Women's Health: It's Personal for Nimmi Ramanujam

The night before she was scheduled to speak to more than a hundred Duke students, colleagues and at least one Nobel laureate, Nirmala ‘Nimmi’ Ramanujam got cold feet.

She had given countless talks before, many about the pocket colposcope, a device her team invented to bring life-saving access to cervical cancer screening to underserved regions. But this talk would be different. Ramanujam, the Robert W. Carr, Jr. Distinguished Professor of Biomedical Engineering and a professor of Pharmacology and Cancer Biology in the School of Medicine, was supposed to share her personal story as part of a special event highlighting the role of immigrants in the research enterprise.

In the days leading up to her talk, she toyed with slides about her childhood in Malaysia, her Southeast Asian heritage, and the parallels between her life and that of the famous mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan, who not only shared her last name but also belonged to the same caste of Brahmins, the upper echelon of Indian society inhabited by scholars and priests.

“I created a deck of slides that was all about me, but I couldn’t present it,” she said.

While the other six scientists presenting that day told the story of their lives, Ramanujam talked about her students, many of whom were immigrants themselves. “I had to talk about something orthogonal, because I couldn’t share my journey,” she said. “It’s like I made it up the elevator, and I wasn’t sure I wanted to take anyone back down the elevator with me.”

A view from the top

Despite being raised at the top of Hindu society, Ramanujam’s prospects were limited by her gender. She had to cover her arms and plait her thick dark hair. She couldn’t leave her bedroom or touch elderly family members when she got her menstrual period. And she was constantly told that she wasn’t as smart as her brothers.

“I grew up with this whole idea that I didn't have anything meaningful to say,” she recalls. “People told me I wasn’t very good at academics. But I knew I was good at music, so I focused on that.” She became so good at playing the veena, a South Indian instrument resembling the sitar, that she often performed on the radio with her mother, a talented musician.

As she came of age, her father began plotting arranged marriages. Her mother, a closet intellectual who had never been able to pursue any interests outside the arts, suggested their daughter get a higher education instead. When Ramanujam was just 16, they sent her to the U.S., where she went to the University of Texas at Austin, to pursue a degree in engineering, just as her brothers had.

“It was traumatic to come from that place of complete oppression, to this place where the first things you see are McDonald's and alcohol, and you're a vegetarian who’s never had a drink before in your life,” she recalled. “But then there were elements that I could connect with immediately, like music. It was something universal, and relatable.”

At the time, the airwaves were dominated by pop stars like Blondie, Pat Benatar, and Madonna, who sang of women’s empowerment but also embodied the excesses of the late 1980s. Ramanujam struggled to fit in to her new world, and her grades suffered. “I didn’t understand anything,” she said. “I was really a poor student – and I hated engineering.”

Then, just as Ramanujam was gaining her footing toward the latter part of college, she was diagnosed with carcinoma in situ in her cervix, a breast lump, and an ovarian cyst, all in quick succession.

She was more fascinated than frightened by the experience – it helped to be a naïve teenager. “It was the first time in my life that I knew what it was like to have my reproductive health scrutinized and intervened upon.”

She realized technology could be personal, and that a career in health care could give greater meaning to her engineering studies. Though her college advisor scoffed that her grades weren’t good enough for her to get into graduate school, she kept showing up at his office hours to plead her case, and eventually convinced him to make a case for her.

Twenty-five years later, as the Robert W. Carr, Jr. distinguished professor at Duke University, in the second highest ranked biomedical engineering program in the U.S., Ramanujam still has an aversion to grades. She doesn’t give exams in her classes and relies more on interviews than transcripts when hiring students into her program. She doesn’t even pay attention to the impact factor of the journals she publishes in, instead gauging success by how much she is able to change the status quo through the lives of those she is affecting.

