The day her eyelashes froze together turned out to be a pivotal day for Heather Whitson, MD, HS’01-’04, ‘06. She was a medical school student at Cornell University at the time, spending the winter in Boston doing research with a Harvard geriatrician. She was enjoying the research so much she was hoping to do her residency at Harvard so she could continue it. But when her eyelashes froze, she started dreaming of warmer climes.

“At that point I asked [my mentors at Cornell and Harvard], ‘If you wanted to do geriatric research and be someplace with warmer winters, where would you go?’” says Whitson. “They both immediately said, ‘Duke’ and ‘Harvey Cohen.’ And it wasn’t just Duke, it was Harvey Cohen.”

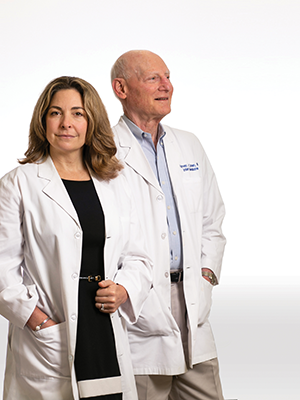

So she headed to Duke for her residency, and she has been here ever since. Today she is an associate professor in medicine and ophthalmology.

And this summer, she became the new director of the Duke Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development, taking over the reins from Harvey Cohen, MD, HS’65-’67, ’69-’71, who stepped down after 37 years on the job. Although Cohen vacated his corner office for Whitson, he isn’t retiring from the faculty just yet. He has moved into her old office and is continuing to mentor, teach, and do research.

Cohen, like Whitson, came to Duke to do a residency and never left. The Walter Kempner Professor of Medicine, he is considered a pioneer in geriatrics and has been instrumental in positioning Duke as a national leader in the field. He has held many leadership roles at Duke over the years, including chair of the Department of Medicine and founding chief of the Division of Geriatrics.

“I would be way more terrified stepping into this new role if not for the fact that Harvey is not retiring,” Whitson says. “One of the things that he has taught me is that you never outgrow the need for wise advice.”

For his part, Cohen has full confidence in Whitson. “I’ve mentored Heather for years and have been delighted to see her develop in her career and her research,” he says. “She’s ready for leadership.”

SOLVING THE PUZZLES OF AGING

Whitson has been drawn to older people her whole life. As a child and teenager, one of her favorite activities was visiting nursing homes. As an undergraduate at Stanford, she loved volunteering in the Alzheimer’s unit at the VA hospital. She particularly remembers a man who always mistook her for his wife. “I was fascinated by what was going on in this man’s brain,” she says. “What circuits were supporting the things he remembered from years ago but failing to function in so many other domains?”

During her internal medicine residency at Duke, she gravitated toward older patients. She says, “When there was an 89-year-old who was weak or dizzy in the ER, people were like, ‘Heather’s going to be so excited to help this person.’”

Part of the intrigue was the complexity that older patients often presented. “What I like about internal medicine is the puzzle of trying to sort out what is causing the symptoms and what’s the right thing to do about it to help the patient,” she says. “The puzzle is so much more complex and interesting in an older person who may have a lot of medications and conditions and age-related impairments in their body.” Today, Whitson’s research centers on the intersection between cognitive decline and sensory loss, particularly low vision. She’s interested in how the two interact both on a functional level and physiologically. Functionally, having low vision and cognitive decline add up to significant disability—it’s harder to find things if you can’t remember where you put them and also can’t see well.

There is evidence that the two interact physiologically as well. Low vision co-occurs with cognitive decline more often than chance would suggest. Are there similar biological mechanisms behind seemingly disparate conditions like age-related macular degeneration and Alzheimer’s disease? Or does reduced sensory information put extra stress on a brain already beginning to struggle with reduced cognitive function? Whitson is continuing to tease out the interrelationships between the two. She’s also increasingly adding in a third concept—resilience.

“When an older brain loses vision, it doesn’t have the plasticity to compensate in the way that a younger brain would, and people underperform,” Whitson says. “We’re trying to understand how we can help older people be more resilient in the face of a stressor like that.”

-Heather Whitson, MD

TAKING THE BROAD VIEW

Resilience—the ability to retain or regain function after a stressor—is a big theme of the Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development (commonly referred to as the Center for Aging). Stressors accumulate as people age—a new diagnosis, the loss of a spouse, moving out of the family home. Because stressors can be both physical and emotional, the center takes a broad view of resilience, applying the concept to psychological, social, physical, and cognitive aspects of aging.

Taking the broad view comes naturally to the interdisciplinary Center for Aging, which was established in 1955 as one of five such centers funded by the Office of the Surgeon General.

The center houses two long-running grants from the National Institute on Aging (NIA): a Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center and a postdoctoral research training program. The Pepper Center, led by geriatrics professors Kenneth Schmader, MD, HS’86-’88, and Miriam Morey, PhD, focuses on research related to physical resilience. The postdoctoral training program provides two years of research support and mentorship to three newly minted PhDs or MDs each year.

In addition to these two grants, the Center for Aging administers many investigator-initiated grants worth significant funding each year.

The center’s 128 senior fellows include academic clinicians and PhD scientists of all stripes, from social sciences to biological sciences. These investigators generate knowledge about stressors and resilience in late life on many fronts, including nutrition, physical activity, social support, the immune system, and the interplay of genetics and life experience.

They are also investigating models of care in the medical system that can help older people recover better from surgeries, falls, and other physical setbacks.

And social workers at the Duke Dementia Family Support Program, run through the Center for Aging, provide support groups, newsletters, and educational programming for North Carolinians with dementia and their families. “The Family Support Program is looking at the stressor of dementia and trying to promote resilience in light of that diagnosis by supporting caregivers and patients in a social way,” Whitson says.

PEARLS OF EXCELLENCE

Going forward, Whitson wants to grow the center’s capacities in Alzheimer’s disease research. “There is a lot of institutional interest and momentum right now in Alzheimer’s disease, and we are perfectly positioned to really contribute to those efforts,” she says.

Her five-year goal is to land a federally funded grant for an Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center. One of the first steps in that direction will be to showcase existing data and programs, such as Duke’s Joseph and Kathleen Bryan Alzheimer’s Center, under one institutional umbrella.

“Duke has all these little pearls of [Alzheimer’s] excellence, and my job is to string them into a necklace that meets the expectation and requirements of a federally funded center,” she says.

Another goal is to strengthen ties with the social sciences on the university side to continue to inform research into psychological and social stressors and resilience, as well as health policy. “A lot of the changes that will be important to health policy over the next 20 years will involve the aging population,” she says. On this front, Whitson is anxious to collaborate with Duke’s Margolis Center for Health Policy.

In fact, Whitson is enthusiastic about collaboration, period.

“We are always open for collaborative opportunities,” she says. “So many of the diseases and outcomes that all of us study are age-related in some way or other—maybe the aging process affects the disease or maybe the outcomes that matter most change with age. There could be a new angle for your research that we could help with.”

The center can also provide expertise in how to recruit and retain older adults in clinical trials, or how to incorporate questions related to aging into studies of younger people.

“There is a common misconception that if we study aging, we’re only interested in late life,” Whitson says. “But the problems that we see in late life frequently have their roots much earlier in life. The aging process begins from the moment you draw your first breath.”