Unraveling the Mystery of Migraines

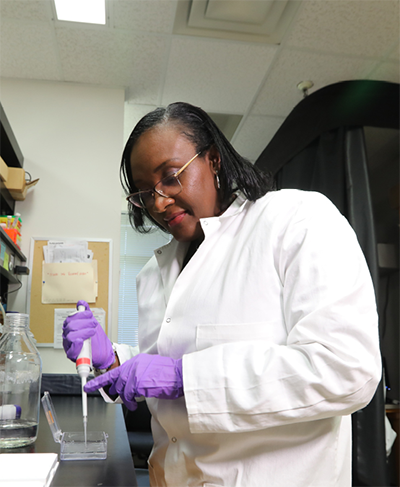

Carlene Moore’s infectious, bellowing laugh helps offset the serious nature of the work underway in her lab at Duke University School of Medicine to study painful conditions -- from sunburn and migraines to trigeminal neuralgia, a severe facial condition so painful it is known as the “suicide disease.”

Moore, an assistant professor in neurology and member of the Duke Institute for Brain Sciences, has spent the past 15 years studying pain.

Initially Moore focused on how skin pain, like sunburn, gets communicated from the epidermis to the brain. But because of Moore’s own debilitating bouts of head pain, or cephalgia, as it’s referred to clinically, her lab has changed course to search for ways to dampen the pain stemming from a condition that’s “more than just a headache.”

More than 1 billion people worldwide suffer from migraines, making it the most common neurological disease and third most common illness. But little is known about what kickstarts a migraine.

Part of the problem is that it’s a tricky thing to nail down. “Migraines aren’t just one thing,” Moore said. “In addition to head pain, they are accompanied by other symptoms such as nausea, vomiting and sensitivity to sound and light.”

Migraines unfold across several phases, making them complicated to catch at the onset, and they present differently in different people. “Unlike foot pain, you don’t know where the point of origin is for a migraine.”

Another complicating factor is who migraines predominantly affect: women. Three out of four migraine sufferers are female, but historically most migraine research was done by male scientists using male research animals, namely rodents.

“We’ve been studying male mice almost exclusively up until recently,” Moore said. As of 2016, researchers receiving federal funds from the National Institutes of Health must now include both sexes in their research (or have a strong justification for excluding one sex). In a relatively short time, the policy has had a large effect.

“It has opened up the field,” Moore said. “Different sex-dependent mechanisms of pain have already been discovered.”

Historical limits aside, researchers like Moore have worked out a few elements involved in generating migraines. The first key ingredient is the face’s “everything sensor,” the trigeminal nerves. These nerves collect all the sensory information from your forehead to your chin and everything in between and send it to your brain to be processed. But to tell you that the coffee you sipped is too hot or that your cheek hurts from being slapped, it needs an interpreter.

That translator is a family of transient receptor potential (TRP) channels that relay information about the outside world, like taste, temperature, or touch, and code it in an electrical language that the brain understands. TRP channels stud the trigeminal nerve cells, making them a critical step along the way of propagating migraine pain.

“We are interested in understanding the mechanism and function of TRP channels,” Moore said. “Especially in migraine and how we could develop new therapies for migraine.”

Smoothing wrinkles and easing pain

One surprising way Moore and others have figured out how to silence TRP channels is Botox, the muscle-paralyzing toxin commonly used as an anti-wrinkle therapy.

Botulinum toxin, a neurotoxin better known as Botox, is often injected into the forehead. Anecdotal reports in the early 2000s suggested people receiving Botox for its cosmetic effect were relieved to be both wrinkle- and migraine-free after the treatment. This, Moore explained, inspired further investigation and in 2010 approval from the Food and Drug Administration to use Botox as a treatment for chronic migraine.

While it offers great relief, Botox for migraines is a lot like acupuncture. “It’s a series of 31 injections in a single session performed every three months,” Moore said. “You definitely feel it!”

She would know. Moore has received Botox to alleviate her own migraines and prescribed it in the lab to a dish of trigeminal nerve cells from mice. Although Botox has been an approved migraine treatment for over a decade now, it’s still not fully understood how and why it works.

Recent work from Moore’s lab in collaboration with the pharmaceutical company AbbVie has revealed some of the very first cellular snapshots of how Botox blunts head pain from migraines.

“When we bathe the cells in an inflammatory soup, we see that Botulinum toxin is preferentially effective in the pain-sensitized cells,” Moore said.

Once in the nerve cells, botulinum toxin appears to dampen the pain signal by snipping a tether-like molecule called synaptosome-associated protein 25 (SNP25). This protein helps release packets of neurochemicals and receptors, like TRPV1 and TRPA1, in brain cells.

By interrupting the docking process, Moore thinks Botox helps prevent the TRP channels from being embedded in trigeminal nerve cells, and therefore there are fewer interpreters to convey pain signals to the brain.

Family ties

These are still early days for Moore’s migraine research, but outside the lab, she and her family have a long history with painful conditions.

Moore grew up on the Caribbean island of Saint Kitts as the second eldest of five girls. Her father was a welder at the island’s sugar cane factory, and her mother was a school cook. From a young age, her parents recognized Moore’s curiosity.

