It doesn't look or act like most breast cancers. But inflammatory breast cancer may just hold the secret to understanding what happens when any breast cancer turns deadly.

When you think of breast cancer, you probably picture a telltale lump. Gayathri Devi, PhD, dispels that image with a few photos: a person’s chest with what looks like a rash, then a thermographic version of the image showing the heat from elevated blood flow spread throughout the chest. This is inflammatory breast cancer (IBC).

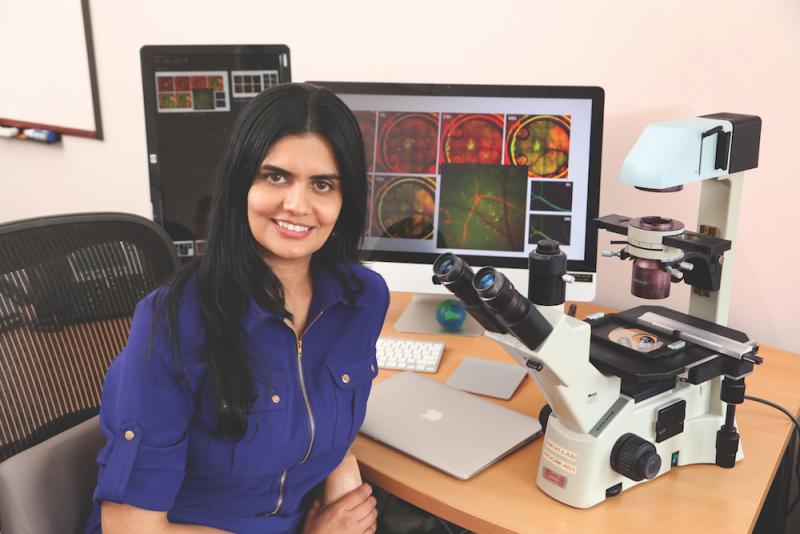

Most patients with IBC don’t have a single tumor mass that can be isolated and removed. Instead, the cancer appears as clusters of tumor cells called tumor emboli that infiltrate the skin and lymphatic vessels of the chest. “It’s highly diffuse, so that even if you collect the tissue, there are hardly any tumor cells in the biopsy,” says Devi, an associate professor of surgery and pathology. And, patients are treated with chemotherapy and radiation before surgery, which adds to the lack of tumor samples for research. Devi is developing better ways to sample, image, and understand IBC, enlisting help from researchers and clinicians in many other fields.

IBC is studied by only a handful of groups in the world, in part because it is rare. But it is the most aggressive form of breast cancer. IBC accounts for only about 6 percent of all breast cancers in the United States but causes 10 percent of the overall breast cancer deaths.

Because IBC is so dangerous—it resists treatment and easily spreads (metastasizes)—Devi thinks that what she learns can be applied to help fight other types of aggressive cancers. The

Department of Defense agrees; in August 2017, they gave Devi and collaborators a $1.9 million “Breakthrough Award” to study why some breast cancers are more metastatic than others, based in large part on her pilot research with IBC. Collaborators include Mark Dewhirst, PhD, and Greg Palmer, PhD, who provide expertise in imaging; Mike Morse, MD, who helps with identifying immune biomarkers; and Shelley Hwang, MD, chief of breast surgery, and Shannon

McCall, MD, Director of the Duke Biorepository and Precision Pathology Center, who work to increase banking of patient tumor samples.