Harvey Cohen Says Yes

Harvey Jay Cohen, MD, never planned to go into geriatrics. It wasn’t a word he heard in medical school in the 1960s. In fact, he hadn’t planned to go to medical school either. Once there, he certainly wasn’t planning to become a clinician--he just wanted to do research. Even after deciding to become a clinician-scientist, he chose hematology-oncology as his specialty. He never gave geriatrics a thought.

But life has a way of presenting opportunities, and Dr. Cohen has a way of saying yes.

“You’ve got to stay open to interesting opportunities,” he says. “If you think you would enjoy it, and you have a skill set that seems to match it, give it a shot.”

Today, at age 78, Cohen, the Walter Kempner Professor of Medicine in the Department of Medicine, is considered a leading pioneer in the field of geriatrics.

“He’s one of the fathers of geriatrics nationally, not just at Duke,” says Cathleen Colón-Emeric, MD, professor of medicine and chief of the Division of Geriatrics, who trained at Duke and counts Cohen as an important mentor.

Mary Klotman, MD, dean of the Duke University School of Medicine agrees. “He’s an iconic figure in geriatric health,” she says. “Harvey has positioned Duke as a national leader in this field.”

And down the road at the University of North Carolina, Hyman Muss, MD, says, “Harvey continues to be a relentless leader in this field.” Muss, who holds the Mary Jones Hudson Distinguished Professorship in Geriatric Oncology, has known Cohen for decades, as a research collaborator, a co-chair of a national committee on geriatric oncology, and as a friend.

Courtesy of Duke Medical Library Archives.

Cohen arrived at Duke in 1965 for his internal medicine residency. Since then, he has held numerous leadership positions, including chair of the Department of Medicine (twice, once as interim), director of the Duke Center for Aging (for almost 40 years), chief of the Division of Geriatrics (which he founded), and director of the Durham VA Medical Center’s Geriatrics Research, Education and Clinical Center (which he helped get funded).

Beyond Duke, he has served as president of the American Geriatrics Society, the Gerontological Society of America, and the International Society of Geriatric Oncology.

For the past several years, he has been gradually stepping down from his many administrative roles. He admits he’s a bit tired of “the administrative stuff” and besides, he wants to open up leadership opportunities for the younger people he’s mentored.

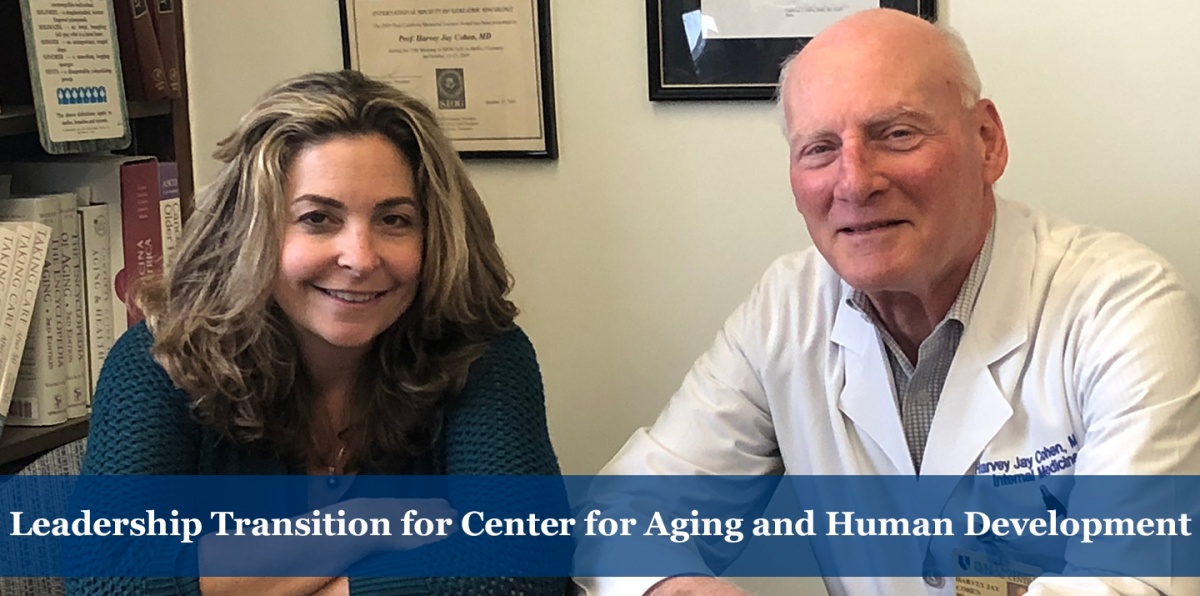

On June 30, 2019, he shed the last of his administrative roles when he turned over the reins of the Duke Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development to Heather Whitson, MD, MHS, associate professor of medicine (Geriatrics) and ophthalmology.

But don’t think Cohen’s retiring. He’s still all-in on research, education, and mentorship.

And refereeing the annual Turkey Bowl between VA and Duke internal medicine residents.

And playing in the annual house staff vs. faculty basketball game at Cameron.

Although he’s been a basketball player all his life, in recent games he’s spent more time on the bench than on the court: “There’s one place I feel my age,” he says. “I can’t run as fast or jump as high.” Still, he’s kept the same trim physique he’s always had. He stays in shape by walking where he needs to go on campus.

And he goes a lot of places on campus.

“He is everywhere,” says Diana McNeill, MD, professor of medicine (Endocrinology, Metabolism, and Nutrition). “You go to any departmental event, any medical center event, he’s there. His energy is contagious. When he talks, people stop and listen not only as a sign of respect but because he’s really wicked smart.”

