See all talks from Duke researchers and Durham community partners on the forum website.

In North Carolina, Hispanics and Blacks are contracting COVID-19 at disproportionate rates relative to their representation in the population, and Blacks are dying of COVID-19 at higher rates.

A panel of Duke University researchers and Durham community partners met recently in an online public forum to discuss the social, biomedical, and healthcare drivers behind these disparities and what can be done to help those impacted.

More than 1,100 people attended “A call to action: Identifying next steps to address biomedical, health care, and social drivers of COVID-19 disparities” which was sponsored by the Duke Clinical and Translational Science Institute, Duke Center for Research to Advance Healthcare Equity (REACH Equity), Duke Social Science Research Institute, and the Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity.

“COVID-19 has highlighted challenges for vulnerable populations. We know that the virus has not impacted everyone in our community the same even though we like to say we are in it together,” said Mary E. Klotman, MD, dean of the Duke University School of Medicine, in her opening remarks. “Duke is committed to work to address these inequities amplified by COVID-19 as a team effort with our community partners and with our partnering institution North Carolina Central University.”

Along with presentations from researchers from the School of Medicine and across campus, the forum also featured talks from Joanne Pierce, Durham County General Manager of Health and Well-being for All; Clarence Birkhead, Durham County Sheriff; Ben Rose, director of the Department of Durham County Social Services, and other leaders of regional and state social programs designed to serve minorities.

Kimberly Johnson, MD

Kimberly Johnson, MDDuring her morning keynote talk, Kimberly Johnson, MD, associate professor of medicine and director of Duke’s REACH Equity Center, shared startling statistics from both the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services and the American Public Media Research Lab.

At the time of the talk, In North Carolina, Hispanics represented 10 percent of the state’s population, but 32 percent of COVID-19 cases and four percent of COVID-19 related deaths. Blacks represented 22 percent of the state’s overall population, but 32 percent of COVID-19 cases and 35 percent of COVID-19 related deaths.

While Hispanics are contracting the virus at the most disproportionate rates, Blacks are dying of COVID-19 at the most disproportionate rates, according to the data. The increased risks of exposure and poor outcome for minorities have to do with social drivers that have been in place for centuries, said Johnson. Minorities’ risk of exposure is increased due to structural racism in societal infrastructures like healthcare, employment, housing, education, and criminal justice.

“Racial and ethnic minorities have lower incomes, lower levels of wealth, so as a result they’re more likely to live in crowded multi-generational households,” said Johnson. “They have increased representation in the high-contact jobs where we’ve seen increased risk—food services, transportation, retail. Because of their overrepresentation in these jobs they may be less likely to have paid sick leave or flexible work arrangement, and the ability to work from home remotely is really a privilege.”

Furthermore, minorities are “more likely to use public transportation and to live in neighborhoods where there may be higher risk of exposure related to higher densities of populations or other disadvantages.”

“So what does this mean?” Johnson asked. “Well, the number one way we’re taught to limit our exposure is through social distancing, and all of these factors lead to a decreased ability to adhere to these guidelines.”

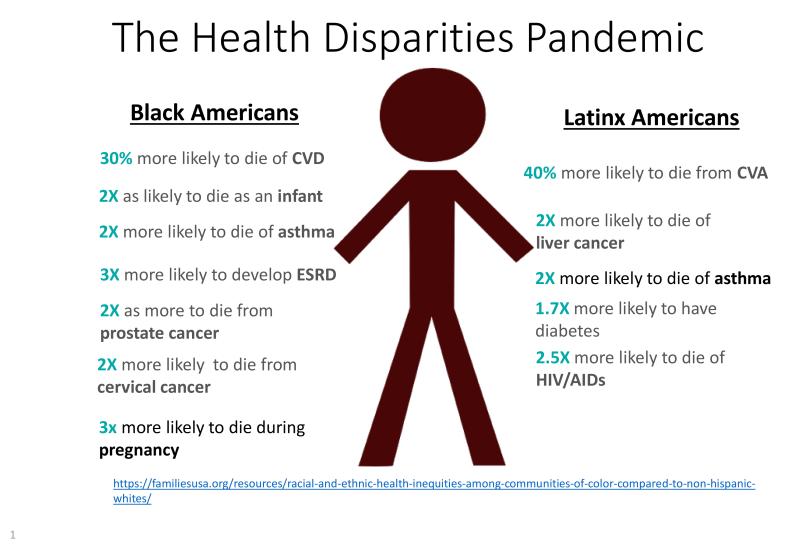

Meanwhile, the poorer outcomes that COVID-19 infected Black Americans face may also be related to a disproportionate rate of co-morbidities which can complicate and exacerbate COVID-19 symptoms, said Johnson. Black Americans are more likely to suffer from asthma, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, hemoglobin disorders, and chronic liver disease. This disproportionate rate of disease relates back to the fewer opportunities that Black Americans have to achieve optimal health and well-being based on factors such as wealth and health insurance, she said.

Ebony Boulware, MD, vice dean of translational sciences in the Duke University School of Medicine and director of the Duke Clinical and Translational Science Institute, said the forum was intended to be an opening conversation. A follow-up forum will be held in August 2020.

“This is a call to action. As we all know, COVID-19 has brought its own health disparities in and of itself but it has also exacerbated existing disparities that have existed for some time in our society,” said Boulware.

“So, we’re really here to identify causes, consequences and solutions to the disparities that have been exposed by COVID-19. Our hope is that we have a chance to spark a dialogue about this serious situation. And we hope that this symposium will spur partnerships, innovations and strategies for solutions.”