The herculean efforts to re-start Duke’s campus and medical school research laboratories are nearly complete.

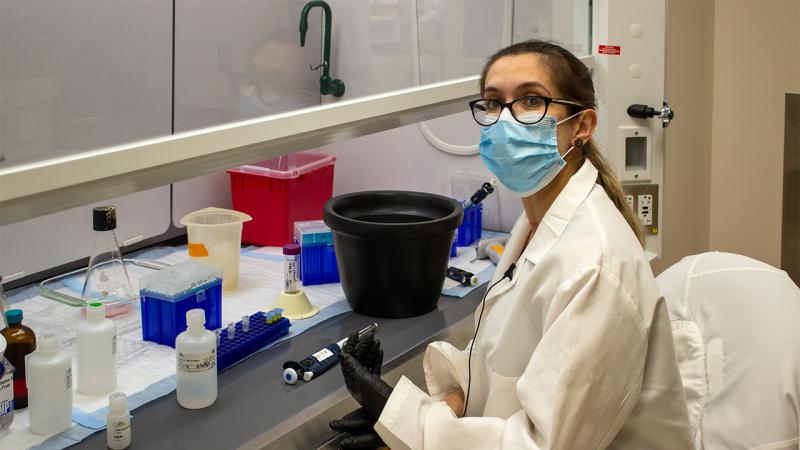

Thousands of lab workers, kept from their benches and equipment for months by the COVID pandemic, are shaking off the cobwebs and getting back to work generating data. But with some significant differences.

“I think it'll take me a few weeks to actually get back into the rhythm,” said Tatiana Segura, a professor of biomedical engineering who has a large team in two laboratory spaces in Fitzpatrick-CIEMAS.

Segura had asked all of her trainees to review their lab protocols and have a detailed plan for what they should be doing in their newly limited lab hours. But, she notes, “It takes time when you start out, like if you are trying to cook or do something you haven't done for a long time, it still takes you a while to remember how to do it.”

Each of the reopened labs has been left to decide the finer details about spacing and timing for itself, in a move campus leadership has called “state’s rights.” For many labs, that means coordinating through instant messages on Slack and a shared calendar on the cloud. Smaller rooms and shared equipment pose a particular scheduling challenge because of personal spacing requirements.

In all cases, the new safety rules mean fewer people in the lab and a highly structured end to the old free-wheeling, all-hours culture of laboratory work. Now lab workers start each day by recording their temperature and filling out a symptom survey. Their badges give them entry to buildings and elevators that used to be wide open. And they wear masks at all times. When it’s time to leave, they have to leave.

“This whole thing has been pretty challenging for us because we're used to working in teams,” said research scientist Stephen Crain, who typically works on Jungsang Kim’s quantum computing hardware with two grad students in a fourth-floor lab of the Chesterfield Building downtown. “It’s normally a pretty collaborative effort where, if we get stuck, we kind of work together. But now we're one person at a time. It's just hard to be as productive.”

As an assistant professor of chemistry and mother, Amanda Hargrove said she talks about time management with her trainees all the time. Now they’re living it. “If you're working between daycare hours, that eight hours is crazy-efficient,” she said. “So I'm a little interested to see how much more efficient people become in the four hours that they can be there.”

Hargrove has split her lab into three four-hour shifts from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. with the mandated hour for cleaning and leaving the lab between shifts. It’s all coordinated through an online calendar and Slack messaging so trainees can arrange when and how they want to work, including taking two 4-hour shifts if need be.

Third-year graduate student Martina Zafferani of Hargrove’s lab in the French Family Science Center prefers to work 10 or 12 hours at a time, much of it standing. Now she’s taking two times four hours, with an hour between to “go outside, have lunch and get some Vitamin D.”

Zafferani works in a lab that typically might hold up to 15 workers, from undergraduates to post-docs, flowing in and out during the day. On one in early June, it was just her and fifth-year grad student Sarah Wicks, wearing masks with their heads down, trying to restart their experiments on making molecules to control RNA and getting as much out of their limited time as they can.

“It hasn't been completely lonesome,” Wicks said. “But I do miss the chatter of other group members being here. We usually have about nine lab members working, we have music playing, equipment humming, and to have such silence now does make it lonelier than it was.”

Still, it’s great to be back, said first-year master’s student Ameya Chaudhari as he returned to work on bio-compatible polymers in Segura’s lab. “I had been feeling lethargic at home, but now I’m energized being back in the lab,” Chaudhari said. He looked long overdue for a haircut but was wearing one of the lab’s sharp, Duke-blue lab coats.

Duke labs that were working on questions related to COVID-19 stayed on duty throughout the shutdown, of course. And others, including Hargrove and dermatology associate professor Amanda MacLeod, are shifting some of their attention to COVID-adjacent questions as they come back.

“It’s weird being careful with everyone around,” says MSRB-III postdoctoral researcher Paula Mariottoni of MacLeod’s group. She did a sort of pausing dance to move from her bench to a tissue culture room as a colleague walked past. “Even if it’s a slow pace, moving forward is good,” Mariottoni said.

Red tape Xs mark the floors about eight feet apart in each bay of MacLeod’s MSRB-III laboratory space, indicating where people should stand to communicate or pass. The elevator is designated for one rider at a time, up only; exiting is by a designated stairway down.

Vivian Lei, MS3

Vivian Lei, MS3Third-year medical student Vivian Lei was working in the next bay over in the MacLeod group. It was designed for four, but occupied by just her. “My time during lockdown was reexamining data,” she said from behind a white cloth mask. “Weirdly enough, this was one of the most productive times in our lab.”

The timing of the shutdown in late March hit MacLeod’s group perfectly, in fact. They had just completed a move from Duke South to MSRB-III, and anticipating the move would be disruptive, the group did a lot of experiments in January and February to create a hoard of data that kept them busy.

“Our people had run a lot of the wet-lab experiments up front, and now all the analysis had to be done,” said MacLeod, an associate professor of dermatology who is studying how the skin helps combat pathogens – including viruses -- as the body’s first line of defense. During the shutdown, the lab submitted two manuscripts, three grant applications and a few fellowship applications.

Environmental toxicologist Richard DiGiulio’s lab in the Levine Science Research Center includes colorful tanks of living fish, so somebody was coming in to feed them the entire time, even though the science stopped.

“We didn't see anybody else, except for the occasional custodial worker, for 2 1/2 months,” said DiGiulio lab manager Melissa Chernick. “We just never intersected with anybody, which I thought was good because it made me feel more comfortable that nobody was in the building -- it was less possible contacts.”

Now DiGiulio, the Sally Kleberg Distinguished Professor in the Nicholas School of Environment, is waiting to hear about safety rules for field work. The lab’s supply of killifish, collected from a Superfund site on the Elizabeth River in Virginia, is beginning to wane. To get more from the river, “we all pack in a van for four hours up there and four back,” Chernick said.

The lab buildings feel different without students studying or hanging out in public areas and hallways. The coffee shops are shuttered. There are no voices, no footfalls, just whooshing air.

“It was very creepy to be alone in French,” said Zafferani, who was one of the first people back in the building. Still, it was better than working at home, she said.

“I think the beginning is going to be a little bit slower maybe than everyone hopes,” MacLeod said. “It's challenging, but it's doable.”

“And even though you have this mask on,” she said, “you can still talk and be friendly and kind to everyone.”

This article first appeared in Duke Today