Return to 2021 Alumni Magazine

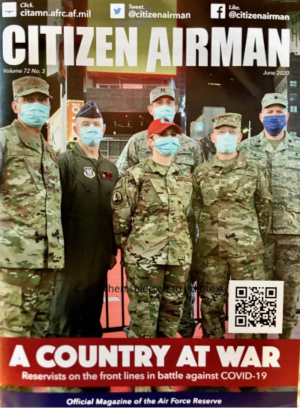

Alex Steele, MHS, PA-C (’02), never imagined he’d work on the front lines of a global pandemic. He specializes in orthopedic surgery, but as a member of the Air Force Reserves, was mobilized to New York City in April 2020 to assist overwhelmed hospital staff caring for COVID-19 patients.

“Being an orthopedic PA primarily, I didn’t really have a lot of background with intensive care, but you have to do what you have to do,” he says. “When we got there, every floor of the hospital had been converted to an ICU, and 98 percent of patients were COVID-positive. There were around 150 to 160 people on ventilators.”

Though Steele was more accustomed to working with orthopedic patients, he was able to translate those skills to care for those suffering with COVID-19.

“I found a little niche working to provide airway management,” he says. “I worked with an intensive care doctor, and we formed prone teams. It is pretty well known that if you prone patients, putting them on their belly, it results in improved oxygenation.”

That kind of versatility has made graduates of the Duke Physician Assistant Program critical in the response to the COVID-19 pandemic. From clinical environments to research and administrative roles, Duke PA alumni have worked tirelessly for more than a year around the world to meet the challenge of an unprecedented global health crisis.

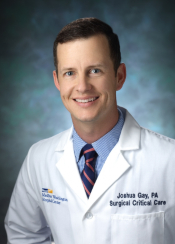

Josh Gay, MHS, PA-C (’12), knows well the pressure of pivoting to meet the needs of an ICU environment. Working in the surgical ICU at Washington Hospital Center, a level-one trauma center in the nation’s capital, Gay normally serves in the lead position in the cardiac surgery ICU with a yearly three-month stint in the general surgical or neurological ICU. But when COVID hit D.C., Gay was forced to shift priorities to meet the demand of virus patients.

“Everything changed,” he says. “We were asked to open new ICUs. We were asked to repurpose and re-create ICUs to be fully COVID-dedicated during our biggest surge in the spring.”

While reallocating resources, Gay and his colleagues also had to rethink how they provided patient care, particularly when dealing with the families of patients.

“The biggest thing that has changed is not having families present and not being able to communicate with them and doing it over the phone,” he says. “Family members being able to see their loved ones in the bed better articulates how they are than me telling them—that’s been a huge challenge to make families understand how sick their loved ones are.”

For Chad Eventide, MHS, PA-C (’11), those challenges are compounded by language barriers and a lack of resources. He works for the U.S. Department of State as a foreign service medical provider in Dushanbe, Tajikistan, providing care for diplomats, embassy staff and their families.

“It’s the capital city, but it’s very much lacking in medical resources,” he says. “We don’t have much in the way of specialty intensive care—it’s pretty rustic medicine out here.”

During the pandemic, Eventide has cared for patients with the virus, along with managing contact tracing and providing public health guidance for the embassy. And with limited resources, he also facilitates medivac transports via air ambulance or commercial planes for patients with severe cases of the virus to get the care they need in a neighboring country.

“I work so far flung from any proper hospitals or clinics or anything,” he says. “It’s a different kind of medicine that I do, working with little in the way of resources, and Duke prepared me with the skills and training to do that.”

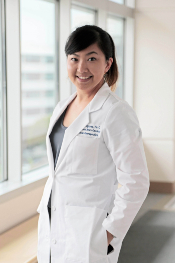

A shortage in resources inspired Minh Nguyen, MHS, PA-C (’13), to step up during the early months of the pandemic. She works primarily in neuro-oncology at Providence St. John’s Health Center in Santa Monica, Calif., and when the call for assistance on clinical trials for COVID-19 treatments went out, Nguyen answered.

