Speculation that a vaccine for COVID-19 might be widely available by the end of this year is overly optimistic, three Duke experts said Wednesday.

While there may be substantial scientific progress by the end of 2020, there will still be significant manufacturing hurdles to clear before a vaccine is available to most people, the experts said during a briefing for media.

Below are excerpts from the briefing:

ON DR. ANTHONY FAUCI’S RECENT TESTIMONY ABOUT A VACCINE BY THE END OF 2020

David Ridley, health economist

“Dr. Fauci is quite optimistic. I think optimism is good. I think optimism has a really important role. We need people within these companies being optimistic. If everyone sits back and talks gloom and doom … nothing’s ever going to get done. So I respect that optimism.”

“But will you and I get vaccinated this year? No way. It’s possible a vaccine will be approved this year. But not at scale. We won’t have a lot of doses of this.”

“We might have some people vaccinated this year. But the average person won’t be vaccinated this year.”

Thomas Denny, chief operating officer, Duke Human Vaccine Institute

“If you’re going into a tough game, you need a coach that’s getting the team revved up. We may have some good science by the end of the year and think we have some leading candidates. But manufacturing them to have it all administered, that’s a tall order to be ready by the beginning of 2021.”

Ooi Eng Eong, deputy director, Emerging Infectious Diseases Programme, Duke-NUS Medical School in Singapore

“Once we get to the efficacy phase and ask the question of whether this vaccine will work to prevent infection, that depends on how common the infection is at that time. If the situation still goes on as it is, we shouldn’t have any problem testing efficacy."

“But if for whatever reason the prevalence of the disease goes down, it will take us a much longer time to assess efficacy.”

“We’re not going to get rid of the coronavirus in a hurry. It’s going to stay with us. Even if we can vaccinate people, protect them from infection … the question is how long will immunity last?”

“If we think about using vaccines in stages, potentially we could get one, possibly at the soonest to me, about this time next year. Anything sooner than that is extremely optimistic. Others have said we could get it by the end of this year. I’m an optimistic person, but I’m not that optimistic.”

ON MANUFACTURING VACCINES ON A GLOBAL SCALE

David Ridley

“We’re preparing to manufacture at scale. Fortunately, some of these vaccine makers are already manufacturing now. Sanofi said they’re going to be able to make 100 million doses this year and a billion doses next year. That’s really unprecedented. Usually you’d wait to see if your vaccine is having some success. If you think there’s a 1-in-8 chance that you’re going to get on the market, and you’re already spending tens of millions, hundreds of millions of dollars, that’s kind of crazy. But that’s the crazy world we live in and I salute them for it.”

“Usually it takes years to manufacture. You want to be sure you got a good vaccine before you begin making it at scale. Typically this is going to take four or five years. Maybe now we can do it in one or two years. Part of this is going to depend on the appetite of these manufacturers to start building something now that they probably will never use.”

“My guess is this will take longer than people will assume because there will be a little bit of foot-dragging. If you drag your feet a little bit longer and make sure it’s a good vaccine, that it’s going to work before you make the huge investments in manufacturing, you can save a lot of money.”

ON LIKELIHOOD OF MULTIPLE VACCINES

Thomas Denny

“The duration of immunity post-vaccination is a major scientific issue we’re trying to understand. We’re also trying to understand right now what’s the duration of immunity after natural infection. That will help us probably understand how well or how well not vaccines will work for us.”

“One of the approaches we’re taking at the vaccine institute, we’re also exploring the potential development of a pan-coronavirus vaccine.”

“If we can develop a vaccine that would cover protection to all types of coronaviruses that may be a threat to us we think that would be a big benefit. That’s a longer-term goal for ours. It’s 18 months to two years out. I don’t think there are many playing in that space currently. Most are looking at the short-term COVID-19 pathogen and trying to get a rapid vaccine developed for that one.”

Ridley

“It’s very common for the second product, a later product to be better than the first. Lipitor was fifth to market for cholesterol drugs and was arguably better than the previous four.”

“It’s reasonable to expect that later entrants will be better. Assuming the virus is still with us and still a threat, I’d expect other companies to continue product development.”

