Two Duke doctors discuss reasons, possible solutions in media briefing

COVID-19 has shone a stark light on America’s economic and racial health disparities, proving there is no one-size-fits-all strategy to test and treat people for the disease, two Duke experts emphasized Thursday.

The pandemic has illuminated the struggles minority populations have in obtaining good information, getting tested and finding help when infected. But there are ways to improve the situation, the two health experts said.

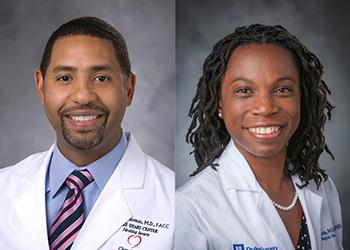

Drs. Kevin Thomas and Oluwadamilola Fayanju spoke to and took questions from media members Thursday. Here are excerpts:

ON COVID-19 HIGHLIGHTING HEALTH DISPARITIES

Dr. Kevin Thomas, cardiovascular disease specialist

“COVID has done a lot of things for us. One of those is (it) really highlighted issues around health disparities not just as it related to COVID but what we deal with on a regular basis.”

“We need to continue to work hard to really understand the nature of how significant this impact is on vulnerable populations. Most of those populations are going to be folks who have been historically underrepresented.”

“While we’re still getting a lot of information from many outlets … of the millions of cases that exist currently, we still don’t have information on race and ethnicity for up to half those cases. We see how bad the numbers are, but those are likely underestimates.”

“Understanding that data better and continuing to report transparently that data is incredibly important.”

“There are also issues around awareness. As you go out into different communities, I think we can do a better job of explaining to people the realities of what we’re dealing with, with COVID and opportunities to practice safe customs that will potentially reduce the spread of the disease.”

“We know testing is a problem. If you look at some of our data here in Durham, and when you overlay where some of the testing sites are located with the populations who are most at risk – the Latino and African-American communities – there’s not many testing opportunities for those folks.”

ON BARRIERS TO CARE FACING PEOPLE OF COLOR

Dr. Oluwadamilola Fayanju, surgeon, breast cancer specialist

“Patients may not have an opportunity to have a primary care provider that’s keeping tabs on their health.”

“People may also have issues with insurance. If you’re in a state that has not expanded Medicaid – which includes North Carolina – that means there are a number of individuals for whom the health care exchange through the Affordable Care Act is unattainable.”

ON COVID TESTING IN VULNERABLE COMMUNITIES

Dr. Kevin Thomas

“There have been challenges ubiquitous across the country in terms of testing and access. Understanding where these sites are being placed, being thoughtful about that, and understanding the limitations for certain populations. Drive-up testing has become a very popular way to test individuals. That really doesn’t consider who has transportation and who doesn’t. For those who potentially can access testing sites but are reliant on public transportation, that really promotes some challenges as well.”

“I think there are really legitimate concerns to think about. We can be more thoughtful about these things. Other opportunities we could consider is mobile testing – could we get out into these communities and begin to test people?”

ON HOW TO REMOVE BARRIERS TO TESTING

Dr. Oluwadamilola Fayanju

“Access to testing is both geographic as well as logistical. Even if testing is in certain places, the question is, is testing available at the times of day when people can access testing? If you’re someone who works multiple shifts, if you work somewhere where you can’t take time off from work, can you physically get somewhere to get tested?”

“Another important barrier is whether you have a physician who can prescribe a test and also a physician to follow up on the results of that test.”

“Making sure having access to testing isn’t dependent on having a primary care provider, given that many people who are already in a medically underserved community will not have access to a (personal care provider).”

ON OTHER HEALTH HURDLES FACING MINORITY POPULATIONS

Dr. Kevin Thomas

“Some individuals, based on their economic and socio-economic situations, may ignore symptoms because they need to work. What you hear from time to time from patients is, ‘I can’t afford to be sick. My family is dependent on income.’ … By the time they do seek care, they’re very advanced in their stages.”

“There’s also this interest of trust. It’s important. It’s real. It’s generational. A lot of people are hesitant to seek care. Not having the utmost confidence that clinicians in health care systems, due to the years and years of structural racism and bias, they don’t feel comfortable coming to institutions to seek treatment.”

