We Are What We Breathe

When Duke pulmonologist Rob Tighe, MD, thinks about the biggest effects of climate change on society, polar bears, barren crop fields, and underwater beach houses are not the first images that come to mind. Instead, Tighe, a pulmonologist and associate professor in the Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, and Critical Care Medicine in the Department of Medicine at Duke, thinks about the health of his patients.

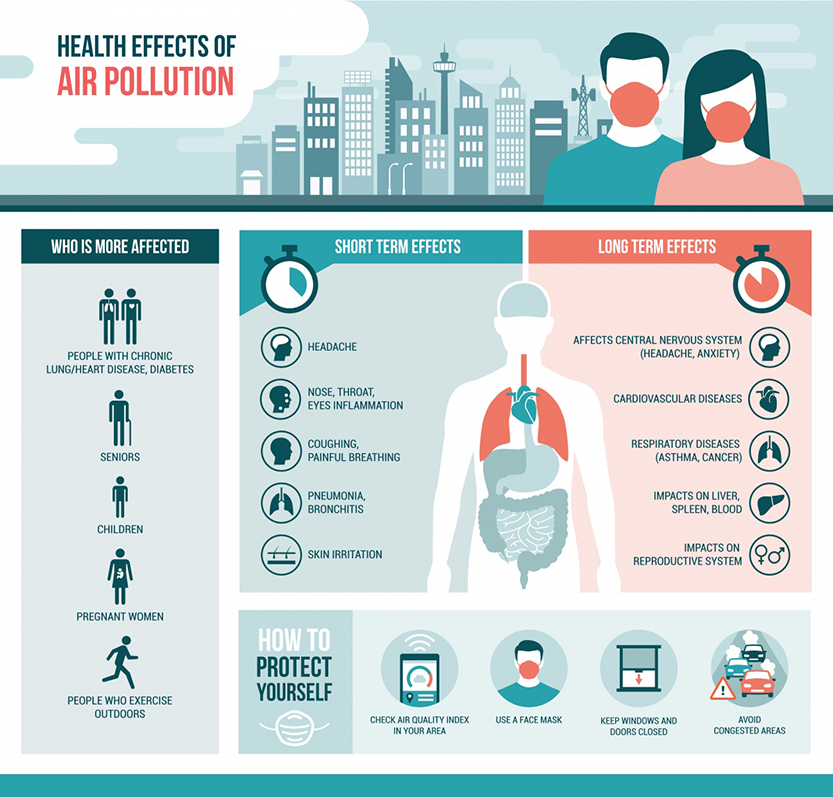

Tighe especially worries about his patients with severe chronic lung disease on “code red” days which indicate particularly high levels of ozone. Ozone is a particulate that forms when sunlight hits chemicals from combustion sources like cars, stoves, or industrial facilities. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) which monitors air quality for the entire United States using its Air Quality Index, issues code red alerts for specific locales when it detects high ozone amounts in the air. People with asthma, lung disease, and heart disease have been shown to be especially at risk for acute episodes on these days.

“It’s very consistent,” said Tighe. “Usually 24 to 72 hours after a spike in air pollution, we notice a spike in emergency room visits for acute exacerbations related to chronic lung disease, asthma, or heart attack.”

The worst part, he said, is that air pollution is only expected to get worse. The Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change (IPCC) which includes more than 1,300 scientists from the United States and other countries, predicts a temperature rise of 2.5 to 10 degrees Fahrenheit over the next century.

Although the temperature rise may seem miniscule, it’s enough to have a significant and lasting effect, leading to loss of sea ice, accelerated sea level rise, and longer, more intense heat waves. These changes will affect humans in a number of ways, including food security, extreme weather events and wildfires, and diseases transmitted by insects, food, and water. But perhaps the most acute way, said Tighe, is through decreased air quality.

“It’s really troubling to think about the impact that climate change is having and will continue to have on air pollution and therefore the health of patients most impacted by air pollution,” said Tighe. “In addition to critical mitigation efforts to reduce air pollution, we need to identify those people who are most susceptible to its adverse effects.”

As a physician-scientist, Tighe spends just as much time in the lab as he does in the clinic, researching the chronic lung diseases he treats to better help his patients. Recently, he started an informal networking group of faculty members across campus who conduct research in the area of air pollution and human health. Participants in the group hail from the School of Medicine, the Nicholas School of the Environment, Pratt School of Engineering, Sanford School of Public Policy, and various institutes across campus. The group looks for ways to collaborate on research projects, address outreach opportunities in the local community, and further student education in environmental health issues through joint mentoring. Tighe’s ultimate goal is to establish an environmental health center within the School of Medicine.

