VIETNAM, 1970

Weeks after completing his Duke neurology residency, 29-year-old Dr. Marvin Rozear, peered through tangled barbed and razor wire at the edge of the U.S. Army’s 95th Evacuation (or “Evac”) Hospital, into the South China Sea. This hospital, a series of weathered Quonset huts, other scruffy buildings, latrines, sand-bagged bomb shelters, olive-drab trucks, jeeps, helicopters and other furniture of 20th century jungle war, stood near Da Nang, in what was then the Republic of Vietnam.

It was surrounded on three sides by plywood and corrugated iron huts housing thousands of impoverished Vietnamese displaced by the war. To the east, traditional fishing boats rode at anchor, framed by a few rocky islands. Rozear was the only neurologist in a thousand-mile radius. The 40-foot guard towers punctuating the perimeter did little to reassure the young specialist.

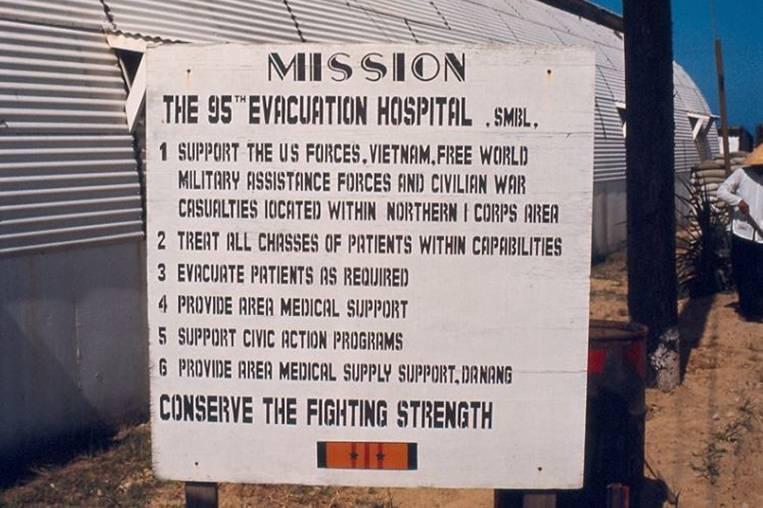

Rozear’s task was to treat neurological conditions for the thousands of U.S. troops, allied Vietnamese soldiers, military personnel of other nations, enemy prisoners of war, and Vietnamese civilians in the northern half of the country. "We treated everyone with no priorities except the gravity and urgency of their problems,” Rozear said. “It was a shock coming from the comfortable and equipped Duke Hospital, where I had backup in a flash when I needed it. In Vietnam, we lacked neurologic backup, faced primitive conditions, and faced patients I could not directly communicate with because of language and cultural barriers,” Rozear said.

Dr. Marvin Rozear photograph of the hospital during the Vietnam War

Dr. Marvin Rozear photograph of the hospital during the Vietnam War

U.S. military personnel needing surgery or other interventions could be flown to the Philippines, Japan, or the continental U.S. Rozear and his colleagues—mostly doctors freshly trained in their specialties--dealt with everything else. “I got immense support from our internists, radiologists neurosurgeons, and most adult specialties,” Rozear said. “But this was like being thrown into a cold lake having only read a book about swimming, with friends ashore reading from the same book and shouting advice.”