“Working in neuro-oncology, by default I already do a lot of clinical trials,” she says. “When these trials came about, they were looking for anyone to help because they didn’t have manpower yet.”

Nguyen worked on the Regeneron Pharmaceuticals trial of Bamlanivimab, an investigative treatment for COVID-19 in non-hospitalized adults and adolescents with mild-to-moderate symptoms at higher risk of developing severe symptoms. She also worked on the convalescent plasma program, which involves the use of blood donated by patients who have recovered from COVID-19.

Though she’s no longer working on those specific trials, Nguyen says COVID-19 has still had a major impact on her day-to-day job. With infection rates hitting critical highs in Los Angeles during and after the holidays, Nguyen and her colleagues had to adjust the way they care for their vulnerable patients to mitigate the risk of transmitting the virus.

“We see patients in an ambulatory setting in the hospital because a lot of them get infusions of chemotherapy or biotherapies, and the risk is high for exposure,” she says. “We’ve had to adapt the way we do things. We’re a group of four doctors and three PAs, and we have figured out how to rotate one PA at the office not seeing patients for a week and then two in the clinic.”

The rotation—coupled with instituting virtual appointments for any patients not receiving infusions—helped the team to ensure they could keep their patients safe while providing uninterrupted care.

“That was our biggest concern—how to protect our patients from our exposure, and if we are exposed, how to not cancel a whole clinic because of quarantine,” Minh says. “Those strategies came into play.”

That kind of strategic approach to patient care has been a major part of the post-clinical career of Susan Edgman-Levitan, PA (’77). The 1977 alumna currently serves as executive director of the Mass General Stoeckle Center for Primary Care Innovation in the Division of General Internal Medicine and as co-chair of the Mass General Brigham Patient Experience Leaders Committee.

In those roles, Edgman-Levitan focuses on patient experience in the health system—which is the largest in New England—collecting data and creating internal benchmarks and protocols to improve the patient experience. And once the pandemic hit, Edgman-Levitan and her team pivoted to focus on the changing nature of clinical visits.

“COVID really hit Boston hard starting in late February 2020, and we shifted from doing 10 percent of our visits via telehealth to almost 90 percent,” she says. “Since then, we’ve done almost a million and a half telehealth visits. We decided immediately that we had to collect data from our telehealth visits just like an in-person visit. We now have a fair amount of data on what their experiences have been like with telehealth.”

Edgman-Levitan also has been involved in engagement work in Mass General’s Division of Palliative Care and Geriatrics, working to drive home the importance of selecting a health care proxy and understanding that person’s role and what information they’ll need to perform it.

“Because we know many people do not have a health care proxy, and at this time no one knows if they’re going to end up in the hospital or in the ICU, imagine how hard it is to have these critical conversations if everyone on the care team is wearing masks and all this protective gear,” she says. “We will now be able to offer a platform for our patients where they can identify a health care proxy virtually, get it witnessed virtually and accept it as a legal document.”

Edgman-Levitan says that with an unpredictable, deadly virus, these decisions are more important than ever.

“It’s not a decision about, ‘I’ll have two antibiotics and one ventilator,’ it’s about the balance of longevity versus quality of life,” she says. “Those aren’t things you just think about and you’re done—people’s values change over time.”

For Edgman-Levitan, doing this important work wouldn’t be possible without her foundation at Duke and the versatility of the PA profession.

“The smartest thing I ever did was become a PA,” she says. “It gave me such an incredibly strong clinical foundation and understanding of health care, but it also gave me the flexibility to pursue many other different interests I have. And I’m not sure I’d have felt comfortable deviating and going down these different paths if I’d trained in one field.”

And during a global health crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic, the ability of Edgman-Levitan and her fellow PAs to not only step up, but also adapt to meet a need, has made the difference between life and death for so many patients.

“PAs are people who just want to make a difference,” she says. “Almost every PA I’ve ever known is someone who cares deeply about making a difference and making sure people get the health care they need.”

Jennifer Bringle is a freelance writer based in Greensboro, N.C.

Return to 2021 Alumni Magazine