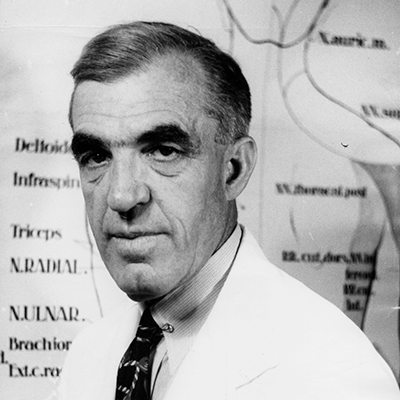

When Wilburt C. Davison, MD, the founding dean of Duke University School of Medicine, was looking for a candidate to serve as the school’s inaugural chair of the Department of Medicine, the first name that came to mind was that of Frederic M. Hanes, MD.

Hanes, the school’s professor of neurology—at the time, there was only one—was a member of the founding faculty. He was a brilliant physician and scientist, a man of deep principles and unquestioned character, and a natural leader. Davison was prepared to name him chair, but he was dissuaded by friends of Hanes who insisted he would have no interest in the administrative duties required of the position. Davison named Harold L. Amoss, MD, instead.

Those friends, it turned out, were wrong. “I was never so greatly misinformed,” Davison wrote in his autobiography, Davison of Duke: His Reminiscences.

When Amos resigned in 1933, Davison got another chance. This time he did offer Hanes the job, and Hanes accepted the chairmanship, administrative duties and all. He led the department with great skill and dedication, overseeing its growth and progress until his tenure was cut short by his untimely death in 1946.

Hanes was among the most influential and warmly remembered members of the early School of Medicine faculty. Born in Salem, North Carolina, in 1883, he earned his undergraduate degree at the University of North Carolina, received a master’s degree from Harvard, and was awarded his MD from Johns Hopkins in 1908.

He served at Columbia University, Washington University, the Rockefeller Institute, Queens Square Hospital in London, and at the Medical College of Virginia until the United States entered World War I in 1917, when he resigned his practice to offer his services to the military. Hanes became a lieutenant colonel in command of Base Hospital 65 near Brest, France, treating wounded American soldiers before they were placed on transport ships for the voyage home.

After the war, Hanes returned to private practice in Winston-Salem until Davison invited him to join the faculty when the School of Medicine opened in 1930. As Florence McAllister Professor of Medicine and chair of the department, he taught and conducted research in neurology and pathology and mentored a generation of students and fellow faculty.

Hanes’s influence extended far beyond the hospital and School of Medicine, and in fact is visible to this day. In the early 1930s, when he made his walk to his office in what is now known as the Davison Building, every day he passed by a ravine near the hospital. The site had once been intended to be filled with water to create a campus lake, but that project had never been completed, and over time the depression had become an unsightly dumping ground filled with debris.

Hanes envisioned something better. A passionate horticulturist, he persuaded Sarah Pearson Angier Duke, the widow of Benjamin Duke, one of the university’s founders, to donate $20,000 to transform the site into a garden blooming with tens of thousands of irises, daffodils, and other flowers.

Heavy rain destroyed the original gardens, but Hanes refused to give up. After Sarah Duke died in 1936, he worked with her daughter, Sarah Duke Biddle, to rebuild the gardens bigger and better than ever. “It is my belief that your mother and yourself have created something uniquely beautiful here at Duke, and that it is destined to become one of the famous gardens in the country,” he wrote to Biddle. “It will surely be visited by many thousands each year.”

Sarah P. Duke Gardens dedication ceremony, April 21,1939.

Sarah P. Duke Gardens dedication ceremony, April 21,1939.He was right; Sarah P. Duke Gardens is now one of the university’s star attractions, attracting almost half a million visitors annually.

Hanes and his wife, Elizabeth, gave generously to Duke during their lives and beyond. They donated everything from funds to build the Elizabeth P. Hanes House dormitory for nurses to a collection of medical books that helped build Duke’s medical library into one of the finest of its kind in the South.

When Hanes died on March 25, 1946, he left his estate to the School of Medicine, with half dedicated to the Department of Medicine and half for other needs. His will also established the Frederic M. Hanes Fellowships, which supports six to 12 months of full-time research for medical students. “It is my hope that this bequest will contribute to the training of intelligent physicians, and that quality and not quantity will be the constant aim of the School,” he said in his will.

His loss was keenly felt at Duke and, indeed, throughout North Carolina and the world of medicine. The North Carolina Medical Journal dedicated its March 1947 issue to him.

“He was distinguished in the art of medicine, but he excelled also in a much more difficult art, the art of living,” said Harvie Branscomb, PhD, dean of the Duke Divinity School and longtime chancellor of Vanderbilt University, at his memorial service. “He loved much, and he gave of himself and his means to the things which he loved. Thus his many-sided personality has impressed itself upon our institutions, even upon our landscape, but most of all upon our hearts.”

Sarah P. Duke Gardens

Sarah P. Duke Gardens