A combination of a gene and daily-life stress contributes to disease risk in both Black and white women, but the stressors are different between the races

A genetic variation in combination with the stress of racial discrimination appears to increase the risk of metabolic and cardiovascular diseases among Black women, according to a recent study from Duke Health researchers.

The finding builds on a similar gene-based association the researchers reported in white women, but curiously did not find among Blacks. The gene and stress-based disease risk emerged when researchers applied a dataset of lifestyle and environmental factors that included racial discrimination.

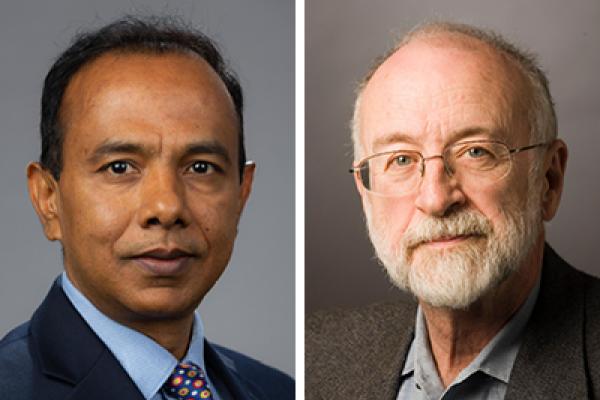

“One of the possible reasons for not originally finding this risk in Black samples was that the stress measures may not have been sufficient to capture the stress in everyday life among Black participants,” said Abanish Singh, Ph.D., assistant professor in Duke’s department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences and lead author of the study appearing Oct. 19 in the journal Translational Psychiatry.

For the current study, Singh and colleagues revisited the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), which was used in the original research reported in 2014, plus nine additional datasets to amass more than 28,000 Black and white participants.

Two of the datasets specifically inquired about stress from financial strains, relationship or marital problems, difficulties with job or ability to work, serious health problems of spouse or someone close, and one’s own serious health problems. One of the studies, the Jackson Heart Study, also included whether racism/discrimination, neighborhood issues, legal problems or unmet basic needs contributed to stress.

The other studies yielded that information through proxy indicators, where survey recipients responded to inquiries about whether work, finances, marital conflicts or health problems caused stress.

The scientists then identified study participants who carried a variant in the EBF1 gene. Black women who had the variant and also indicated higher stress levels that included the impacts of discrimination had higher risks of obesity, diabetes and/or cardiovascular disease.

“What we have found now with both the white and Black women is that it’s not genes OR the environment, its genes AND the environment,” said senior author Redford Williams, M.D., professor in Duke’s departments of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science, Psychology and Neuroscience, and Medicine.

Williams and Singh said the study provides a way to identify women who have this risk and target them with interventions that could reduce stress.

“The promise of precision medicine is to find predispositions to health issues before they arise,” Williams said. “This work is a step in that direction.”

Singh said the study also demonstrates that health issues share commonalities, but also psychosocial differences that require careful analysis.

“Our hypotheses were focused on the following problems: a failure to observe a significant EBF1 gene-by-stress association in Black samples; a significant association only in a specific subgroup of samples, notably white women; and a need to better understand the clinical implications of race and sex-specific gene-by-stress associations to the development of cardio-metabolic disease risk,” Singh said.

In addition to Singh and Williams, study authors include Michael A. Babyak, Mario Sims, Solomon K. Musani, Beverly H. Brummett, Rong Jiang, William E. Kraus, Svati H. Shah, Ilene C. Siegler and Elizabeth R. Hauser.