Drug appears to reverse structural and genetic brain changes that affect memory, learning

A drug used to slow cognitive decline in Alzheimer's disease could offer clues on how drugs might one day be able to reverse brain changes that affect learning and memory in teens and young adults who binge drink.

In a study led by Duke Health and published in the journal Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, scientists demonstrate in rats that a short duration of the drug donepezil can reverse both structural and genetic damage that bouts of alcohol use causes in neurons, or nerve cells, in the young brain.

There is limited research on the extent to which alcohol effects the developing brain in teens and adolescents, but it's evident that drinking during adolescence causes changes in the brain. Much of the research has looked specifically at the hippocampus, which is linked to learning and memory. Whether those changes are permanent is unknown.

"Clinical studies are starting to show that adolescents who drink early and consistently across the college years have some deficits in learning and memory," said senior author Scott Swartzwelder, Ph.D., professor in psychiatry at Duke. "It's not a sledgehammer -- it's not knocking their memory out completely -- but there are demonstrable, if subtle, effects on their cognitive function."

Because they can't ethically subject youth to alcohol to study its effects, researchers use the developing brains of rats to understand the effects of "intermittent alcohol exposure" -- the equivalent of drinking to a blood-alcohol level of .08 (the legal limit for driving while impaired) three or four nights a week.

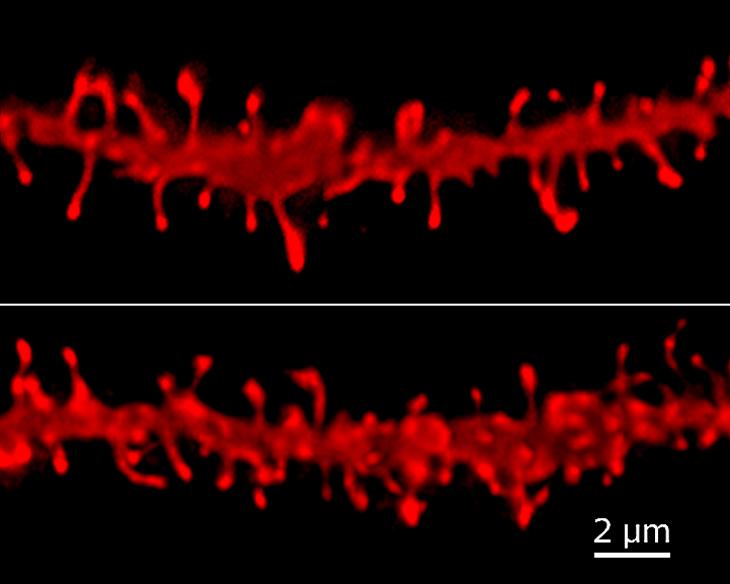

When researchers examined neurons in the brains of adult rats that had been exposed to alcohol when they were adolescents, they found far fewer dendritic spines, which resemble leggy mushrooms stemming from neurons to receive information. What looked like a dense forest of dendritic spines in healthy rats had been reduced to sparse, stubby structures in those previously exposed to alcohol.

"Any change in the density of spines on dendrites tells you those cells are processing information differently than they should be, and whether that processing goes up or down can be a problem," Swartzwelder said. "They need to be just right. Downstream, these changes can throw a monkey wrench into how cells function. You can imagine how quickly that could multiply in a region of the brain where you've got millions of cells interacting."