has historically been involved in state level work in nutrition based initiatives. In 2017, members of Root Causes met with North Carolina state lawmakers to advocate for the Healthy Corner Stores Initiative, which provides funding and assistance to convenience stores that sell healthy foods. That year, the North Carolina State Assembly included a $250,000 allocation of funds to the Healthy Corner Stores Initiative.

For now, in Durham, Root Causes continues to impact the community. It is one of many initiatives Duke Health faculty, staff and students are involved in that aims to bridge equality and improve patient outcomes and quality of life.

For patients, the impact is tangible.

“One patient told us, ‘My HbA1c went from 7.7 to 6.3 and I lost 19 pounds!’” said Wong. HbA1C is a measure that physicians use to monitor blood-glucose control. A value greater than or equal to 6.5 is defined as a diabetic HbA1C by the American Diabetes Association.

“Another patient says that she has tried a lot of new fruits and vegetables, and she really appreciates having the recipes, so she knows how to make the new meals. She also said her kids and grandkids are trying new foods and are enjoying them. It’s improving the health of the whole family. This is a patient who’s had a lot of chronic health conditions and a lot of stressors in life and I think having the program as a positive ritual she gets to experience has been great….and her blood sugars are improving too!”

With a myriad of hard data to show that patients are satisfied and benefiting from the program, the organization has used their successes to apply for, and win financial support from sources like the Duke Green Grant Fund.

When asked about his fondest memory with his time so far with the Fresh Produce program, Dr. Hemming says: “What I really, really like to see is this group of medical students in there on Friday afternoons in their t-shirts and jeans smiling and chatting with patients. I think that’s the most tangible thing for me—seeing smiles on both sides and seeing the interactions. There is so much optimism and it feels great. And there is so much room to grow.”

Jackie Dillon is a second year medical student at Duke University School of Medicine.

All photos taken by Duke undergraduate student Sophia Li.