When Duke University School of Medicine students were pulled from clinical rotations on March 17 as a result of the COVID-19 global pandemic, Megan Brown felt lost. As a second-year student in the Duke Physician Assistant Program, she was in the middle of a women’s health rotation, looking ahead to graduation and contemplating her future career as a physician assistant (PA). Then everything changed.

“We were approaching the end of our [second] year and we were getting so excited,” Brown says. “We saw the light at the end of the tunnel, and it just came to a screeching halt.”

The second year of the PA program is dedicated almost entirely to clinical rotations. Due to the medical school’s decision to remove students from direct patient care, the second-year curriculum had to shift quickly to online training that would supplement the clinical training students had already received. This presented faculty with a challenge, and also an opportunity to get creative.

Quincy Jones, MSW, LCSW, MHS, PA-C

Quincy Jones, MSW, LCSW, MHS, PA-CAt the end of March, PA program clinical coordinator Quincy Jones, MSW, LCSW, MHS, PA-C, assistant professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, reached out to department colleagues in the Division of Community Health to brainstorm opportunities for the PA students, specifically around community health.

“We historically have had a community health elective that is not clinically-focused,” Jones says. “So when our students got pulled from rotations, I wondered what we could do virtually.”

Around the same time, Fred Johnson, MBA, assistant professor of family medicine and community health and vice chief for clinical services in the Division of Community Health, called Tara Blackley, MBA, MPH, deputy public health director of the Durham County Department of Public Health, to ask if they needed any help. And they did.

Every day, throughout the day, the health department receives confirmation of positive COVID-19 cases in the county, and case interviews are conducted to learn who the individual has been in contact with. Each case has a different number of contacts, based on their type of work, family situation or other factors. Blackley says the health department calls every contact, which is defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as someone who has been within six feet of an individual for 10 minutes or more.

According to the Durham County Coronavirus Data Hub, the county reported its first positive case on March 9. By April 1 the total had grown to 141, and the number of confirmed cases reported daily ranged from zero to 30 during that time period. With an increasing volume of contact tracing needs, Blackley expressed to Johnson that more staff was needed to assist the nurses who were making the calls seven days a week, as they could never predict what the next day would look like. Having more staff would allow the health department to scale up or down, as needed.

“One day you may have 10 cases and 70 contacts, the next 20 cases and 10 contacts, and the next five cases and 13 contacts,” Blackley says.

Johnson took this information back to his Division of Community Health colleagues to brainstorm the best way to assist the health department. An idea was formed, and an introduction was made.

Blackley and Jones spoke on April 8, and two weeks later the affiliation agreement was drawn up and a four-credit elective course was approved by the PA program’s curriculum committee. PA students would assist the Durham County Department of Public Health with case interviews and contact tracing.

“We have 13 students currently going to the health department for 30 hours a week each,” Jones says. “So they are contributing massively to the

PA Student Megan Brown

PA Student Megan Brown'A great way to give back'

After four weeks of virtual learning, Brown was interested in finding ways to help the community, so when the health department elective was created, she was eager to enroll.

“I thought this was a great way to give back, and also it would provide experience to see the other side of health care with the public health sector, because that’s something I really didn’t know much about,” she says.

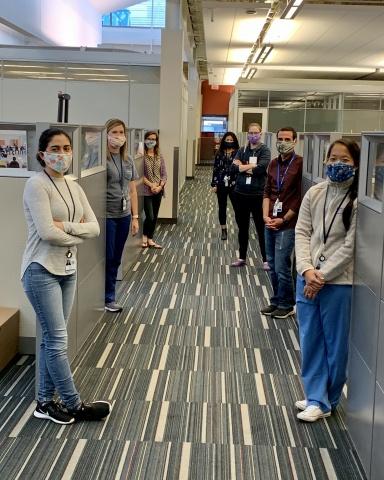

The PA students received training from the Durham County Department of Public Health, and work three to four 9-hour shifts a week, offering coverage seven days a week in a command center at the health department, located at 414 E. Main St. in Durham. They work directly with the health department’s medical services, communicable disease and environmental health teams and are assigned cases for the day. Brown estimates she is currently making about 10 to 15 calls a day.

The PA students conduct case interviews with the person who tested positive for COVID-19, get a list of names and phone numbers for those they have been in physical contact with, then call all those individuals to inform them they have come in contact with someone who tested positive.

“As you can probably imagine, people can be pretty upset,” Brown says. “They’re asymptomatic and we’re uprooting their world telling them that they need to be in quarantine for at least two weeks. We have to get the message across how important it is for them to follow the guidelines.”

The Durham County Department of Public Health also monitors everyone who tests positive. Brown says she and the other students are able to put their clinical training to work when making these calls by assessing symptoms and discussing any health care concerns the individuals may have. They sometimes advise people to seek help from a health care provider or even to call 911.

Blackley says the support of the PA students has helped the health department continue to operate at a high level, and she has particularly valued the two Spanish-speaking PA students who could assist with interpretation when needed.

“The individuals doing this work are not required to be medically trained, but having those qualifications has allowed the students to get up to speed and be more efficient in a shorter period of time,” Blackley says.

Brown says the experience has been invaluable for learning more about people’s perspectives and what social or economic factors may impact health. The PA program’s curriculum focuses heavily on teaching the social determinants of health and the program’s mission is focused on delivering equitable patient-centered care, but she says this elective has opened her eyes in a way that will better prepare her when caring for her patients in the future.

“Everyone has different challenges with this pandemic. Not everyone gets to work from home. They are worried about groceries. They are worried about picking up medications,” Brown says. “We assess their needs and make sure they have all the resources they need. And if they don’t, we connect them with people in the community who can help.”

Jones says while the students work their required hours at the health department, they are also doing online coursework for her, learning more about population health and community needs, and are participating in online discussions. And though the elective is set to finish on May 24, Jones says the health department elective will stay in the program’s curriculum for future classes, and the current cohort of students can continue volunteering at the health department through the summer if they choose to do so.

“The students are doing some really valuable work,” Jones says.

Blackley hopes the PA students will consider a career in public health after this experience.

“The students have been an incredible asset to the health department,” she says. “They have been engaged, eager to learn and incredibly supportive of the public health mission. Without the PA students, we would not have been able to continue contact tracing at the scale we were.”

Originally Published in Duke Family and Community Health News