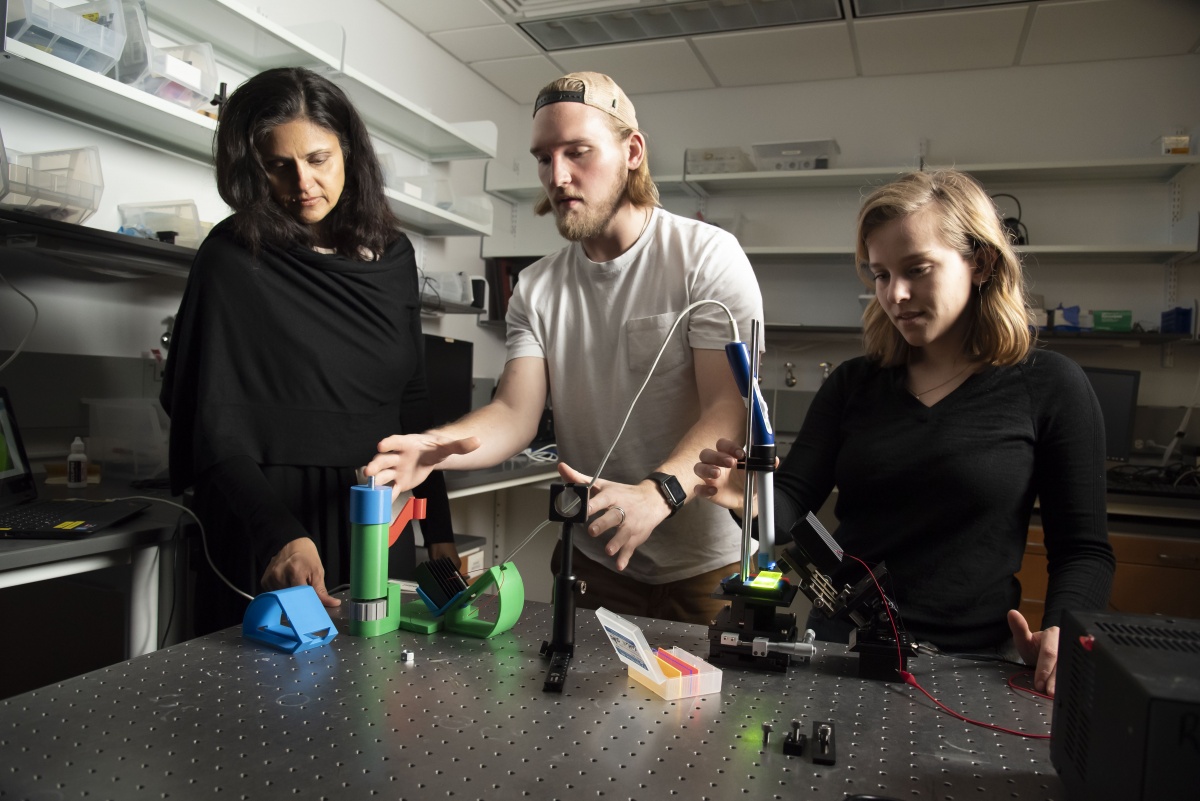

“Nimmi always talks about impact,” said Jenna Mueller, who has worked with Ramanujam for the last ten years as a Ph.D. student and now as a postdoctoral associate.

“She has a bird’s-eye view, and then she can zoom in to the tiniest detail and know what is happening with the science. I think her vision is unparalleled in how she pushes the boundaries of what biomedical engineering is.”