“I’ve always been a very curious person,” Moore said. “I can still hear my mom saying how inquisitive I was. I’d question everything about nature. I’d question everything about what's going on. I just always had a question, like, ‘What is that?’”

Moore’s inquisitive nature led her to her current curiosity about pain, starting in elementary school when her mom was diagnosed with a debilitating herniated disc.

“She was the one who got me interested in the neuroscience of pain.” Moore said. “When I was around 9 or 10, she developed a slipped disc, and had terrible, terrible back pain. I watched my mother suffer with pain all her life.”

Falling in love with research

Since Saint Kitts is a small island with limited medical facilities, Moore’s mom had to travel to England for spinal repair surgery, leaving her five daughters behind for six months while she recovered. That led to the beginning of Moore’s second familial encounter with pain.

Moore is the second oldest of five girls but was tasked with being the big sister during her mother’s absence because her older sister was often incapacitated by migraine pain. In fact, all but Moore’s youngest sister experience migraines.

Moore continued to focus on science with pain in mind as she continued her schooling in Saint Kitts with the aspirations of working in medicine. “I only thought of science as leading to being a nurse or doctor back then,” Moore said.

While working on her bachelor's degree in biology from Midwestern State University in Texas in 2001, Moore had another life-changing experience: a summer research internship at the University of Texas at Austin.

“It was my first lab immersion and I fell in love with research,” Moore recalled. “Asking questions and actually getting to answer some of the questions within the day kind of opened my eyes to the world of research,” she said. “Up until that point, I just thought that if you're interested in science and biology, probably the main way to go is medical school.”

Her internship led her to both a new career path and a commitment to passing opportunities forward to the next generation of scientists.

“Internships are really important, which is one of the reasons I mentor summer high school students through the Duke University Neuroscience Experience,” Moore said. “I want to give young people the experience that I received, because I know how important and how impactful my summer internship was.”

The internship convinced Moore to switch from a medical school track to neuroscience and earn her doctoral degree in neurobiology from the University of Alabama at Birmingham in 2008.

Moore then came to Durham to work as a postdoctoral researcher in the lab of Duke neurology professor and physician Wolfgang Liedtke, MD, PhD. “I wanted to recruit someone who was ambitious and shared the enthusiasm to do something challenging with the chance to make a bigger discovery,” Liedtke said. “And that's when I met Carlene and sealed the deal.”

Under Liedtke’s guidance, Moore had a productive science time as a postdoc, including a landmark discovery of how to make a better ointment to treat sunburn pain using TRP antagonists.

“If somebody is really good at something, it looks effortless,” Liedtke said of Moore’s skills as a scientist and ability to work with and mentor others. “It's like watching Roger Federer playing tennis.”

Moore says part of her success running her own lab is due to the lessons she gleaned from Liedtke’s compassion and ability to “see people as more than just scientists.”

“It's tough when you're trying to meet deadlines,” Moore said. “As a junior faculty, there is a tenure clock, and so much pressure to produce. But you have to remember that the people you’re working with are people with lives. Yes, we need the data, but it will always be needed.”

Headaches and hormones

Armed with hunches about the origin of migraine pain, Moore is on to new scientific challenges. She is embarking on several new projects focused on humans in collaboration with physicians at Duke Health (including her own personal migraine doctor of 15 years).

One project Moore recently submitted for a grant with Duke pediatric neurologist Klaus Werner, MD, PhD, and Timothy A. Collins, MD, chief of headache and pain in the Department of Neurology, aims to improve treatment for teenagers with “nearly daily persistent headaches.”

Moore is also studying the grimly nicknamed “suicide disease,” or trigeminal neuralgia, a chronic pain disorder that leads to excruciating face pain, as well as exploring the connection between migraines and eye stroke, which can be mistaken for a migraine but potentially lead to vision loss if ignored.

Most exciting to her is a new project looking at why two out of every three women with migraines report menstrual cycle-linked migraines.

“We’ve started some of the work in our lab at a basic level by looking at the role of sex hormones like progesterone, estrogen, and even testosterone on TRP channel regulation,” Moore said. “My hypothesis is that just before the onset of menses, sex hormones play a role in inhibition of TRP channel signaling. However, just before menses when hormone levels drop drastically, some of that inhibition goes away, leading to more pain.” Further experimentation is needed to test this and other hypotheses.

Moore is busy to say the least, even when she’s continuing to weather her own migraines.

She describes herself as a “functional migrainer.” When she has a migraine, she cannot stand still. Bright computer monitors make the pain worse. To cope, she often busies herself in the lab, slowly working toward better migraine treatments, while riding out another wave of throbbing head pain herself.

Dan Vahaba, PhD, is the director of communications at the Duke Institute for Brain Sciences.

Photography by Jim Rogalski, senior video and multimedia producer in the Duke University School of Medicine Office of Strategic Communications.

Main photo: Carlene Moore, PhD, is an assistant professor in neurology at Duke University School of Medicine who studies pain from sunburn to migraines.