Precisely Right: Data Drives A Dream for the Cancer Field

Charles Riggan, 68, (pictured above with clinical trial nurse coordinator Quinna Lawson) is well-known on the clinic floor for the Werther’s Original caramels he passes out during almost-weekly visits to Duke Cancer Center.

Though he doesn’t eat them — he’s diabetic — Charles said the hard candies help “smooth things over” and put a smile on the faces of people that take care of him.

“I like to make people happy,” said Charles, a self-described “jack of all trades and master of none” who was in the customer-facing trucking, restaurant, and carpentry business for 40 years. “If a small piece of candy makes someone happy, then it’s worth it.”

Charles has stage 4 rectal cancer. It was discovered after a routine colonoscopy a year ago September — ten years after a clean scan. After undergoing two rounds of chemotherapy, surgery, then a “cleanup” round of chemo, his body rejected the therapy and the cancer spread to his liver. His cancer cells had developed a resistance to the drug and mutated, an all too common occurrence in cancer.

Jingfan (Jean) Huang, a native of China, came to the U.S. for graduate school. She stayed in the U.S. to work as a chemist, met and married her husband, a biologist, and settled down. Last year, after taking several years off from working outside the home to raise their three kids, the Chapel Hill, North Carolina-resident joined her husband’s biotech start-up.

In February, Jean traveled to China to celebrate Chinese New Year with family. She’d been looking forward to eating some delicious holiday dishes, but, to her surprise, wasn’t in the mood. Tired, cold, weak, and dizzy as well, she suspected jet lag and shrugged it off. But severe stomach pains two days before she was to return to Chapel Hill would land her in a local hospital. There she was diagnosed with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, a rare form of a rare cancer that originates in the bile ducts in the liver. Jean, 55, was in shock.

After beginning chemotherapy treatment in March for stage 4 cancer that had already spread to her liver and lymph nodes, she started to feel better, and even vacationed in Athens and Rome. By early June, after eight cycles of a more potent chemotherapy combination, the cancer in her liver and lymph nodes had grown.

Data Driven

When standard-of-care (first-line) treatments fail to keep a patient’s cancer under control, oncologists often consider targeted therapies — drugs which block the growth and spread of cancer by interfering with the specific molecular alterations (tumor-cell specific genetic changes) that drive that cancer.

However, in this, a more personalized approach, commonly referred to as targeted therapy or personalized medicine, comprehensive genomic profiling tests (also called next-generation sequencing) must be run on a patient’s tumor cells in order to determine if there’s a drug in existence that targets the particular molecular alteration that may be fueling their cancer — whether that’s an FDA-approved therapy, a drug being tested in a clinical trial, or a drug (not FDA-approved for their cancer) that the patient may be able to get in extenuating circumstances.

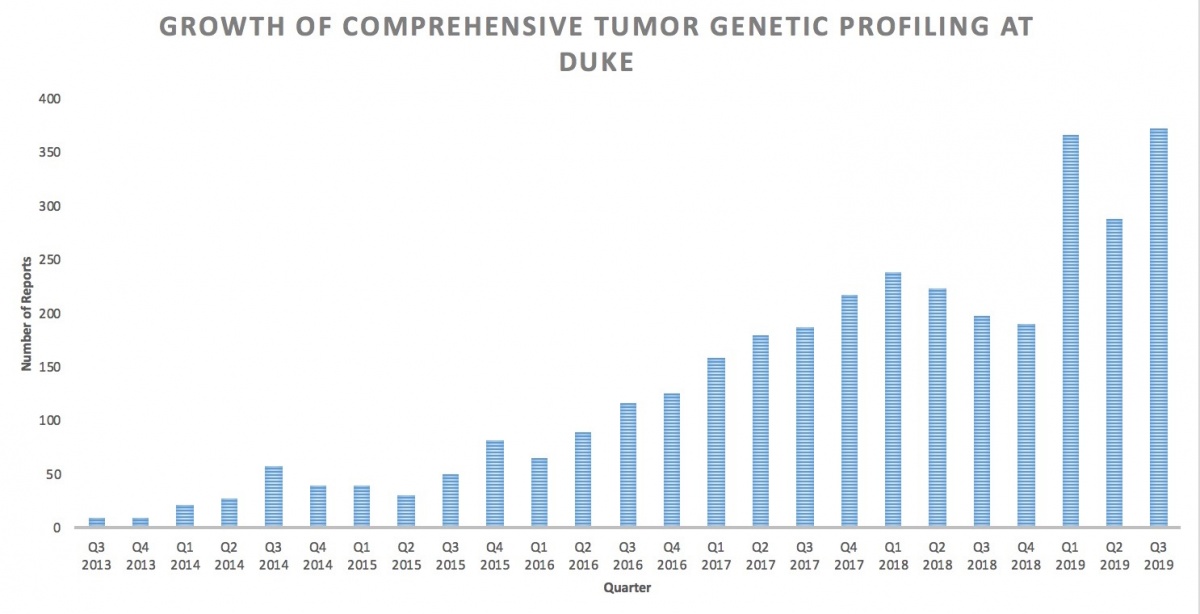

The Duke Cancer Institute (DCI) has partnered with leading private diagnostics companies since 2014 on these comprehensive genomic profiling tests.

One of these tests screens the tissue of patients with various advanced solid tumor cancers (not blood cancers) for as many as 400 molecular alterations. The other, more experimental test (mainly done in lung cancer), called a “liquid biopsy,” screens the circulating tumor DNA found in a patient’s blood for up to 73 molecular alterations. (A test that screens for 50 different molecular alterations common in blood cancers is done in-house at DCI.)