Precision and art

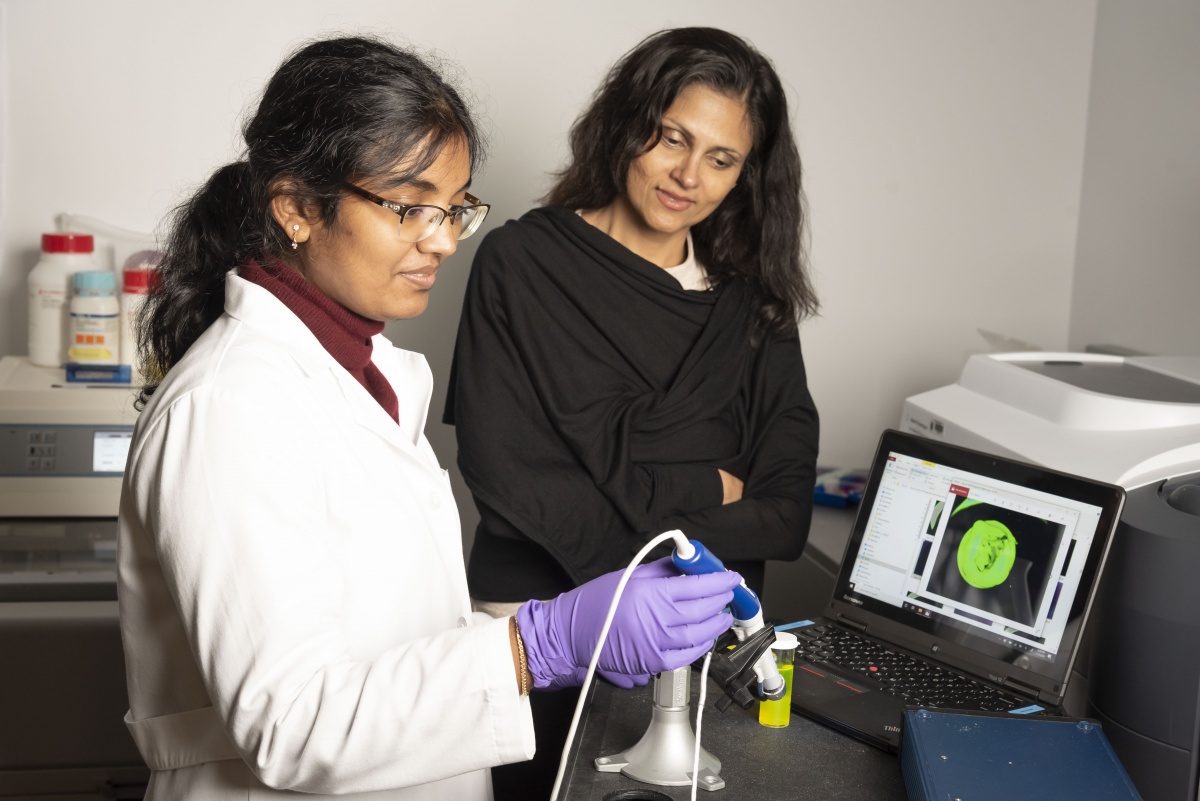

Her research team’s pocket colposcope is one of those status quo-changing, boundary-pushing innovations.

A clinical colposcope, the device used to diagnose cervical cancer costs upwards of $15,000. This high price and a centralized approach to screening and diagnosis is one reason that 85 percent of cervical cancer deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries.

Screening is also painful, since it requires the use of a speculum, a primitive device for prying open the vagina to gain a view of the cervix. For centuries, the speculum has remained relatively unchanged. Archaeologists found an instrument that looked eerily similar to one while excavating the House of Surgeons in Pompeii. James Marion Sims, the father of gynecology, made the last major improvements to the device, testing it on enslaved women living on his property in Alabama, during the 19th century.

“We are a product of our culture,” said Ramanujam. “The devices we use are designed by people – men primarily – with a certain perspective. When I looked at the evolution of gynecology, I realized that the colposcope is so expensive because it uses optics that have to be far away from the cervix. It’s designed like a telescope, because physicians didn’t want it to go close to the vagina and get dirty.”

Ignoring that antiquated notion, Ramanujam designed a camera that could be sent directly into the reproductive tract to take pictures of the cervix up close. The idea was simple enough, but the execution proved anything but. Ramanujam’s team tried inflating balloons in the vagina to open it up. They designed versions of silicon menstrual cups with tiny cameras embedded. For a time, they focused on a particularly promising model that looked like a tampon applicator that opened its petals like a flower when its handle was turned.

