Tiffany Adams, PT, DPT, MBA, PhD, provided an up-close view of a rare group of physical therapist educators as part of the Interdisciplinary Rehabilitation Research Seminar Series on Oct. 18.

Dr. Adams, director of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion for the Duke DPT program, presented PT Unicorns – Exploring the Lived Experiences of Black Female Physical Therapy Faculty in the U.S. to attendees at the Interprofessional Education Building (IPE) and online.

She calls them PT unicorns, and for a good reason: there are 101 Black core faculty working among the almost 300 PT programs in the U.S. that are accredited or seeking accreditation. Ultimately, about 3 percent of all core faculty in PT education are Black, and 4.4 percent are Black program directors, according to the latest data from the Commission on Accreditation in Physical Therapy Education.

When you narrow it down to Black female faculty, the number goes down to double digits.

“Unicorns are the perfect metaphor to capture the experiences of Black female PT faculty. We meet student, programmatic, and institutional needs in very unique and valuable ways, while simultaneously navigating unique barriers and challenges within these same spaces that we add value to,” Dr. Adams explains. “The intersectionality of race and sex/gender can help contextualize why our experiences are unlike those of many of our peers.”

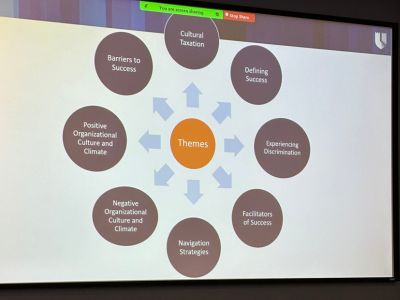

For her doctoral dissertation, Dr. Adams conducted semi-structured interviews to explore participants' lived experiences representing 10 PT education programs. Dr. Adams shared various findings, including broad incidences of discrimination, cultural taxation, and barriers to success that impacted participants’ teaching, research, and service. Most participants disclosed experiences in the form of covert discrimination, disrespect, hegemonic practices, and invalidation and/or isolation from peers and students.

Participants also identified external barriers to success, including hierarchy, hiring practices, lack of representation, support, power and privilege, and silos.

“Imposter syndrome was the only internal barrier to success identified across the group, and interestingly, that transcended participants’ years of experience,” she explained. “And when you look at the research in the area of imposter syndrome, specific to racially minoritized groups, a lot of times it's tied to racialized stereotypes that are assigned to those groups, as well as, unfortunately, some internalized racism.”

Dr. Adams said that some participants described instances of internalizing racial stereotypes in a way that forced them to question their behaviors.

“They would say, ‘Maybe I believe what people have been telling me my whole life,’” she said. “It’s unfortunate, but it does happen, and it is a form of racism in our society.”

Some of the participants experienced cultural taxation in the following ways:

-

Many were expected to serve on DEI committees and workgroups. “Sometimes it was an internal expectation, ‘I feel like I need to do this because I didn’t have this as a student, and I must help move things in a more positive direction.’ Sometimes it was programmatic expectations and just putting people on committees because of how they identify,” she said.

-

Several participants reported the expectations of mentoring and supporting underrepresented minority students. “One person shared, ‘I have my official advisees – but then I also have everyone else’s advisees from racially minoritized backgrounds because they want support as they navigate some of their identity-specific experiences,” said Dr. Adams.

-

Many interviewed for the study were expected to be the primary person in the program who speaks up when there are racial issues and/or incidents. Specifically, one participant described cultural taxation as “Being always expected to be the one who always says something when a racialized incident happens in the U.S. Or being the one to always question a policy if something feels like it is disparately impacting a group of students,” she explained.

Positive Experiences

Several participants shared their positive experiences in building a community of support. Others shared the unique ways they’ve navigated their professional environments to facilitate their success.

Several individuals shared feelings of being appreciated and having autonomy. All participants expressed the benefits of mentorship, yet many reported not having the support of their peers and their program directors or department chairs. Few participants identified that they work in environments that are actively confronting racism and the positive impact that this attention was having on their personal and professional experience. However, most participants described working in professional spaces that avoided difficult conversations and were silent about racism when witnessed and reported.

Several participants reported instances of disengagement as a navigation strategy to maintain their mental health and promote their success. Disengagement was often described as “going to work, doing my work, and going home” to distance themselves from uncomfortable or toxic environments.

Another participant that Adams described learned to leverage her peers’ power and privilege by having a “pre-meeting” before the actual meeting with a White male faculty member to share an idea that he can introduce in the full faculty meeting to get things moving in a positive direction because he was more likely to be heard than she was.

Other Black female faculty shared their instances of overcompensation and overachievement. Several said that they have pursued numerous academic credentials and degrees.

“That resonated with me. I have four degrees, and it wasn’t necessarily for personal validation each time. It was so that I could say, ‘Well, that won’t be the reason you don’t give me a seat at the table,’” said Dr. Adams of her career choices. As a result, many participants were more educationally accomplished, on paper, than their White colleagues. Yet, they were often still not given a seat at the table.

Several participants pointed out the negative impact of performative activism and the need for their programs and institutions to follow through by committing to resources needed to achieve DEI goals. One person said, “We have diverse students, but we are not willing to go the extra mile regarding resources to support them and ensure they are successful.”

“I think this is a critical point. As we think about our attempt to diversify our student body and our faculty, (we need to) make sure our environments are ready for the different needs that emerge when we do that,” Dr. Adams said.

In concluding her work, Dr. Adams offered Recommendations for Leaders and Faculty in PT Education.

-

Realize and appreciate the unseen contributions and experiences of Black female faculty in their programs.

-

Actively address workplace discrimination experienced by some Black female faculty. Upstanding is powerful; avoidance and silence are harmful.

-

Disaggregate faculty outcomes data to explore racial and gender inequities.

-

Formalize peer mentorship models and peer networks to address the lack of access to resources and challenges navigating academia. Acknowledge the systematic causes of these challenges.

-

Provide intentional, early, and proactive promotion and tenure support.

-

Develop accountability structures related to programmatic culture and climate (climate is co-created by everyone in a program or institution, whether positively or negatively, so we should all be held accountable).

-

Promote formal and informal communication pathways with leadership.