Mutation prompts lung tumor cells to morph into gut cells.

Tumors are notoriously mixed up; cells from one part often express different genes and adopt different sizes and shapes than cells from another part of that same tumor.

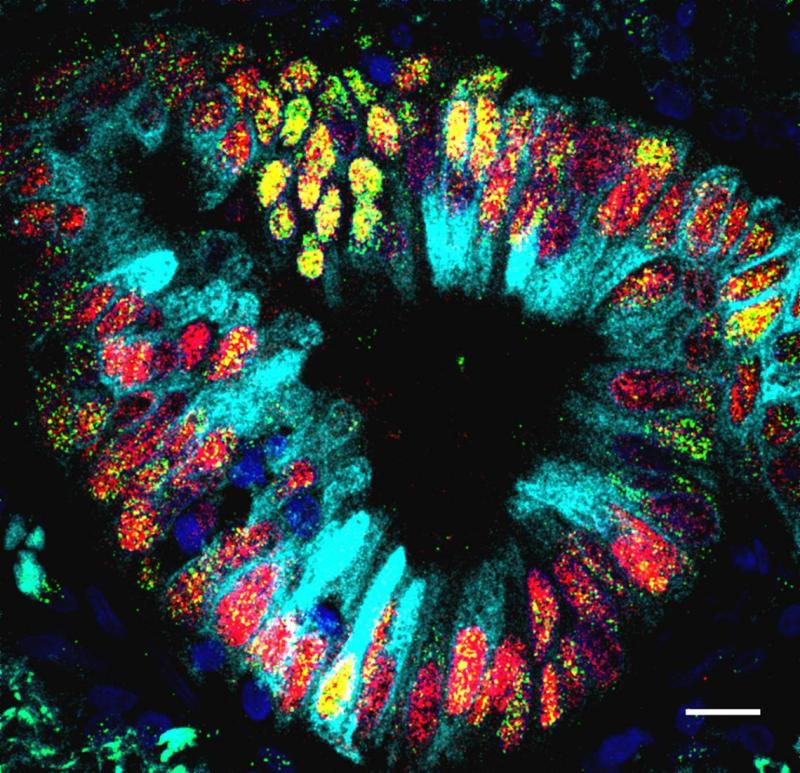

Still, a team of researchers were surprised when they recently spotted a miniature stomach, duodenum, and small intestine hidden among the cells of lung tumor samples.

They discovered that these cells had lost a gene called NKX2-1 that acts as a master switch, flipping a network of genes to set the course for a lung cell. Without it, the cells follow the path of their nearest developmental neighbor -- the gut -- much like a train jumping tracks when a railroad switch fails.

The findings, published March 26 in the journal Developmental Cell, underscore the amazing resilience and plasticity of cancer cells. Such plasticity can presumably enable tumors to develop drug resistance, arguably the biggest challenge to successful cancer treatment.

“Cancer cells will do whatever it takes to survive,” said Purushothama Rao Tata, Ph.D., lead study author and assistant professor of cell biology at Duke University School of Medicine and a member of the Duke Cancer Institute. “Upon treatment with chemotherapy, lung cells shut down some of the key cell regulators and pick up the characteristics of other cells in order to gain resistance.”

Tata has spent most of his career studying the cell types that make up normal lung tissue and how these cells display flexibility during regeneration following an injury. Tata began to wonder whether some of the same rules that he had found governing the normal development and regeneration of tissues might also be responsible for the jumbled nature of tumor cells.

He decided to focus on non-small cell lung cancer, which accounts for 80 to 85 percent of all lung cancer cases. Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide, and has one of the lowest survival rates among all cancers. Tata analyzed data from the Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, a large consortium that has profiled the genomes of thousands of samples from 33 different types of cancer. He found that a large proportion of non-small cell lung cancer tumors lacked NKX2-1, a gene known to specify the lung lineage. Instead, many of them expressed a number of genes associated with esophagus and gastrointestinal organs.

[Video:https://youtu.be/WT9Ff3ewU54]