Rewiring the Cannabis-Addicted Brain

The “munchies” are a common cultural punchline, but for Duke University School of Medicine clinical neuroscientist Tonisha Kearney-Ramos, PhD, they signal a deeper issue. With chronic cannabis use, natural appetite fades and users may eat only when under the drug’s influence.

More than 19 million Americans show signs of cannabis use disorder (CUD) — cravings, withdrawal symptoms, and difficulty quitting. Nearly 30% are young adults, aged 18 to 25.

As access to recreational and medical cannabis grows across the country, so does the need for treatment. But existing options—like cognitive behavioral therapy and contingency management—often fall short.

“If you come to see me in my clinic for cannabis use disorder, I don’t have much with a solid evidence base to help you,” said Gregory Sahlem, MD, an associate professor in the Duke Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, who is trying to change that.

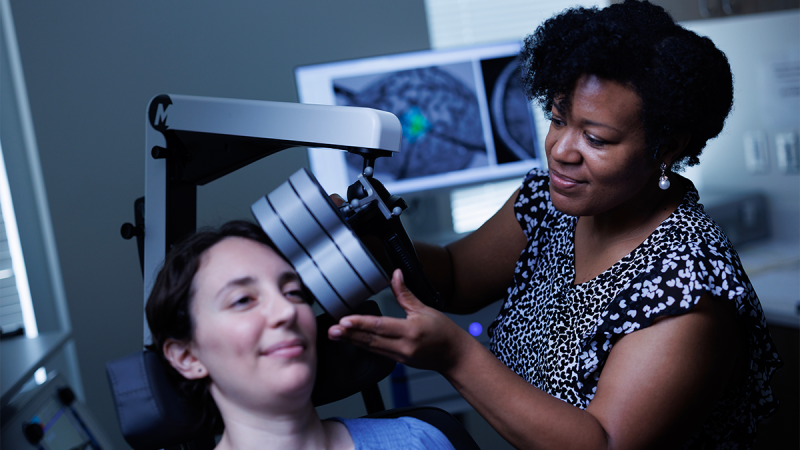

He and Kearney-Ramos, an instructor in psychiatry and behavioral sciences, have spent nearly a decade exploring a new option: using targeted magnetic pulses to retrain the cannabis-addicted brain.

No, It’s Not Harmless—and Yes, It’s Addictive

Despite its laid-back reputation, cannabis can cause lasting damage. It affects memory, learning, and sleep, and increases the risk of stroke and heart disease. Smoking it harms the lungs. And it has also been linked to anxiety, depression, and schizophrenia.

About one in 10 cannabis users will develop CUD, or patterns of CUD like spending a lot of time using cannabis and giving up important activities in favor of cannabis use. The risk climbs higher for those who start using cannabis before age 18 or consume products with high levels of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the chemical that delivers the high.

THC potency has increased in recent decades, from about 4% THC in 1995 to about 16% in 2022, with some online dispensary products hitting far higher levels.

The Duke researchers’ work focuses on repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, or rTMS, a noninvasive therapy that uses magnetic pulses to activate or suppress specific parts of the brain. It's been cleared by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment of depression, obsessive compulsive disorder, and tobacco addiction.

Here’s how it works: In people with substance use disorders, including CUD, brain networks that regulate reward, emotion, and self-control are disrupted. rTMS can stimulate underactive areas or quiet overactive ones, rewiring the brain back toward balance.

“We know all of these circuits are implicated in addiction, but we don’t know yet if they’re all abnormal in everyone with addiction, or if any given individual has one or more dysfunctional circuits,” said Sahlem, who is the only researcher with published clinical trials using rTMS to treat CUD. “We can actually target each of these networks with rTMS with precision and hope to be able to start to tease out what’s actually going wrong with a given individual.”

From First Trials to Real Promise

In 2016, while an assistant professor at the Medical University of South Carolina, Sahlem launched the first-ever clinical study of rTMS to treat cannabis addiction. Early results of the study were promising: it was safe, and participants reported fewer cannabis cravings.

Two follow-up trials, funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), tested different doses and schedules. As the research progressed, so did the results. A lighter treatment schedule, with less frequent sessions, kept more participants in the study, and many reported using cannabis less often, with some quitting altogether.

In his most recent study conducted at Stanford, Sahlem—who joined the Duke faculty in 2024—used brain scans to help precisely target two brain networks disrupted in addiction.

“We randomized people to receive rTMS on the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), which is part of the self-control network, or on the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC), which is part of the reward network,” Sahlem said.

Both approaches led to positive outcomes, but those who received magnetic stimulation to the reward network showed the biggest drop in cravings and drug use.

Kearney-Ramos, who joined the Duke faculty in March, has been a pioneer in targeting the brain’s reward network — an approach long overlooked in rTMS addiction research.

While most studies focused on boosting self-control, she found while working with alcohol users and cocaine users that quieting the brain’s reward system could lessen cravings — particularly in patients with strong responses to drug-related triggers, known as high drug cue reactivity.

But the key, she said, is personalization: for patients with low drug cue reactivity, the same treatment can backfire.

“High drug cue reactivity is predictive of drug cravings and use,” said Kearney-Ramos. “This is why it is really important to capture the brain’s state before we treat. It might predict what kind of therapy will work best for that person.”

After joining the faculty at Columbia University in 2018, Kearney-Ramos shifted her focus to CUD. That year, she authored a paper reviewing the state of rTMS research in people who use cannabis and proposed future directions for rTMS treatment development.

Around the same time, she received a NIDA-funded career development award to study an accelerated rTMS treatment protocol targeting the brain’s self-control network in people with CUD.

She’s now leading a study at Duke using an accelerated rTMS protocol, compressing a six- to eight-week treatment course into a single week. Participants’ brain activity is measured before and after treatment while cannabis use is tracked through mobile surveys that capture changes in their drug use and cravings in daily life.

On the Horizon

Beyond her current study, Kearney-Ramos has an eye on access.

“Advances in TMS technology have made it more effective, but also more expensive and complex,” said Kearney-Ramos. “That has meant the very patients who need it most, like those in low resource clinics or from underprivileged backgrounds, are often the least likely to get it. Right now, there’s been a trade-off between scientific progress and health equity in our field.”

Sahlem is awaiting a funding decision for a four-year, multiple site Phase 3 study involving 250 participants that could bring rTMS for cannabis use one step closer to FDA clearance. The trial will increase the number of rTMS sessions and extend the treatment timeline compared to previous studies.

If successful, it would be the largest trial of its kind and could offer much-needed treatment for millions of people.

Susan Gallagher is the director of communications for the Duke Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences.

Eamon Queeney is assistant director of multimedia & creative in the Office of Strategic Communications at the Duke University School of Medicine.

Daniel Dunston is a senior multimedia producer in the Office of Strategic Communications at the Duke University School of Medicine.