Ramanujam took the device home and tested it on herself. As designed, the petals unfurled and latched onto her cervix. But then they wouldn’t come off. “I thought, “Oh no, I’m home alone having this medical emergency!””

Finally, the device broke and released its hold on the more delicate parts of her anatomy.

“That got the wheels in motion and I realized we couldn’t have moving parts breaking inside the body,” she said.

Several iterations later, her team arrived at their current design, which also drew inspiration from a flower, this time the tube-shaped calla lily, hence referred to as the Callascope. The device’s asymmetry gently tilts the cervix for its close-up, and it works as well as the standard $15,000 model but at a fraction of the cost. Plus, it doesn’t require a speculum. (An earlier version, the pocket colposcope, can be paired with a speculum for practitioners hesitant to change).

It was the perfect convergence of precision and art, born of Ramanujam’s extreme life experiences. “I can remember every little fact because of my rules-based upbringing, but I can also be creative because of the musician that lives inside of me,” she said. “For me, my life from the time I was back home to here has been a very stark contrast. I think about how some of those things I resented as a child have been among my greatest assets now.”

The next generation

Jose Jeronimo, an obstetric gynecologist and chief technical officer at the Global Coalition Against Cervical Cancer, met Ramanujam six years ago. He had just finished giving a talk on women’s health at the NIH when she came up to him to tell him about her very first design of the pocket colposcope and the Callascope, peppering him with questions about how to make it viable. Before long, he had agreed to partner with her to help develop the device and bring it to the developing world.

One time, Jeronimo traveled with Ramanujam’s team to Peru to get feedback for yet another round of improvements. The health workers in the rural community they visited were so excited about the new device that they begged the researchers to leave it with them. “We had to explain to them that it was just a prototype, and there was more work to be done,” he recalled.

Thus far, Ramanujam and her team have collected data on more than 1,000 women in eight countries, including the U.S., India, Kenya, Tanzania, Honduras, Zambia, and Peru. Jeronimo says Ramanujam succeeds where others fail because she always has the ultimate goal in mind.

“You can be a genius and develop some beautiful device, but if you don’t know what is happening in the developing country where the device is supposed to be used, it won’t work,” he said. “Nimmi is able to listen, and adapt, and come up with something people see the value in.”

Over the years, Ramanujam has gotten several offers from companies looking to commercialize the device. She’s turned them all down, instead choosing to do everything at Duke, all the way up to getting FDA approval. She has involved her students in every step of the development process, which she says teaches them the humility and resilience it takes to succeed in technology innovation.

All photos by Les Todd.

Recently, Ramanujam created a company, called Calla Health, with one of her former students serving as CEO. She also applied for a $100 million MacArthur grant, proposing a revolutionary new way to deliver health care for cervical cancer that places women at the center of the solution.

Her mentees, like Jenna Mueller and Marlee Krieger, often stay connected to her long after their term would typically end. Krieger, who is now executive director of Ramanujam’s Center for Global Women’s Health Technologies, has been working for Ramanujam for 14 years, ever since she met with her about an opening in her lab.

“I believed after interviewing with her that she was interested in improving the lives of women everywhere, and that meant not only internationally in low-resource communities but also right here within her center.”

Ramanujam believes that technologies come and go and that her most enduring legacy will be the people she touched. She says she is most fulfilled by empowering her students, mostly female, to use their voices to spur social change. And she continues to encourage young women, especially her teenage daughters, to use their voice to advocate for themselves and others.

“I want my kids to exercise their opinions, be strong-willed, and have strong ideas,” she said. “I feel the same way about my students. Because if they’re thinking outside the box, they can’t be oppressed. We can quell people's confidence very easily if we're not careful. I try extra hard to believe that people are capable of so much more than we believe.”

mentees inspired by Ramanujam.

Marla Broadfoot is a freelance science writer and editor living in Wendell, NC.

Les Todd is a Durham-based freelance photographer specializing in higher education and medicine.