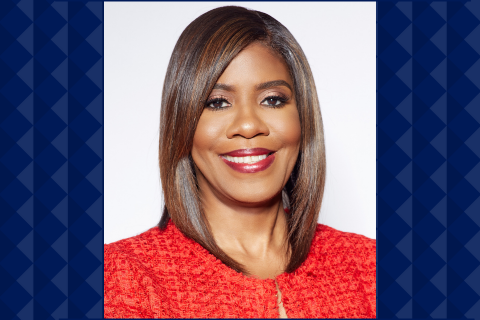

Patrice Harris, MD, MA, FAPA, a psychiatrist who served as the first African American woman president of the American Medical Association in 2019-2020, was inspired as a child to pursue medicine. Well into her medical career now, her experience is about as diverse as it gets: physician in private practice, adjunct university faculty member, public health administrator, patient advocate and medical society lobbyist, to name just a few of her roles.

On January 28, from 12 to 1pm, Dr. Harris will be presenting the annual James H. Carter, Sr. Memorial Lecture in the Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences. She’ll be discussing social determinants of health, racial and ethnic disparities, diversity within the medical profession and the work of the American Medical Association in these contexts. All are welcome to attend this event.

We recently spoke with Dr. Harris about her professional passions, her work with the American Medical Association and her upcoming lecture. Here are some excerpts from our conversation (edited for length):

Duke Psychiatry: What prompted you to branch out from practicing psychiatry—what fuels your passion in the many roles in which you’re engaged?

Dr. Harris: My original reason for wanting to be a physician was based on a television doctor, Dr. Marcus Welby. As a little girl, I saw that Dr. Welby not only took care of his patients inside the exam room, he cared about families and he cared about the community, all in the service of improving health. That broad vision of what physicians could do appealed to me from the very beginning.

Then fast forward to my last remaining days in my fellowship training at Emory, when I went down to our state Capitol. While I was waiting to talk to my legislator, I overheard a conversation—someone beside me talking to their legislator—and they were not giving accurate, science-based information about a medical issue. That experience cemented my passion for advocacy, for becoming engaged on a broader level.

And then I add my own lived experience with access to health care. I was fortunate: my mother taught school and my father worked on the railroad in West Virginia, so we had employer-based health insurance. But many of my relatives did not, and over the years, I saw them without health insurance, and certainly their health, suffered.

Duke Psychiatry: You’ve held a number of leadership roles in the American Medical Association, including Chair of the Board of Trustees and, most recently, President. What aspects of your work with the AMA are you most proud of?

Dr. Harris: First, I have to thank the wonderful team at the American Medical Association, because any success I’ve been able to have is a result of the full team at the AMA.

There are two things that stick out for me. The first is the opportunity to lead the AMA’s Opioid Task Force, because the opioid epidemic has been, and still is, a major public health issue.

The AMA has been able to really broaden the narrative around this issue so we can get to solutions that work. Sometimes in this country we look at complex problems through a narrow lens, and we focus too often on “feel-good” solutions that don't really make any impact on patient outcomes. For example, originally there was a one-size-fits-all solution to the opioid crisis: limiting the number of pills physicians could prescribe. The data show that solution didn’t really solve the problem; overdoses are going up. We didn’t really get to the root of the problem. Among many actions, we need to enforce parity laws, making sure there’s equitable access to evidence-based treatment for substance use disorders. In addition, administrative barriers that delay or prevent access to treatment should be eliminated.

Through the work of the Task Force, we’ve started to have meaningful conversations about getting to solutions around the overdose crisis—not just for opioids but also for other substances.

Another thing I feel really proud of is just showing up—being in the room, around those decision-making tables, where I was sometimes the only woman, and often the only African American, and was able to bring the lens of different lived experiences and a diversity of thought and opinion to the discussion.

Duke Psychiatry: What do you see as the most challenging issue for healthcare leaders in the next few years, and what’s one strategy you think could be effective in addressing that issue?

Dr. Harris: There are so many challenges. Certainly COVID has exposed some of the challenges that many knew: the health inequities that abounded, the lack of funding of our public health infrastructure and mental health infrastructure, how to move forward with technology to make sure we’re enhancing patient care and not exacerbating health inequities.

I prefer to think in terms of a framework for solutions to address any major health challenge. We should look at three broad areas. The first is that we should be intellectually honest. Secondly, we should make sure we are allowing the science and the evidence to drive solutions. And then the third is context, because none of these great challenges happen in a vacuum. They’re all interrelated. And I’ll just add one more critical piece: accountability. We have to develop metrics, hold everyone accountable to these metrics and continuously monitor and evaluate to make sure we are getting to the outcomes that we want.

Duke Psychiatry: In your upcoming talk at Duke, you’ll be addressing social determinants of health, racial and ethnic health disparities and diversity within the medical profession. Can you preview a few of your insights?

Dr. Harris: I will, of course, be talking about the data. I will be talking about solutions. And as we talk about health equity and issues around social determinants of health, we have to begin with truth telling. We have to be willing to examine our past, to examine the context and tell the truth. We have to be transparent. Truth telling and transparency is sort of a sub-focus of the work that we’re doing around vaccine hesitancy and why African Americans in particular have these issues.

After truth telling and transparency, we then have to be about the work of trust building. As we talk to communities that are impacted, we need to ask, “How can we show you that we are trustworthy?” We have to make a commitment to being in these communities.

We have to have uncomfortable conversations—racism, implicit biases, past discriminatory practices—before we can move forward.

Duke Psychiatry: What advice do you have for Black, indigenous and people of color (BIPOC) interested in pursuing a career in medicine?

Dr. Harris: One of the privileges of being the president of the American Medical Association, and leader in the AMA for several years, is the visibility. I hope that my visibility was tangible evidence to young girls and boys of color that they can realize their dream of being a physician, a leader. And so, my advice to them is, first of all, know that you can achieve your goals. Work hard. Be prepared. If this is your dream, work towards that dream.

But I also I tell students that while you are doing what you need to do, I’m going to do my best to continue to ensure that those of us who are leaders are doing our part to help make the path equitable for everyone who wants to become a physician—because I think we can all agree that, today, it is not. That goal is essential to the work of the American Medical Association and our new Center for Health Equity, and that will continue to guide my work going forward.

Want to hear more from Dr. Harris? Join us on Zoom at noon on Thursday, January 28.

This Q&A was first published in Duke Phsychiatry & Behavioral Sciences News