Sensory neurons in the head and face tap directly into the brain’s emotional pathways

Hate headaches? The distress you feel is not all in your -- well, head. People consistently rate pain of the head, face, eyeballs, ears and teeth as more disruptive, and more emotionally draining, than pain elsewhere in the body.

Duke University scientists have discovered how the brain's wiring makes us suffer more from head and face pain. The answer may lie not just in what is reported to us by the five senses, but in how that sensation makes us feel emotionally.

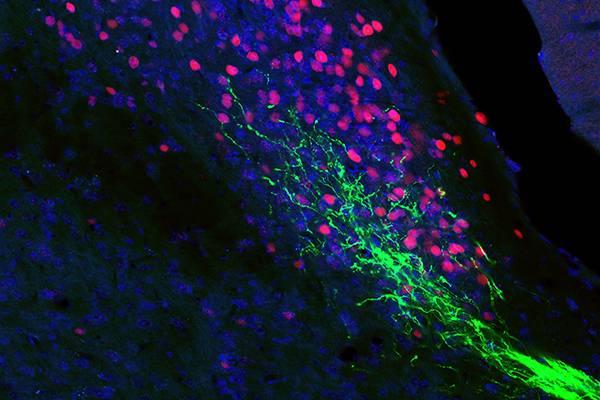

The team found that sensory neurons that serve the head and face are wired directly into one of the brain’s principal emotional signaling hubs. Sensory neurons elsewhere in the body are also connected to this hub, but only indirectly.

The results may pave the way toward more effective treatments for pain mediated by the craniofacial nerve, such as chronic headaches and neuropathic face pain.

“Usually doctors focus on treating the sensation of pain, but this shows the we really need to treat the emotional aspects of pain as well,” said Fan Wang, a professor of neurobiology and cell biology at Duke, and senior author of the study. The results appear online Nov. 13 in Nature Neuroscience.

Pain signals from the head versus those from the body are carried to the brain through two different groups of sensory neurons, and it is possible that neurons from the head are simply more sensitive to pain than neurons from the body.

But differences in sensitivity would not explain the greater fear and emotional suffering that patients experience in response to head-face pain than body pain, Wang said.

Personal accounts of greater fear and suffering are backed up by functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), which shows greater activity in the amygdala -- a region of the brain involved in emotional experiences -- in response to head pain than in response to body pain.

“There has been this observation in human studies that pain in the head and face seems to activate the emotional system more extensively,” Wang said. “But the underlying mechanisms remained unclear.”