Reaching New Heights in Cancer Care

The only way to ascend a mountain is by putting one foot ahead of the other, one step and then another, over and again.

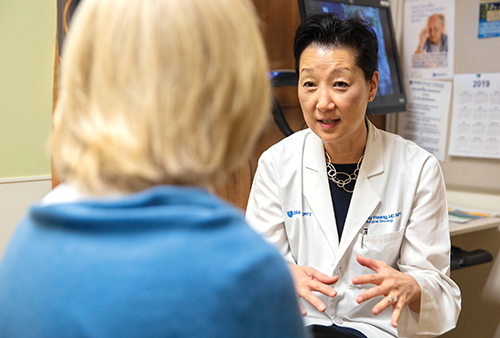

That tenacity took Shelley Hwang, MD, to the top of Mount Kilimanjaro in 2021, the highest mountain in Africa. It’s also led her to the pinnacle of a research quest that began decades ago as a daunting challenge.

Early in her career as a breast surgical oncology fellow, Hwang questioned the standard practice of treating patients diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) — a small cluster of abnormal cells in breast ducts — with mastectomies or lumpectomies, often followed by radiation. Many women even opted to remove both breasts from fear of breast cancer.

“I just wondered if we really needed to do all that,” said Hwang, the Mary and Deryl Hart Distinguished Professor of Surgery. “DCIS presents so differently from cancer, but we were treating it as if it were the same disease.”

This past December, after years of small trials and incremental steps, Hwang achieved a research milestone, presenting data at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium and simultaneously publishing in JAMA that a watchful waiting approach to DCIS is, at least initially, a viable alternative to surgery.

If longer-term data confirm the findings, Hwang will have reached one important summit of her career-long journey, possibly changing the standard of treatment for tens of thousands of women and men diagnosed with DCIS.

“Surgery has consequences that patients may live with long after treatment,” Hwang said. “If patients have chronic pain or numbness, or they don't even have a breast the rest of their lives, that is life-changing for that woman. We can’t ignore these effects that our patients experience that impact their quality of life.”

A Different Route

Hwang’s surgical breast oncology fellowship was at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, and it was there she began questioning the medical dogma around DCIS.

Since at least the 1990s, the drumbeat was on early detection and early treatment. It’s an approach many credit with contributing to the decline in U.S. death rates from breast cancer, even as the nation’s incidence of breast cancer has increased.

But Hwang saw some contradictions. Often, a diagnosis of DCIS and subsequent treatment depended on the pathologist’s report, or a reading of the radiology scans. Other abnormalities were flagged but watched closely, similarly to a benign condition called breast atypia.

“It just seemed there was a lot we didn’t know about this disease,” Hwang said.

As her career advanced and she joined the University of California at San Francisco, she met a fellow skeptic in Laura Esserman, MD, who became a close colleague and research collaborator.

As early as 1999, Hwang and Esserman were challenging the need for all DCIS patients to undergo surgery and advocating for a deeper understanding of the condition.

“Current treatment modalities may be overly aggressive because many cases of DCIS may not recur or progress to invasive cancer. Until we are better able to identify those patients at low risk for progression, it is unlikely that current treatment will change,” they wrote in the journal Surgical Clinics of North America.

Over the next decade, the two published dozens of research studies that established them as national leaders. In 2011, they shared results of a small study showing the feasibility of treating DCIS with regular scans instead of surgery.

Another, larger study followed with similar results, and by 2016, Hwang and Esserman had gained a level of fame uncommon to cancer researchers when they were heralded among TIME magazine’s “100 Most Influential People.” The singer and breast cancer survivor Melissa Etheridge wrote their tribute.

The following year, Hwang was named the principal investigator of the COMET study, a large, national clinical trial testing two different management strategies for low-risk DCIS: watchful waiting vs. surgery. COMET — which stands for Comparing an Operation to Monitoring, with or without Endocrine Therapy — was funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

On Dec.12, 2024, Hwang unveiled the first planned analysis from the COMET study, validating that watchful waiting is safe and effective, at least as an initial approach.

Next Steps

In the fall of 2021, Bonny Moellenbrock had a suspicious mammogram and underwent a biopsy that found DCIS. Her doctor immediately referred her to a surgeon, who recommended the cells be removed, followed by radiation.

“I thought that was excessive,” Moellenbrock said, especially because people can only be exposed to so much radiation before it’s no longer a therapeutic option. “If you do get invasive breast cancer, you would want to be able to use radiation.”

So she headed to Duke for a second opinion, where she learned of the COMET study. To her relief, she was randomly assigned to the active waiting group and has been carefully monitored every six months for two years. She also takes hormone therapy.

Things are going well. While additional spots have been identified through the monitoring, she remains confident that she will have every weapon at the ready if needed.

“Hopefully other women will not have to have the extensive treatment that they had in the past for DCIS,” Moellenbrock said. “I have two daughters, so I'm excited that they will have other options for treatment should they be diagnosed with DCIS — that they would not have to go through surgery or radiation, with side effects and the cost of that and still be safe and healthy.”

Hwang said these first findings from the COMET study are encouraging, but she is clear that longer-term data are needed for definitive success. Still, she is savoring the view from this vantage and excited to imagine what these results could mean for future patients with DCIS.

For Hwang, another major goal toward properly treating DCIS is gaining the ability to identify which clusters of cells are, indeed, cancerous. To that end, she has been leading another research effort to map a molecular atlas for DCIS as part of the NCI’s Cancer Moonshot Program, the Human Tumor Atlas Project.

In 2022, the team reported a major advance toward distinguishing whether the early pre-cancers would develop into invasive cancers or remain stable. More work is underway to make the gene classifier a clinical test that can be used in real-life settings, based on samples collected from patients who participated in the COMET Study. The patient-powered aspect of this research has been central to the clinical trial, which was a powerful partnership between researchers and patient advocates at almost 100 trial sites.

Onward and Upward

Hwang’s determination to find the answers that will lead to better cancer care mirrors another of her passions: climbing mountains.

“It was an amazing experience,” she said of summitting Kilimanjaro. “There's an important parallel between doing research and climbing mountains. Both are about setting a BHAG — a big, hairy, audacious goal, something that is ambitious but achievable. And it’s the focus on that North Star that is going to keep you inspired through all the inevitable setbacks.”

And so she keeps going, one step at a time, over and again, toward a goal that could help change the lives of thousands.

Sarah Avery is director of the Duke Health News Office

Photos by Shawn Rocco, Video by Matt Talhelm and Shawn Rocco

Kilimanjaro photo provided by Shelley Hwang