In his free time, he also attends lots of Duke games: basketball, lacrosse, soccer, field hockey. “As long as there’s a ball, he’s there,” says Sandy, his wife of 55 years.

Harvey and Sandy met at Brooklyn College, where he majored in biology. As the first in his family to attend college, he wasn’t considering medical school until a college advisor suggested it as a way of earning a good living while doing research. “My dad always wanted me to make a living,” Cohen says, “so I went to medical school.”

He graduated from Downstate Medical College, also in Brooklyn, in 1965. He and Sandy picked Duke for his residency because Cohen hit it off with Eugene Stead, MD, who was chair of the Department of Medicine. . . and because they visited during an unseasonably warm Thanksgiving weekend and were entranced by visions of undergrads playing Frisbee in Duke Gardens.

After his residency, and a two-year research stint at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Cohen completed a hematology-oncology fellowship at Duke and joined the faculty with a specialty in multiple myeloma.

Soon, his unplanned journey toward geriatrics began.

In 1975, James Wyngaarden, MD, PhD, the chair of the Department of Medicine, asked Cohen to be the chief of medicine at the VA. “After a few refusals, I decided it was in my best interest to do that,” Cohen says. “I turned out to love it, and it got me into a more general medicine mode.”

Next, Daniel Gianturco, MD, a geriatric psychiatrist at the Duke Center for Aging, asked Cohen for help in applying for a VA grant to start a geriatrics fellowship program. The Center for Aging, established in 1955, had failed in an earlier bid to win one of these grants because the center focused primarily on psychiatric aspects of aging. “He came to me for two reasons--I was at the VA and I was an internist,” Cohen says. “Literally, those were my only two qualifications because I knew nothing, and I mean nothing, about geriatrics.”

After getting the grant, Cohen created the geriatrics fellowship program, and set up a Geriatric Evaluation and Treatment (GET) clinic at the VA so the fellows would have someplace to work.

By now, his interest in geriatrics was growing. “I realized most of the patients I dealt with in myeloma were older and I had always liked dealing with them,” he says, “so it started to make sense to me that geriatrics might be an area I could do something with.”

In the early 1980s, Cohen headed up the effort to get a grant to establish a Geriatrics Research, Education and Clinical Center (GRECC) at the Durham VA, and subsequently became the director.

About the same time, William Anlyan, MD, who was dean of the School of Medicine and chancellor for medical affairs, asked Cohen to become the director of the Duke Center for Aging.

Soon after, the Division of Geriatrics was born when it became obvious that the faculty working in the GET, the GRECC, and the Duke Center for Aging needed an administrative home. Again, Cohen was the natural choice to be the leader of the new division.

Looking back, Cohen says, “I’ve been very fortunate to have some good choices that in retrospect did fit my skill set,” he says, “and they turned out to be quite successful.”

He credits two of the programs that helped shape his career with shaping the field of geriatrics on a larger scale: the geriatric fellowship program and the GRECCs (there are now 20 GRECCs nationwide). “The VA recognized that its cohort of vets was aging at a faster clip than the general population,” Cohen says, “and in a very far-sighted way thought we ought to do something about that.”

Although Cohen calls geriatrics an “accidental career,” once he found himself on that path, he decided to devote himself to it fully.

He became active in national organizations to help shape the growing field of geriatrics and to promote Duke’s program.

He also incorporated geriatrics into his research, focusing on cancer care in the elderly. He had worked in an immunology lab at the NIH, so he set out to determine how changes in aging immune systems might affect outcomes for older patients with cancer.

This led to a productive vein of work looking for immune-system biomarkers that could be tied to functional changes, such as difficulty with walking, household chores, dressing, and bathing. He and his team showed that increased blood levels of a signaling protein called IL6, which is associated with inflammation, were predictive of functional disability in older people.

Later, he worked on geriatric assessment, which involves assessing hearing, vision, memory, mood, strength, gait, and social support in older patients to inform treatment decisions. It’s now become an established part of clinical care in the U.S. and other parts of the world. He’s also been instrumental in applying it to geriatric oncology patients.

“Oftentimes when you do these geriatric assessments, information comes out that hadn’t been known,” he says. “If this cancer patient has functional decline, then you might know they need physical therapy to help bolster their potential responsiveness to [cancer] treatment.”

He’s continuing to pursue both of these avenues by looking for biomarkers that can be used in combination with geriatric assessment to provide an even more comprehensive and personalized guide to treating cancer in older patients.

In addition to his research, Cohen enjoys teaching and mentoring students, house staff, and young faculty members. “Watching them succeed--that’s fantastic; that’s the fun of it all,” he says.

His mentees attest that he listens well, asks great questions, and isn’t overly directive. “One of Harvey’s biggest contributions is the next generation of leaders he has trained,” Klotman says, rattling off the names of faculty members in the Division of Geriatrics. “These are extraordinary leaders who all carry a piece of Harvey in what they do.”

He says being around students and trainees keeps him young: “It’s a constant renewal to be able to deal with young people. It keeps you thinking and allows you to learn stuff all the time. If I retired, that’s what I would miss more than anything.”

While he’s not planning on retiring soon, Cohen knows the day will come. When it does, he’s looking forward to spending more time with his family. He and Sandy have two children and four grandchildren, who live in Seattle and Connecticut.

But he doesn’t have any hobbies like gardening or woodworking or golf that he’d like to spend more time on.

“The stuff I like doing is what I do,” he says.

Mary-Russell Roberson is a freelance writer in Durham. She covers the geriatrics and aging beat for the Department of Medicine in the Duke University School of Medicine.