A trio of researchers at Duke University School of Medicine who have long collaborated to study how the immune system’s antibodies respond to HIV infection are now focusing on the new coronavirus.

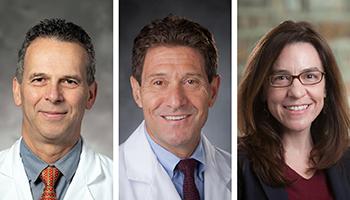

Guido Ferrari, MD, associate professor of surgery; David Montefiori, PhD, professor of surgery; and Georgia Tomaras, PhD, professor of surgery, have deep expertise and experience in designing assays, which are laboratory procedures that measure the presence of different kinds of certain substances. In their labs, they measure the presence of antibodies in blood.

“We’ve been [using our assays for] evaluating HIV vaccines, and now we’re applying that to understand protective immunity for SARS-CoV-2, to identify antibody responses that correspond to protection against the virus,” Tomaras says.

Their assays, which can be used during or after natural infection or vaccination, are designed not only to indicate the presence or absence of antibodies, but to reveal the types and amounts of antibodies and the timing of their production.

Understanding these kinds of nuances in the immune response to a particular pathogen is crucial to vaccine development. Simply having antibodies against a virus doesn’t necessarily protect a person against future infection. For example, HIV vaccine trials and studies of other respiratory diseases such as SARS and MERS have shown that some antibody responses protect against future infection, while others don’t and can even be harmful.

The researchers are first studying immune response in patients with COVID to understand the progression of the response over the course of the infection and to identify types of response that seem to be most effective in vanquishing the disease. They will use this information to help predict whether an immune response provoked by a vaccine is likely to protect the vaccinated person from infection. The three researchers will be actively involved in evaluating serum from vaccinated patients at Duke and beyond to help identify the most effective vaccines among the many current candidates.

A better understanding of antibody response could also help guide treatment decisions. For example, a certain antibody response in a patient could indicate a more severe form of the disease is likely.

Each of the three researchers specializes in a different part of the antibody and its function.

“We look at different aspects of the immune response in a way that complements one another,” Montefiori says. “Together, our combined labs can generate a rather comprehensive set of data on the spectrum of immune responses that are seen in patients so that we can really understand the immune response in a lot of detail.”

That detailed understanding is key to being able to evaluate a vaccine-stimulated immune response and predict how well it will protect a person against infection.

“Maybe not everyone will be able to develop the protective response [from a vaccine] and we need to know why,” says Ferrari. “What is the type of response we need? What is the level of the response we need? How many times do we need to immunize to reach that level? How long will immunity last?”

“We want to help people design the right types of vaccines and identify the ones that are the most promising,” Montefiori says.