“There’s multiple layers to consider here. We need to be intentional and purposeful in terms of really studying and understanding these disparate rates we see. There’s a lot of work to be done.”

ON MINORITY HEALTHCARE WORKERS GETTING SICK

Dr. Kevin Thomas

“When people think about essential employees, often they don’t think about individuals who are really kind of behind the scenes. Many of these individuals are from underrepresented racial and ethnic background.”

“When we talk about essential employees, we need to be thoughtful about what that means. There’s a lot of individuals who really aren’t accounted for, who have to go to work. They’re vitally important.”

Dr. Oluwadamilola Fayanju

“Many of the places that have served as hot spots for infection are precisely the areas where people of color as well as immigrants are more likely to be working on the front lines.”

“Nursing home workers are disproportionately people of color, people who are immigrants. And some of those individuals may not have access to health care. Some of those individuals may be undocumented. There are multiple reasons why they are vulnerable.”

“One big difference between us and the United Kingdom … is that in the United Kingdom there is universal health care. Here, people can be bankrupted if they get sick.”

ON COVID MESSAGING TO MINORITY COMMUNITIES

Dr. Oluwadamilola Fayanju

“Mixed messages are inevitable when we’re dealing with a new pathogen. Early on we weren’t even sure about the most consistent form of transmission.”

“One concern is that there is still a lot of mistrust about any government-mandated program related to health care. There is going to be a lot of mistrust surrounding the vaccine when it’s available. That’s something the medical community should be preemptive about trying to address.”

“Messages that should be absolutely clear is that you should be wearing a mask. Hand-washing is important. Avoiding mass gatherings is important.”

“If we had a drug that we knew would reduce transmission of the disease by a factor of five, we would all be jumping to do that. It’s kind of amazing that we know that masks actually significantly decrease the likelihood of transmission, but yet there are people unwilling to wear it.”

“Wearing a mask is a form of kindness, a form of citizenship. You’re looking out for other people as well as yourself.”

Dr. Kevin Thomas

“The reality of the situation is, unfortunately for a lot of underrepresented racial and ethnic populations, social distancing is challenging. They live in homes that are multigenerational. There’s a lot of individuals in the homes. That makes things really challenging to (distance).”

“The masks should be – and I emphasize ‘should be’ – the low-hanging fruit. It has been proven. I struggle because I know there are some people who don’t have access to masks. That isn’t a trivial thing.”

“The messaging is certainly important, but the behavior, too – what we do to bring about change – is important, too.”

ON COVID IMPACT ON CHILDREN

Dr. Oluwadamilola Fayanju

“There is a psychological toll of COVID-19 as well. People around the world are trying to work, and parent, and teach, and care for others, all at the same time, in the same space. There’s going to be a lot of kids for whom their parents are home, but their parents are stressed. Their parents lost their jobs. Their parents are trying to work while watching them. So those children may be having an element of neglect, and that’s no small thing either.”

Dr. Kevin Thomas

“There’s just a lot of unknowns here. When we think about the pressures on multiple levels, what’s going to happen with schools, it’s really important to be thinking about that population, understanding the risk and being transparent.”

“There’s going to be some really difficult decisions to make that have rippling effects on parents, teachers, caregivers, etc.”

Faculty participants

Dr. Oluwadamilola “Lola” Fayanju

Lola Fayanju is an assistant professor of surgery and population health sciences in the Duke School of Medicine, director of the Durham VA Breast Clinic and associate director for disparities and value in health care with Duke Forge, the university’s center for data science. Her research includes variants of breast cancer that are often more common among racial and ethnic minorities.

lola.fayanju@duke.edu

Dr. Kevin Thomas

Kevin Thomas is an associate professor in the Division of Cardiovascular Disease at the Duke School of Medicine, where he is also assistant dean for underrepresented faculty development and co-director of the Duke Health Disparities Research Curriculum. Thomas is also director of health disparities research and faculty diversity at the Duke Clinical Research Institute.

kevin.thomas@duke.edu

--

CONTACT:

Steve Hartsoe

steve.hartsoe@duke.edu

Duke experts on a variety of other topics related the coronavirus pandemic can be found here.

This article first appeared in Duke Today