“Similar to the phrase ‘you are what you eat’, we are what we breathe,” said Tighe. “It is critical to understand how exposures in our environment impact our health and to identify the unique groups that are susceptible to these effects. This will require coordinated effort across the university to tackle these important problems.”

Personalized Medicine To Combat Air Pollution

Research has long shown that people with lung and heart disease are especially susceptible to ozone, which, when inhaled, aggravate the airway and generate molecules that disrupt normal functions in the lung and heart. But are there other diseases or factors that make a person especially susceptible to air pollution, and if so, what are they? Members of Tighe’s newly formed environmental health working group are working to find out.

So far, researchers in the Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, and Critical Care Medicine in the Department of Medicine in the School of Medicine have identified several at-risk groups: those with diabetes, obesity, and those who are genetically predisposed to asthma. The sexes also have a different response to ozone pollutants with males developing airway hyperresponsiveness—or ‘twitchy’ airways as seen in asthma patients—and females simply developing an immune response. More research is needed to determine this distinction’s clinical relevance.

“Understanding the specific biological factors make a person susceptible to air pollution will help physicians prescribe better, more personalized treatment plans for patients,” said Loretta Que, MD, a pulmonologist and professor in the division who sees patients who are obese and who also have asthma. She’s interested in understanding whether air pollution is a factor in explaining why obese individuals have more severe asthma symptoms.

Stavros Garantziotis, MD, adjunct associate professor of medicine and medical director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Institute’s Clinical Research Institute, treats patients who have asthma. He researches the genetic factors that make a person at risk for developing asthma, and how air pollution, particularly ozone, increases that risk. “If patients were more aware of their risk on code red days, and knew to stay inside during these days, countless lives and dollars related to healthcare costs could be saved,” said Garantziotis.

When working with asthma patients, Garantziotis seeks to develop a personalized exposure profile by asking them about their daily habits and lifestyle. Then, he works with the patient to identify ways that they could alleviate adverse effects from air pollution, whether that be staying inside on hot days, wearing a mask, using an air purifier in the home, prescribing to certain medicines or diets, or even re-locating.

“It usually doesn't have to go as far as moving, thankfully, at least not in this part of the world,” said Garantziotis. “There are certainly other cities and countries in the developing world where it's well known that pollution can actually be highly damaging and might support a move. But in this country, you don't have to do that. There are other ways to mitigate exposure and often times we see a pretty significant, very dramatic effect on the severity of the asthma.”

Patty Lee, MD, chair of the Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, and Critical Care Medicine has been very supportive of the work of Tighe, Que, and Garantziotis. Lee is an internationally recognized expert in environmental stressors, such as oxygen toxicity, cigarette smoke and, most recently, infections, and their effects on lung immunity and lung-vascular aging.

“The lungs serve as a biologic intersection between our external and internal environments, therefore during my tenure as the division chief of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine I am exceptionally committed to studying the impacts of climate change and air pollutants on health and disease,” said Lee.

Learning from Colleagues in Other Fields

When developing an environmental health working group, Tighe knew that an interdisciplinary approach was imperative. Environmental scientists, engineers, and policy makers have long studied the impacts of climate change, perhaps even before most physicians became aware of the dangers.

Duke has been a leader in environmental health research for many years. In the 1980s, the Nicholas School of the Environment launched the Integrated Toxicology and Environmental Health Program, a network of interdisciplinary faculty and graduate students devoted to environmental health research. A facet of the program in is the NIH-supported University Program in Environmental Health, which provides support for doctoral students to conduct environmental health research.

At the Duke Global Health Institute, researchers have long studied the connection between air pollution and human health, as many countries, such as India, China, and Brazil, have faced its impacts for years. Jim Zhang, PhD, professor of global and environmental health in the Nicholas School of the Environment and the Duke Global Health Institute, has linked high air pollution in China to lower birth weights and cardiovascular disease.

Meanwhile, the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering in the Pratt School of Engineering has faculty specifically focused on environmental health engineering, and the Sanford School of Public Policy has faculty working to address examine the formation and impacts of public policies with a focus on providing solutions to environmental problems.

“Duke is unusual in having great Schools of Medicine, Environment, Public Policy, and Engineering, as well as a Global Health Institute, all doing work in the area of air pollution and health,” said Joel Meyer, PhD, associate professor of molecular and environmental toxicology in the Nicholas School of the Environment and the Duke Global Health Institute. “This provides a remarkable opportunity to integrate research from sources of pollution, to exposure and mechanisms of health effects, to medical, engineering, and policy solutions. But for this to happen, someone has to take the lead in bringing people together. We are lucky that Rob is doing that, and I am thrilled to be part of it.”

Lindsay Key is the senior science writer in the Duke University School of Medicine and editor of the online storytelling magazine Magnify.