Medications used by astronauts on the International Space Station might not be good enough for a three-year journey to Mars.

A new study led by Duke University School of Medicine reveals that more than half of the medicines stocked in space, such as pain relievers, antibiotics, allergy medicines, and sleep aids, would expire before a Mars mission ends and astronauts return to Earth.

Astronauts could end up relying on ineffective or even harmful drugs, according to the study published July 23, 2024, in npj Microgravity, a Nature journal.

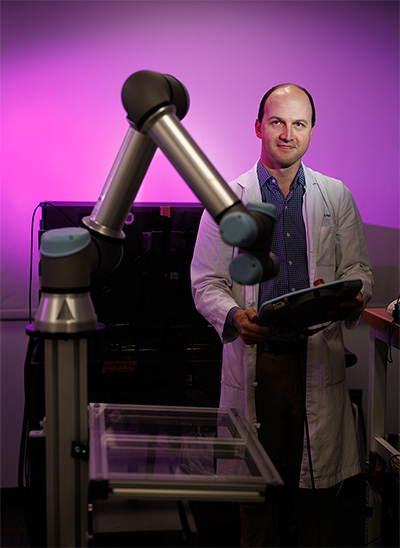

“It doesn’t necessarily mean the medicines won't work, but in the same way you shouldn’t take expired medications you have lying around at home, space exploration agencies will need to plan on expired medications being less effective,” said senior study author Daniel Buckland, MD, PhD, an assistant professor in the Department of Emergency Medicine at the Duke University School of Medicine and aerospace medicine researcher.

Unlike Earth, where a quick trip to the pharmacy can replenish supplies, astronauts will be isolated and reliant on whatever medications they bring with them.

Buckland collaborated with lead study author Thomas E. Diaz, a pharmacy resident at The Johns Hopkins Hospital, on the study that reveals medication expiration could pose a challenge as space agencies plan for long duration missions to Mars and beyond.

It’s the first time researchers have compared the medications used in space to a database of international drug expiration dates. The findings are concerning: 54 of the 91 medications had a shelf-life of 36 months or less.

Using the most optimistic estimates, about 60% of these medications will expire before a Mars mission concludes. Under more conservative assumptions, the figure jumps to 98%.

"A well-stocked pharmacy that is regularly resupplied, ... prevents small injuries or minor illnesses from turning into issues that affect the mission."

- Daniel Buckland, MD, PhD

The study did not assume accelerated degradation but focused on the inability to resupply a Mars mission with newer medicines. This lack of resupply affects not only medications but also other critical supplies, such as food.

NASA does not routinely disclose the types of medications on the ISS, where three to six crew members are always on board for what are usually six-month missions.

Diaz used a Freedom of Information Act Request to obtain information about the ISS formulary, assuming NASA would store similar medications on a Mars mission. At the time of the request, Diaz was a pharmacy student at the University of North Carolina Eshelman School of Pharmacy in Chapel Hill, NC.

“Tom reached out with the idea, knowing my work on risk mitigation for extended spaceflight,” said Buckland. “He was concerned that not enough research addressed the problem of medication longevity on a Mars mission.”

Buckland serves as deputy chair of the Human System Risk Board of the Office of the Chief Health and Medical Officer via an Intergovernmental Personnel Act agreement with NASA, where he evaluates the risk of spaceflight on humans and ways to mitigate that risk. As a faculty member in the Thomas Lord Department of Mechanical Engineering and Materials Science, Buckland has received funding from NASA to explore using robotics to deliver care in space.

However, NASA was not involved in the new study.

“Those responsible for the health of space flight crews will have to find ways to extend the expiration of medications to complete a Mars mission duration of three years, select medications with longer shelf-lives, or accept the elevated risk associated with administering expired medication,” Diaz said in the study conclusion.

After their expiration date, medications can lose their strength by a little – or a lot. Pharmaceutical companies assure a drug’s effectiveness until the expiration date on the package.

Increasing the amount of medications brought on board could also help compensate for lowered efficacy of expired medicines, authors said.

Getting Sick in Space: Real Risk

The stability and potency of medications in space compared to Earth remain largely unknown. However, the harsh space environment, including radiation, could reduce the effectiveness of medications.

Even with Earth-like stability conditions, most medications will expire before the Mars mission ends.

“Hopefully this work can guide the selection of appropriate medications or inform strategies to mitigate the risks associated with expired medications on long-duration missions,” Buckland said.

“Prior experience and research show astronauts do get ill on the ISS, but there is real-time communication with the ground and a well-stocked pharmacy that is regularly resupplied, which prevents small injuries or minor illnesses from turning into issues that affect the mission,” he said.

“Astronauts are human. Healthy and well-trained humans, but still humans doing a tough job in an extreme environment.”

Additional authors include Emma Ives of the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy and Diana I. Lazare of the University of Texas at El Paso School of Pharmacy.

Authors received no external funding for the study.

“Expiration Analysis of the International Space Station Formulary for Exploration Mission Planning,” doi.org/10.1038/s41526-024-00414-3