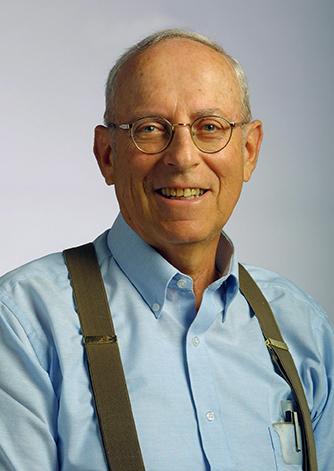

Biochemist Irwin Fridovich, the James B. Duke Professor Emeritus of Medicine and a familiar figure on the Duke campus for more than 60 years, died Saturday at age 90.

Fridovich was internationally known for his work on the body's responses to "free radicals," dangerously corrosive oxygen molecules that would cause serious damage to tissues if left unchecked.

Born in 1929 in New York City, Fridovich attended the Bronx School of Science and earned his undergraduate degree at City College in New York. He came to Duke as a graduate student in 1952, earning his Ph.D. in biochemistry in 1955. He joined the Duke faculty in 1961 and was promoted to full professor in 1971.

In the late 1960s, working with graduate student Joe M. McCord, who earned his Ph.D. at Duke in 1970, Fridovich discovered the enzyme superoxide dismutase (SOD) which living cells use to defuse a reactive form of oxygen called superoxide, now more commonly referred to as oxygen free radicals.

In a part of the animal cell called the mitochondria, an electron is stripped from oxygen as the first step in a chemical reaction essential to life, but that action leaves behind an oxygen molecule that is one electron short -- the highly reactive superoxide. This form of oxygen wants to find another electron and it will scavenge one from other molecules in the cell, including proteins and DNA, causing lasting damage, mutations and even cell death.

Fridovich’s discovery, superoxide dismutase, prevents that from happening.

Fridovich described the seminal experiments to isolate superoxide dismutases in a 2014 talk at Duke’s School of Medicine.

[video:www.youtube.com/watch?v=3DUD6SDzSPk&list=PLYZhPUaJyXIZDnCHPHHoSA8v3GmfJ…]

It all started with a gallon of fresh cow blood obtained from a local slaughterhouse.

“A heavy precipitate formed and (McCord) spun it down. All the activity was in the supernatant – yeah! So he says ‘what now?’ I said, ‘well add ammonium sulfate,’ that was a common thing then, ‘precipitate the enzyme.’

“So he adds ammonium sulfate, and he comes to me and says ‘I blew it. Look at this, it separated into two phases.’ He was all set to dump it down the sink and start over, and I said, ‘wait a minute, let’s assay both phases.’ And all the activity was in the organic phase. Wonderful. So what next?”

A few more steps led to a blue-green precipitate that was almost pure superoxide dismutase. “We were home free,” Fridovich recalled.

Fridovich and colleagues went on to reveal that superoxides are actually used as a weapon in biology. For example, the warriors of the immune system, cells called macrophages, use superoxide to attack and destroy invading bacteria. Consequently, many pathogenic bacteria carry defenses against the “oxidative burst” of these white blood cells, including superoxide dismutase.

Over the course of his career, Fridovich published more than 500 academic papers that have been cited more than 51,000 times. Six of his papers have more than 1,000 citations each.

Fridovich's and McCord's superoxide dismutase paper, published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry in November 1969, has been cited more than 9,300 times by other scientists and opened an entirely new field of medicine and biology devoted to oxygen free radicals. Today, anti-aging skin creams are sold that contain SOD, and grocery store labels tout the 'antioxidant' properties of various fruits and vegetables.

Duke colleague Jane Richardson came to Duke with her husband and research partner David Richardson in 1969, just as the superoxide dismutase paper was published. She said several members of the biochemistry department quickly turned their attention to characterizing various aspects of the intriguing new enzyme. The Richardsons, structural biologists who study the shapes of life's 3-dimensional proteins, eventually acquired SOD's shape in 1974.

"Initially, dismutase wasn't the sort of thing where everybody said 'oh, that's obvious, sure,'" Jane Richardson said. Fridovich had to patiently defend his finding for several years against a colleague elsewhere who insisted it was merely a copper storage protein. But the evidence became insurmountable.

Further work by Fridovich, McCord, and others in the years since revealed a much larger family of molecules that oxygen-breathing plants and animals use to scavenge potentially damaging free oxygen radicals.

Fridovich was a member of the National Academy of Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In 1997 he shared the Elliott Cresson Medal from the Franklin Institute with his former student, Joe McCord, for the discovery of SOD and pioneering the field of oxygen free radicals.

A devoted family man, Fridovich never missed a dinner with his wife and two daughters, one of which, Sharon Fridovich Freedman, is now professor of ophthalmology in the Duke School of Medicine. He always loved to spend weekends with the family, cutting and splitting firewood for his wood stove, tending his blueberry patch, hiking in Duke forest in cool weather and canoeing in the summertime.

He continued to go to Duke every weekday until about four months prior to his death, to read the latest scientific journals, and especially to enjoy a weekly lunch at Bullock’s BBQ with his best friend, K.V. Rajagopalan and colleagues.

Read the family obituary.