ON VACCINE DEVELOPMENT COMPETITION

Ooi Eng Eong

“Obviously there’s pressure. There’s pressure from the demand from the public for a solution so they can go back to some level of normality in their lives. There’s pressure from colleagues in the hospitals saying we need to deal with this.”

“There’s also competition from other groups working on vaccines. I think competition is good. It forces us to think harder to come up with better, more innovative ways of doing things. There is pressure but I think at some level of pressure is good to really push the boundaries.”

ON SUPPLY SHORTAGES SLOWING VACCINE PROCESS

Ridley

“We need a lot of materials in this process. Some are very simple. Gowns and masks are pretty simple things. Swabs for diagnostics are pretty simple things. Rubber stoppers, medical glass sound pretty simple. But we really have a high standard for those because anytime we have something coming into contact with the vaccine that’s going to go straight into your blood stream, we have a really high standard for sterility.”

“Sterile water always seems to be in shortage. Water should be easy to make. But it has to be sterile because it’s going straight into the bloodstream. We can’t underestimate the importance of all these products along the line.”

“We might be a little concerned about hoarding. There’s cost to scaling up PPE. There’s cost to scaling up medical glass and rubber stoppers. Someone might hoard those. One of the vaccine manufacturers, one of the hospitals might try to grab those materials. There’s all sorts of parts in this process and if one of them breaks down, it slows the process of getting the vaccine to people."

ON VACCINE COSTS

Ridley

“None of the major vaccine manufacturers will charge ridiculous prices. They’re in this game to try to do good, to try to impress their employees, to try to impress their shareholders. They’re not going to do that by charging ridiculous prices.”

ON A VACCINE’S POTENTIAL USE AS A THERAPY AS WELL

Ooi Eng Eong

“We’re testing (our vaccine) as a preventative vaccine. But is an intriguing possibility. Our fight against the virus relies on the body to recognize first of all it’s infected with the virus. It triggers a series of processes. So it is entirely possibly theoretically that because we’re using an RNA vaccine, the vaccine will trigger the processes that will allow the (body) to fight an RNA pathogen.”

“We’ve only had this virus for seven months now. There’s a lot we don’t know about this virus.”

“Think about it like a thief breaking into your house. If this person is very skilled at overcoming your alarm, they will be able to break into your house. If you have another system that can activate the alarm while the break-in is in process, you would actually trap the thief. So it is something that is possible.”

ON WHO SHOULD GET VACCINATED FIRST

Denny

“Those with underlying medical conditions, and first-line responders. Hospital workers, they’re the highest priority. If we can’t keep those folks going, we’re in trouble.”

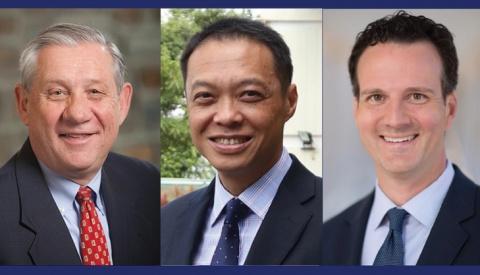

Faculty participants

Thomas N. Denny

Thomas Denny is chief operating officer of the Duke Human Vaccine Institute, a professor of medicine and an affiliate member of the Duke Global Health Institute. His administrative oversight includes a research portfolio of more than $400 million. Denny has served on numerous committees for the NIH over the last two decades.

thomas.denny@duke.edu

Ooi Eng Eong

Ooi Eng Eong is a professor of medicine and deputy director of the Emerging Infectious Diseases Programme at Duke-NUS Medical School in Singapore. He also co-directs the Viral Research and Experimental Medicine Centre at the SingHealth Duke-NUS Academic Medical Centre (ViREMiCS), which studies therapies and vaccines against viral infections.

engeong.ooi@duke-nus.edu.sg

David Ridley

David Ridley is a professor of the practice at Duke’s Fuqua School of Business, where he is faculty director of the Health Sector Management program. He was lead author of the paper proposing a review program to encourage development of drugs for neglected diseases that became U.S. law in 2007.

david.ridley@duke.edu

This article was originally published in Duke Today