In 2017, the DCI partnered with Duke’s Department of Pathology and Duke University Health System Clinical Laboratories on an ambitious Precision Cancer Medicine Initiative to create a secure and searchable electronic registry to organize all the accumulated molecular testing data (the Molecular Registry of Tumors ), establish a multi-disciplinary Molecular Tumor Board to evaluate that data, and get the data in shape to join a U.S.-based international molecular tumor registry.

The homegrown MRT now contains comprehensive genomic profiling data from more than 3,900 patients, across more than 40 cancers. It’s grown exponentially. Its architects — Michael Datto, MD, PhD, director of the DUHS Clinical Molecular Diagnostics Laboratory, and DUHS clinical informatics architect Christopher Hubbard — say it’s truly become a “robust entity.”

Molecular Tumor Board meetings, led by John Strickler, MD, and Matthew McKinney, MD, both of them Duke medical oncologists on faculty at the School of Medicine, have come to be standing-room-only. Pathologists, oncologists, scientists, medical geneticists, and clinical trial teams put their heads together over lunch every Monday to discuss the 10 most challenging cases of patients who could benefit from a targeted therapy. Genetics scientist Michelle Green, PhD, hired this spring as program leader for the Molecular Tumor Board, helps the team track new targeted therapies entering the market, new indications for older targeted therapies, and promising research, and utilizes MrT to match patients to drugs that could work for them. The team also uses the test results to predict, in some cases, which drugs may not work (potential resistance to treatment) for a patient or whether that patient may have inherited their cancer.

Found a Match

This spring, while Charles and Jean were still in the initial stages of their cancer treatment, their cases came before that Molecular Tumor Board. Comprehensive genomic sequencing tests had been run on both in advance so that their oncologist Gerard Blobe, MD, PhD, would be ready with a possible back-up plan should their bodies reject current treatments.

Clinical trial nurse coordinator Quinna Lawson, BSN, RN, whose main focus is early stage clinical trials across all cancer types, was listening. The phase 1 trial team had made regular attendance a priority this year after discovering a few patients a week, through the tumor board, that could potentially go on a study.

Lawson knew about a massive multi-institutional National Cancer Institute-led study (the Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice (MATCH) trial) for which Jean and Charles might qualify. She did the legwork needed to preliminarily confirm their eligibility.

This summer, first Jean, and then Charles, were able to get onto separate MATCH trial subprotocols quickly when it was time for that backup plan.

Uniquely, MATCH (which is still recruiting), through several subprotocols, is seeking to determine the effectiveness of using drugs, which may be approved to target specific molecular alterations in one type of cancer, to treat other types of cancers with that same molecular alteration.

As a result, Jean, who has a rare form of bile-duct cancer, was able to take a drug (erdafitinib) only FDA-approved so far to treat a particular type of bladder cancer, but that targets the same molecular alteration she has. And Charles, who has rectal cancer, began infusions of the drug (copanlisib), which is only FDA-approved so far to treat follicular lymphoma but that targets the same molecular alteration he has.

“Historically, we’ve been used to treating cancers based on their tissue of origin. Treating a lung cancer like a lung cancer or a colon cancer like a colon cancer,” explained Blobe, a DCI faculty member who runs a basic and translational cancer research lab. “It was really immunotherapy that opened the door to considering that if patients have a particular alteration it doesn’t matter what cancer they have, they might respond. We’ve seen proof-of-principal that a molecular alteration can actually guide therapy perhaps better than the tissue of origin. And that’s what really opened the door to us thinking about that across targeted therapies. Treating patients based on what their molecular testing shows has been a long-standing dream for the field that’s finally being realized, so this trial is very exciting.”

Their Best Shot

The initiative has changed the game for Duke cancer patients, physicians and researchers. Duke investigators, including Blobe, are already using MrT to answer research questions and develop pre-clinical studies and clinical trials.

Blobe said not only is the “hit rate” of matching patients to targeted therapies much higher than it used to be, but the number of patients responding to these therapies is higher and the number of patients having a dramatic response is higher.

Before the MrT registry was created and a Molecular Tumor Board mobilized, the chances a treatment decision would be made based on genomic profiling data, Blobe noted, were much lower.

Five months into the trial, Jean’s cancer is shrinking. With the trial drug she’s been eating and sleeping well and even had the stamina for a business trip to China — with a fun stop-over in Thailand.

“The clock is ticking,” acknowledged Jean, who plans to work alongside her husband and indulge her love of travel as long as she can.

She’ll stay on the trial as long as treatment is either controlling or decreasing her disease, and as long as she can tolerate and manage the sometimes-painful side effects.

For a few months, Charles wondered aloud to Lawson how he “got so lucky” getting on the clinical trial. His cancer had not progressed and the only major side-effect — a rise in blood sugar — was managed by adjusting his usual insulin dosage.

Unfortunately, just before Thanksgiving, Charles learned his cancer had grown and he had to stop the trial. Fortunately, Blobe was able to find him another option. He began conventional second line chemotherapy and targeted therapy December 10 and his next infusion will be Christmas Eve day.

“I’ve got a bulldozer, a tractor, a track hoe, two airplanes, a tractor trailer, and an old lady,” joked Charles, who lives on “a little bit of land” about 25 miles from Duke and recently got involved with his son’s gunsmithing business. “I ain’t quite ready to give up yet.”

“I have some patients for whom treatment has been their golden ticket,” said Lawson. “But it’s hard to see when it doesn’t work … The best part of my job is getting to know the patients and feel like I’m in some way helping them get to their next step, whatever that may be.”

Julie Harbin is a writer with the Duke Cancer Institute.